Impact of our donors

Momentum for constitutional recognition of Australia’s First Nations peoples is growing, supported by the leadership of Professor Megan Davis, a game-changing gift from the Balnaves Foundation, and the abundant grace of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across the country.

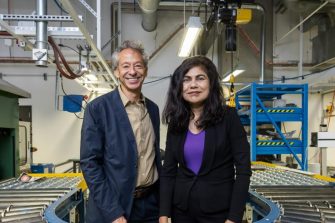

In May 2020, on the third anniversary of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, in the first anxious months of the pandemic, long-time UNSW Sydney partner, the Balnaves Foundation, announced a gift that would lend considerable momentum to the push for a First Nations Voice to Parliament, enshrined in the Australian Constitution. The gift of $1.25 million enabled UNSW to establish the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law, a role that would be filled by Megan Davis, Professor of Law and Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous at UNSW.

Hamish Balnaves, CEO of the Balnaves Foundation, recalls that all those involved were determined to push ahead with the announcement, despite the distractions of the pandemic. The feeling was that there was no time to be lost.

“I believe in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the need for a voice, the need for truth-telling, the need for treaty,” he says. “We’re way behind where we should be, and the injustice of it only compounds over time.”

That sense of urgency is shared by many. It’s now four years since the Uluru Statement was first shared, but many years more since constitutional recognition for First Nations peoples was first discussed at a political level.

An excerpt from the Uluru Statement from the Heart

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs.

This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors.

This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

In 2015, Megan was one of 40 Indigenous leaders invited to Kirribilli House to meet with the leaders of the major political parties for a discussion about a referendum on the issue of constitutional recognition. The Indigenous leaders, wary of a merely symbolic interpretation of ‘recognition’, raised the need for a new and ongoing dialogue to negotiate the terms for a referendum.

Megan was one of 16 people appointed to the new Referendum Council. In the months that followed, the Council held meetings across the country, enabling Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to hear and debate the five proposed models for constitutional reform. As a constitutional lawyer, Megan was responsible for designing and rolling out these deliberative ‘dialogues’. The process was inclusive, exhaustive and momentous.

Alexandra Balnaves, daughter of Foundation founders Diane and Neil, and sister to Hamish and Victoria, was a strong supporter of Megan and her work on constitutional recognition dating back to the early 2000s.

“Alexandra deeply understood the potential for structural reform and was a great source of professional strength,” says Megan. “The dialogues process was a blur in some ways. It was the most intense time in my life, and all-consuming as such serious law reform work must be."

The dialogues culminated in the First Nations Convention at Uluru in May 2017, with the historic pronouncement of the Uluru Statement, calling for a First Nations Voice to be enshrined in the Constitution, and for a newly formed Makarrata Commission to supervise the processes of treaty and truth-telling between governments and First Nations people.

Since then, supporters have continued to advocate and campaign for the reforms set out in the Uluru Statement. Led by Megan and the UNSW Indigenous Law Centre, they have also pushed forward with the underlying scholarly work required to drive the necessary constitutional and legislative changes.

In 2019, Megan’s friend and ally, Alexandra, passed away. Inspired by her lifelong dedication to Indigenous education, the Balnaves family made the decision to honour Alexandra’s passing with the gift that would support Megan’s work and help make the aspirations of the Uluru Statement a reality.

“I really do believe in my lifetime we will see real, tangible change. But things aren’t going to change without an Indigenous voice being empowered at the highest level. Without that, you just can't have meaningful reconciliation,” says Hamish.

The Balnaves Foundation’s history with UNSW goes back more than a decade. The family has supported multiple scholarships for Indigenous students undertaking degrees with UNSW Law, and funded the development of Balnaves Place, the home of Nura Gili, UNSW’s Centre for Indigenous Programs. These initiatives are part of a wider program of Indigenous support from the Foundation, including funding for the Bangarra Dance Theatre in Sydney, and for the Indigenous Affairs Editor of The Guardian.

“Philanthropy plays a key role in supporting causes and reforms that no one else will. It requires prescience and vision. And that’s why the Balnaves are so important: they can see something that others can’t see,” observes Megan. “The added advantage of philanthropy is that you get to know people. It’s relational, and so it’s not as remote and clinical as it can be within government sectors.”

The success of their previous partnerships with UNSW gave the Balnaves family every reason to feel confident about this latest venture with the University, says Hamish. Nonetheless, the family wanted it to be known that they expected Megan to be outspoken in her role as the Balnaves Chair.

“The work she's done in the legal space for Indigenous people and the policies that affect them isn't that well known,” he says. “But making the Uluru Statement happen, and getting a broad consensus behind it, that was no easy feat.

“She's got the drive and the toughness to deal with the politicians and with the opposition that she will inevitably face. She's got the strength of character to be able to battle through that. She's an impressive individual. We’re backing the right person.”

Says Megan: “The Balnaves family are really important to me. They’ve backed my research, and all the work and thinking that went into the Uluru Statement. Now they’re funding me to deliver on it. Their confidence in me and their belief in the vision of the Uluru Statement is what helps me keep the faith.”

As a young law graduate, Megan began working with the Foundation for Aboriginal Islander Research Action (FAIRA). She helped organise community workshops on the repatriation of human remains, wrote legal analyses on native title decisions, and contributed to stolen wages litigation.

Her career as a constitutional lawyer and advocate for global Indigenous rights was given a nudge when she won a United Nations (UN) fellowship.

To this day, she serves as an expert and Vice-Chair of the UN Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Informed by those experiences, Megan was instrumental in allowing the Referendum Council dialogues to serve as a forum for the resolution of tensions, agreements and disagreements between the many voices invested in the idea of constitutional recognition. The ultimate reward was a powerful consensus built on the strength, the conviction, and the heart of all those involved.

“The greatest lesson I learned from the dialogues was the generosity of spirit of our old people, and their pragmatism. They turned up to the meetings with energy, and they brought the cultural protocol, and the allegories, and the leadership,” says Megan. “They led with the language of peace and friendship.”

There is a grace, a warmth and a sense of welcome in the text of the Uluru Statement that some might find surprising; an invitation to "walk with us" that comes not from what might be regarded as the sources of power, but from those who have suffered the injustice of powerlessness. It reminds us that recognition and truth-telling will produce a “fuller expression of Australian nationhood” and that the embrace of First Nations peoples and their culture will be “a gift” to the country. It promises that voice, treaty and truth will deliver us “a better future”.

“Resolving this is a moral imperative, essential for modern Australia’s story, and essential for our identity as a nation,” says Hamish. “The injustices that have occurred since British settlement of our country are shocking and uncomfortable. They are a dark stain on our history. Ultimately they can only be resolved and dealt with through a process of treaty making, but I will feel better as an Australian when we have dealt with it and recognised it," says Hamish.

“It is fantastic to be connected to this, to meet people like Megan, and to be involved in a small way in helping them with their work. The opportunity to be part of it, and to fund it, is really exciting.”

Images: Richard Freeman and Simon Bradfield

Words: Julia Richardson

Share this story