What is happening with religious discrimination laws in Australia?

2024-03-26T11:02:00+11:00

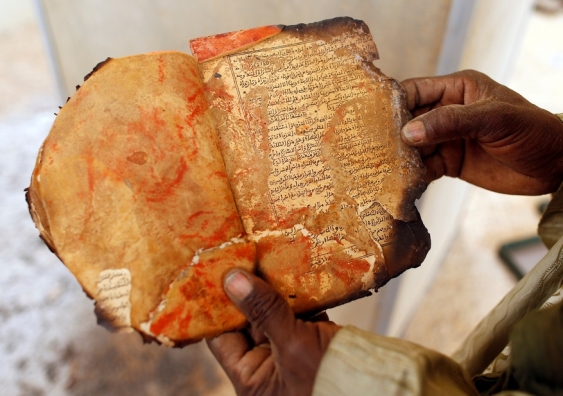

Photo: Getty Images

A UNSW law academic explains a major new report and its implications for different communities.

On 21 March 2024, the Australian Federal Government released a December 2023 report from the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) on religious educational institutions and anti-discrimination laws. The release of this report aligns with signals from the federal government that it intends to fulfill one of its election promises: to attempt to legislate on the protection of religious freedoms in Australia.

In this explainer, Professor Lucas Lixinski, Associate Dean (International) at UNSW Sydney’s Faculty of Law & Justice and an Associate of the Australian Human Rights Institute at UNSW, discusses the new report and its implications for communities of faith and LGBTIQ+ individuals and communities.

What does the Australian Law Reform Commission recommend in its report on religious discrimination?

In its report, the ALRC recommends that the federal Sex Discrimination Act 1984 be revised to explicitly forbid religious educational institutions from discriminating on the basis of “sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status, or pregnancy” against teachers, all other workers, and students and their parents. It also recommends allowing religious institutions to indirectly discriminate (as long as reasonable) to accommodate the special needs of these institutions, as well as protecting the ability of religious educational institutions to train religious leaders in a way that abides by the requirements of their faiths.

The protection of indirect discrimination is important here. It preserves the rights of religious institutions in many respects that they considered most important in their submissions to the ALRC, but it shifts the burden of defending those rights. Instead of these rights existing and it being upon an LGBTIQ+ person to have to prove the overwhelming individual and social harm of certain exercises of these rights, now it is on religious organisations to justify the exercise of these rights when they have negative impacts on people. Since religious organisations nearly always have more resources than individuals, it makes sense that institutions carry this type of burden in these asymmetrical relationships.

The report also recommends that the Fair Work Act 2009 be amended to specify that religious institutions can still prefer persons of faith in their hiring decisions so as to help in building and maintaining “communities of faith”, but that they cannot use those preferences to disguise discrimination. This exception only applies to hiring, it cannot be used to hold people back in promotion, or to fire people. The recommendation outlines a proportionality test to make sure this exception is used well.

The ALRC made all these recommendations considering some important principles. The key principle is that all human rights are indivisible and interdependent. So, it does not make sense to protect one right at the expense of all others. Rights need to be balanced, in the words of the ALRC, to promote human flourishing.

Will the ALRC’s recommendations be implemented? What has the federal government committed to doing on the issue?

The government is not obligated to follow the ALRC’s recommendations, but they carry a lot of weight. To date, the government has said it wants to legislate on this matter, alongside legislating on religious freedom more broadly. Even though it probably has the numbers to pass the legislation with the crossbench, it is seeking bipartisan support to avoid the type of divisive and poisonous public debate we have had most recently with the Voice referendum, and a few years ago with the same-sex marriage postal survey.

This could mean a delay in reform, but it also protects those most likely to be victimised by a binary “government v opposition” public debate, which risks pitting Australians against one another.

Why do religious organisations want the right to discriminate on the basis of sexuality and gender identity within their own institutions?

Religious organisations reiterated again and again in the ALRC process that these discriminations are important to protect the tenets of their respective faiths. Most of these organisations rely on readings of their religious teachings that focus on a world where LGBTIQ+ people have always existed but were largely invisible. Religions, much like other forms of social organisation, often rely on creating an “us” and a “them” to bring people together under their umbrellas. LGBTIQ+ people have often been an easy “them”, and many religions have at one point or another condemned them for being sinful, and therefore dangerous, because they did not fit into the society these religions wanted to create.

When they expanded their power, however, religious organisations also started getting closer to the state, and forged alliances to guarantee funding and power by offering services that were otherwise the duty of the state (like education and an array of social services). As the state cannot discriminate in the same way, religious organisations that rely on state funding need to be more inclusive, and they often resist those mandates.

What legal protections are LGBTIQ+ organisations hoping to see from the government alongside these proposed reforms?

LGBTIQ+ organisations around the country have supported the ALRC report, and urged the government to adopt it in full. The next natural step is to extend these norms to all other religious service providers.

Much of social service provision (in health, aged care, and many others) depends on religious organisations in Australia. It is still sadly a common phenomenon for LGBTIQ+ people to re-closet themselves (and sometimes even de-transition) when they need to move into residential aged care facilities run by religious organisations. In certain parts of the country, especially rural areas, people do not have a wide range of choice in service providers, so this type of discrimination, using public funding, cannot stand.

Further to the extension of these anti-discrimination rules, one possible next goal is to see Australia adopt a broad federal Human Rights Act. Australia remains one of the few countries in the world that does not have comprehensive human rights protections at the national level, only sparse and right-specific legislation. Comprehensive legislation would appropriately recognise the interdependence of human rights, and how all rights need to come together for everyone.

Christian Schools Australia says the expulsion of LGBTIQ+ students "doesn't happen, never has and we don't want it to". Is that true? Why are these exemptions then necessary?

It might be true that LGBTIQ+ students are not expelled. But they may be threatened with expulsion, or at least schools have in the past (and in recent memory) used these loopholes to create environments that are not welcoming of LGBTIQ+ students or staff.

The ALRC recalled these incidents and used them to good effect. They found that, even if not an actuality, just the possibility of this type of discrimination already creates an unjustifiable social harm because of the symbolic role of these rules in signalling what is or is not acceptable in the community. If it is the case that schools do not engage in discriminatory practices, as many indicated to the ALRC, the ALRC responded that then it should not be a problem for this type of reform to be adopted.

Media enquiries

Drew Sheldrick, Communications Manager, Australian Human Rights Institute

Tel: 0421 012 114

Email: d.sheldrick@unsw.edu.au