OPINION: In the first of its kind, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has delivered an important judgment on the destruction of World Heritage.

International law clearly protects cultural heritage from attack, including during armed conflict. But such crimes are seldom prosecuted and tend to be viewed as secondary to crimes against people. The ICC has partly changed this in the case against Ahmad Al Faqi Al-Mahdi, a local leader in Timbuktu who was appointed as head of the morality police when power changed hands in the city. The case exclusively concerned attacks against cultural heritage.

This is the first ICC case to examine attacks against cultural heritage. It is also the first to consider the actions of terrorist movements linked to Al-Qaeda. Its findings are likely to affect how the international community responds to attacks on cultural heritage – for example, the destruction of Palmyra in Syria by Islamic State.

The judgment sends the message that the international community will not tolerate destruction of cultural heritage sites. That is to be welcomed. But in our view the judgment did not go far enough. This is because it also sends the message that the court values the culture that binds a community together less than the toll on human lives. While understandable, we suggest that the court’s reasoning is shortsighted and that it missed a valuable opportunity.

We would argue that protecting cultural heritage sites is equally important and connected to the protection of civilian populations. After all, as the ICC recognised in its judgment, the heritage site was a large part of the social glue that made the individuals living in Timbuktu a community.

Without culture, people are but an assembly of organisms in the same species. Culture makes us a people, a civilisation.

Cultural heritage in times of war

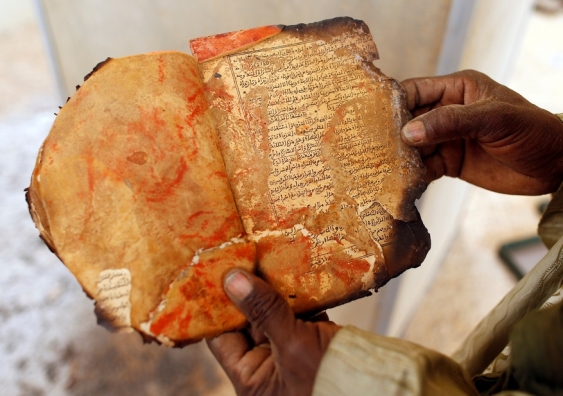

The rise of the so-called Islamic State (Isis) in recent years has seen a spike in attacks on and destruction of globally significant sites of cultural heritage. Some of these have included Palmyra and Aleppo in Syria, the Shrine of Jonah in Iraq and Timbuktu in Mali, which date back centuries and were internationally recognised as protected sites.

Increasingly, such sites are targeted precisely because of their religious and cultural significance and their value to the international community.

The ancient city of Timbuktu holds a special place in Islamic and world history. It played an essential role in the spread of Islam in Africa during the religion’s early period. Its mosques also made it a commercial, spiritual and cultural centre in the trans-Saharan trading route.

Following the collapse of government in Mali in 2012, terror groups occupied the power vacuum. These groups include:

MUJWA, an offshoot of Maghreb Al-Qaeda;

MNLA, Tuareg nationalists;

Ansar Dine, Muslim fundamentalists who ordered the destruction of Timbuktu escalating the activities of the morality police led by Al-Mahdi; and

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, a franchise of Al-Qaeda that runs separately from the Saudi Al Qaeda. It was responsible for the 9/11 attacks in the US.

Al-Mahdi was an educated and respected member of the local community in Timbuktu. From April 2012 he was the head of the Hesbah, the morality brigade responsible for enforcing the religious and political edicts of the two terrorist groups, Ansar Dine and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The two groups had gained control of Timbuktu. These organisations decided that the mausoleums to the saints and the mosques in Timbuktu were to be destroyed.

Al-Mahdi initially advised against their destruction, recognising that the sites were an important part of the community’s religious and cultural life.

But the ICC found that in organising and providing the means for the destruction and participating in the destruction of five sites, Al-Mahdi was criminally responsible for total or partial destruction of 10 of the most significant sites in Timbuktu. These included several parts of the World Heritage Site.

Heritage versus human lives

The ICC sentenced Al-Mahdi to nine years imprisonment, which was within the range of nine to 11 years agreed by the prosecution and defence. The sentence recognised the gravity of the crime, the significance of the cultural heritage destroyed and the religious motivation for its destruction.

But the judges also highlighted that the destruction of “property” – no matter how culturally significant – is less grave than crimes committed against individuals. In other words, cultural heritage has been relegated to a subset of property offences.

In doing so, the ICC suggests that destroying a cultural heritage site that has stood for centuries, and is an important part of a group’s social glue, is about as bad as destroying a modern hospital. While both buildings play important roles, one is much harder to replace than the other. The ICC does not seem to have taken that fully into account.

This will have repercussions for the future protection of cultural heritage in armed conflict.

The judgment also ignored the connection between acts against cultural heritage and violence against the civilian population, which are often both justified by the same discriminatory religious ideals. This therefore weakens its potential to send a strong signal that intentional destruction of cultural heritage will not be tolerated.

The international community has always been reluctant to acknowledge this reality and turn it into law. There are other historical examples.

During World War II, and in many conflicts since, this realisation was always in the mind of the major war criminals, as witnessed in the Nazi policy of destroying Jewish art; the bombing of Dubrovnik during the Yugoslav wars; and the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan.

The ICC had the chance to change the world’s approach to these acts. But it fell short.

Identifying victims of cultural loss

Al-Mahdi accepted responsibility and demonstrated remorse for his actions. He pleaded guilty at an early stage and cooperated with the prosecution. Other possible defendants may have taken note of the court’s recognition of this in his sentence.

His guilty plea certainly saved valuable time and resources. And the case has been the most efficient and speedy ICC trial to date. This is an important win for an institution that has struggled to deliver timely justice and faces serious challenges to its credibility due to the collapse of key trials.

The conviction also opens the door for the ICC to consider suitable reparations to victims for the destruction of the sites. This will be the first time an international court has had to consider how one compensates for the loss of the irreplaceable.

Eight victims participated in the trial process. But the court will have to explore who the victims of destruction of cultural heritage are: individuals, local communities, the state of Mali or the international community?

The ICC prosecutor, and the court itself, recognised that at some level all are victims. Indeed, while the suffering of the local community in Timbuktu is deepest of all, we are all affected by the loss of the treasures that bind us as humankind.

If only the ICC could fully see that.

Lucas Lixinski is a Senior lecturer in Law at UNSW.

Sarah Williams is an Associate Professor in Law at UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation, opens in a new window.