Global guidelines for sustainable exploration could help preserve celestial environments.

The Grand Canyon, the Great Pyramids of Giza and other places of natural and cultural heritage on Earth are protected by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. But what about space?

How we identify and preserve valuable celestial environments while also exploring them is known as the environmentalist’s paradox, says Clare Fletcher, a geoconservationist and PhD candidate at UNSW Science’s Australian Centre for Astrobiology.

“The minute and fragile nature of early life sites means evidence could be inadvertently and irrevocably damaged during exploration, preventing its further study,” Mx Fletcher says.

“Exploration is necessary for us to better understand space, but if it causes damage, it can hinder that understanding. Evidence of life typically occurs on a small scale.”

Media enquiries

For enquiries about this story and to arrange interviews, please contact Isabelle Dubach.

Tel: + 61 432 307 244

Email: i.dubach@unsw.edu.au

Mx Fletcher says space exploration needs to focus on its sustainability earlier rather than later.

“If you don't think about the longevity early, you end up destroying things for the future.

“Some of the oldest-known evidence of life on Earth has been destroyed, sometimes in the name of science,” they say. The site of Dunlop, discovered in the remote Pilbara region in Western Australia in 1980, no longer exists due to excessive geological sampling.

“We’ve lost the story of its broader environmental context and what that can tell us about the conditions for early life.”

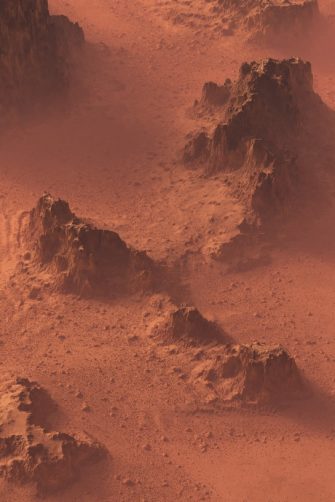

Mx Fletcher is examining how we approach geoconservation – the preservation of valuable rocks, soils, landforms, including potential evidence of early life – on Mars by engaging in more sustainable space exploration.

“Of all the planets in our solar system, Mars is most likely to have evidence of life. The present legal regime will not protect its ‘outstanding universal geoheritage value’, to borrow the World Heritage terminology for space,” they say.

The current frameworks – the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) Planetary Protection Policy (opt-in guidelines) and the Artemis Accords (bilateral agreements) – are concerned with preventing microbe contamination and promoting peaceful, responsible global cooperation respectively.

While these are important concerns, they do not address the protection of planetary geology, landscapes or potential ancient evidence of life, they say.

Of all the planets in our solar system, Mars is most likely to have evidence of life. The present legal regime will not protect its ‘outstanding universal geoheritage value’, to borrow the World Heritage terminology for space.

Global guidelines will encourage more sustainable practices

Mx Fletcher is researching how we might determine if a site on Mars has geoheritage value and how human exploration can affect this. They are developing best-practice guidelines as well as pursuing legal and policy reform to promote the planet’s continued study and exploration.

The race to send the first crewed mission to Mars is on. The planet's proximity and potential evidence of life make it attractive for exploration, even colonisation, they say.

“While no life on Mars has been found, we have found interesting samples in paleoenvironments [geological environments preserved in rock] similar to those on Earth [three and a half billion years ago] that we believe were the precursors for life,” they say.

“This is significant when we’re considering Mars exploration because we believe Mars was experiencing a warm and wet period [at this time] so potentially … it was habitable and therefore could have evidence of life.”

In 2004, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Mars Exploration Rover Spirit found digitates, minute finger-like structures, comparable in shape and structure to digitates alive in hot springs on Earth.

“This is significant because we think that shape might only be caused with the presence of microorganisms [essential to life on Earth]. Studies are still being done to prove this,” they say.

“Also, the oldest, convincing evidence of life on Earth in the Pilbara is in a hot spring paleoenvironment.”

This site, the Columbia Hills Home Plate, is just 80 metres in diameter. Routine space exploration could damage such sites, with adverse events causing considerably more harm, Mx Fletcher says.

In 2023, SpaceX conducted a test launch of its rocket starship. “It blew a giant crater in the launchpad throwing chunks of concrete and debris … [across an area] one kilometre in diameter,” they say.

“There were dust and particulates over a ten-kilometre diameter. That area of significant damage is 156 times the size of Home Plate.” Heat and debris emitted during the landing process could also cause damage.

Mx Fletcher has presented to the United Nations (UN) Legal Subcommittee of the UN Committee of the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space promoting proactive science-led policy to reduce the risk of damaging valuable celestial sites. But policy change takes time, they say.

In the meantime, science and technology continue to advance. Cuts to global governments’ space exploration budgets – for example, NASA’s budget has dropped to $US24 billion in 2024 from a peak of $US6b in 1964 – mean that Mars exploration is being progressed in many cases by non-state actors, such as SpaceX and Boeing.

Mx Fletcher is engaging with global space sector professionals and academics to identify best-practice guidelines for sustainable exploration. The success of COSPAR’s Planetary Protection Policy demonstrates the potential positive impact of voluntary guidelines created by and for the space sector, they say.

“These will help us proactively plan, strengthen the legal regime, enhance international cooperation and expand our ability to explore more sustainably.”

Rehearsing Martian life and research on Earth

Examining ancient environments on Earth can help us to better understand Mars, its evolution and its history, Mx Fletcher says.

Earlier this year, they lived and worked as an astronaut for four weeks at the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah, USA as part of two international research crews. They were investigating how adjusting practices in the space analogue facility could mitigate human impacts on ancient environments.

The remote station, owned and operated by the Mars Society, simulates the physical and psychosocial aspects of missions to Mars in a location with geological affinities to the red planet.

The rock record has stayed intact for up to 161 million years and has similar geology and paleoenvironments to Mars, Mx Fletcher says. Researchers suit up and embark on extra-vehicular activities (EVAs) into the surrounding terrain. “In this testing ground, scientists and engineers can hone their skills for identifying signs of life.”

Crews of up to seven eat, sleep and work in the station’s cylindrical habitat, “a glorified tin can” just eight metres in diameter. This is connected to a science dome (a lab space), a climate-controlled greenhouse for growing fresh vegetables, and an observatory by narrow tunnels enabling crews to move between facilities without breaking the simulation.

During the missions, Mx Fletcher engaged with equipment and techniques that will be used to analyse the surface of Mars, conducting geological fieldwork and data analysis. The experience highlighted some of the practical challenges for identifying sustainable exploration guidelines.

For example, pre-mission remote sensing could not be relied upon for decision-making around conservation, they say. “I had a lot of issues identifying targets that I was looking for [in the landscape] … The remote sensing data, all the work that gets done beforehand, did not match what it’s like on the ground.”

Their experience in the Utah desert reflected issues with locating remote sensing targets reported during NASA’s Mars missions. Reduced visibility in the spacesuit also hampered on-the-spot decision-making about whether to sample.

In space, visibility is further mediated through technology. “Rover cameras, even [NASA’s] Ingenuity helicopter is limited in its perspectives,” Mx Fletcher says. Identifying when in the mission and how decisions around conservation are made will feature in their sector engagement.

While missions at the remote station last weeks rather than months and the habitats and spacesuits aren’t pressurised, the facility allows us to rehearse life on Mars. Whether that’s the first crewed mission or its colonisation, only time will tell.

“We don’t know what else is out there on Mars. And we won’t know unless we explore,” Mx Fletcher says. “Asking how we can conserve sites that may contain key stories of its evolution is central to advancing our understanding.”