Date: Wednesday, November 8, 2017

Project: Eastern Australian Waterbird Survey

Away early again. We had a bit of catching up to do, given the late start the previous day. First stop was Lake Brewster. This once natural lake is now a ‘re-regulating’ storage – a dam basically, where the water is held artificially high and stored so it can be released for irrigation and also environmental flows. Unlike many large dams, this lake has large shallow water areas which are great for waterbirds.

Surveying Lake Brewster from the south. This massive lake is used to store water but its shallow waters are productive for waterbirds.

The lake had thousands of grey teal, hundreds of wood ducks and big mobs of pelicans. It is known as one of the key sites for breeding pelicans. Last year there was a sizeable colony established on one of the levee banks used to manage the water in the lake. This year, the colony was small, perhaps no more than about 20 birds.

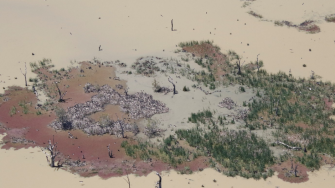

Small pelican colony on one of the levy banks on Lake Brewster.

Resting flock of pelicans on one of the levy banks on Lake Brewster

From here we headed west, towards where the Lachlan River spreads out in a delta of distributaries formed by Booligal, Merrimajeel and Merowie Creeks taking the water far out onto the floodplain.

Stunning patterns of circular irrigation systems at different stages of preparation and growth on the Lachlan River.

Last year this delta system of creeks created a massive floodplain of habitat, brimming with waterbirds and huge colonies. We headed straight for the spot where last year there were more than a hundred thousand nests of straw-necked ibis. You wouldn’t have believed it looking at it today. Just a few sheep moving in and out of the dry lignum bushes.

The pattern was the same for all of the large wetlands in this system. Where there was a bit of water, densities of waterbirds were high, capitalising on the availability of food, whether concentrated invertebrates, plants or fish. Most of the lakes and swamps of the system were dry.

The Lachlan splits into the Booligal system, which we surveyed first, and Cumbung Swamp. Once we had flown all the marked wetlands on our maps in the Booligal Creek system, checking to make sure they had no water, we headed for the Cumbung Swamp. It is a fabulous wetland, very complex with lots of different habitat types, including extenisve reed beds and river red gums.

Today, water was confined to the main channel with only a few patches of water.

The Cumbung Swamp was considerably drier than last year, with cattle and pigs concentrated around the remaining water.

The waterbirds were concentrated on scarce water in the Cumbung, mainly the channels. Last year there was so much water that we had to fly transects, north to south across the wetland but this year we could track every bit of water quite easily and get a total count of waterbirds. It was pig heaven down here. There were hundreds. Everywhere we looked there were small groups and single pigs. I have seldom seen so many pigs in a wetland.

The Cumbung Swamp and a couple of lakes to the northwest were last on our list of wetlands to survey on the Lachlan River system. Next, on to Swan Hill to refuel and survey the Kerang Lakes.

This system of lakes make up a Ramsar-listed wetland in Victoria. There are about a dozen lakes which vary considerably in their water quality and the amount they are altered by river regulation and rising salinity. Our first lake was the reasonably saline Lake Tuchewop.

Surveying Lake Tuchewop

Hundreds of banded stilts flocked on Lake Tuchewop.

Some waterbird species are ‘salt specialists’ and so it wasn’t a surprise to see red-necked avocets and Australian shelduck on Lake Tuchewop. The ‘extreme’ specialist of salt lakes are banded stilts and here we saw more banded stilts than we have seen anywhere else on our surveys over the last month and a half.

Then on to the freshwater Kerang Lakes, starting with the ‘regulated’ Kangaroo Lake. Predictably, with the artificially high water levels, these lakes don’t have many waterbirds, despite their large expanse. Sure enough – just a few pelicans and comorants and the odd black duck and swamphen.

Surveying the shoreline of Kangaroo Lake with its residences. This permanent water lake seldom has any waterbirds, apart from a handful of fish-eating birds.

Once done here, we headed west a few kilometres to the Bael Bael system of lakes, also part of Kerang Lakes. The contrast with the other lakes could not have been greater. These lakes seem to be able to flood and dry naturally. Straight away we saw the aquatic plants growing in the clear shallow water. We were busy. Clouds of grey teal rose up in front of the plane while there were also hundreds of tightly clumped coot in the middle of the lakes. But not only that, these lakes had a very high diversity of waterbird species. It was also great to see blue-billed ducks. We don’t often see them because they dive when the plane disturbs them.

Surveying the Bael Bael system of lakes with tens of thousands of waterbirds; bugs on the lens reflected the high productivity of the lakes.

From here there were a few more freshwater lakes, with predictably few waterbirds. Middle Lake is one of a string of three of the more eastern freshwater lakes. This one is always interesting because it is a key lake for breeding waterbirds, particularly straw-necked ibis and Australian white ibis. There was an impressive colony of more than a thousand straw-necked ibis; most of the chicks looked almost fledged. There was also a small colony of royal spoonbills.

Part of a large colony of straw-necked ibis, Australian white ibis and royal spoonbills on Middle Lake of the Kerang Lakes in Victoria.

Last year, our honours student Emily Webster, put some GPS transmitters on straw-necked and Australian white ibis. And one of her straw-necked ibis, caught in the Barmah-Millewa Forest ended up nesting here on Middle Lake and foraging on the river to the north. This colony is one of the most dependable in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Once the lakes were done – we were finished for the day. Our plane was spattered with dead insects a clear confirmation of the productivity of the Bael Bael lakes. Tomorrow we would head home to Sydney, with just one leg remaining next week in the north of the Murray-Darling Basin.