Each year, millions of Muslims from across the world embark on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. The mass migration is unparalleled in scale, and pilgrims face numerous health hazards.

Mecca is considered the holiest city for Muslims. And Hajj is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, making it a mandatory religious duty for Muslims to perform at least once in their lifetime if they are physically and financially capable.

The 2024 Hajj pilgrimage has been overshadowed by disaster/tragedy, with the death of at least 900 pilgrims, mostly due to heat exhaustion and related complications.

This isn’t the first deadly disaster during Hajj

One of the most devastating incidents occurred in 2015 during the ritual of “Rami al-Jamarat” in Mina, near Mecca. This ritual involves pilgrims throwing stones at pillars symbolising the devil. On that day, overcrowding and the movement of large groups of pilgrims in opposite directions led to a deadly crowd crush. More than 2,400 pilgrims lost their lives, making it one of the deadliest disasters in the history of Hajj or any mass gathering.

Another mass casualty event occurred in 1990, in the Al-Ma'aisem pedestrian tunnel near Mecca, which led to the holy sites. A combination of ventilation failure and an enormous influx of pilgrims caused a suffocating crush inside the tunnel; 1,426 pilgrims died.

There have also been other incidents during the Hajj pilgrimage over the years. In 1994, a stampede near the Jamarat Bridge resulted in the deaths of around 270 pilgrims. The 1998 Hajj saw 118 pilgrims killed in another stampede.

Over the past half-century, more than 9,000 people have died in mass religious gatherings, with more than 5,000 of these occurring during the Hajj in Saudi Arabia. India follows with at least 2,200 deaths across nearly 40 tragic events. These two countries are hotspots for such tragedies.

Why is the Hajj pilgrimage so risky?

With millions of pilgrims converging in a confined area, the potential for overcrowding and crowd-crush accidents is high. This situation is worsened by the high emotion and passion associated with the pilgrimage. Pilgrims perform rituals with intense devotion and enthusiasm, which can sometimes lead to overexertion.

Another factor is the age of the pilgrims. Many are elderly, having saved for years to afford this spiritual journey. Their advanced age makes them particularly vulnerable to the harsh conditions and physical demands of the pilgrimage. The intense heat, prolonged periods of walking, and sheer physical strain of performing the rituals can exacerbate existing health issues and lead to new complications.

The extreme congestion of people also amplifies health risks, particularly from infectious diseases. Communicable diseases such as SARS, avian influenza and meningococcal disease have posed significant threats during Hajj in the past.

High temperatures make mass gatherings riskier

A study documenting deaths and injuries at mass gatherings up to 2019 shows that, while the 1980s saw most fatalities at sporting events, such events are now rare, while fatalities during religious pilgrimages, particularly in India and Saudi Arabia, are becoming more common.

While most Hajj fatalities have been due to crowd crushes and stampedes, a new threat has emerged: extreme climate. Saudi Arabia’s climate can be brutal. During this year’s pilgrimage, temperatures soared to 50°C.

Saudi Arabia is warming at a rate 50% higher than the rest of the Northern Hemisphere. The decade from 2010 to 2019 was the warmest on record, with more frequent and severe heatwaves. This rising temperature, combined with higher humidity, makes conditions increasingly unbearable without artificial cooling.

The timing of the Hajj pilgrimage, dictated by the lunar Islamic calendar, means it shifts approximately 10 to 11 days earlier each year in the Gregorian calendar. This means Hajj can occur in different seasons over a 33-year cycle. Currently, Hajj is being held during the summer months, leading to extreme heat risks.

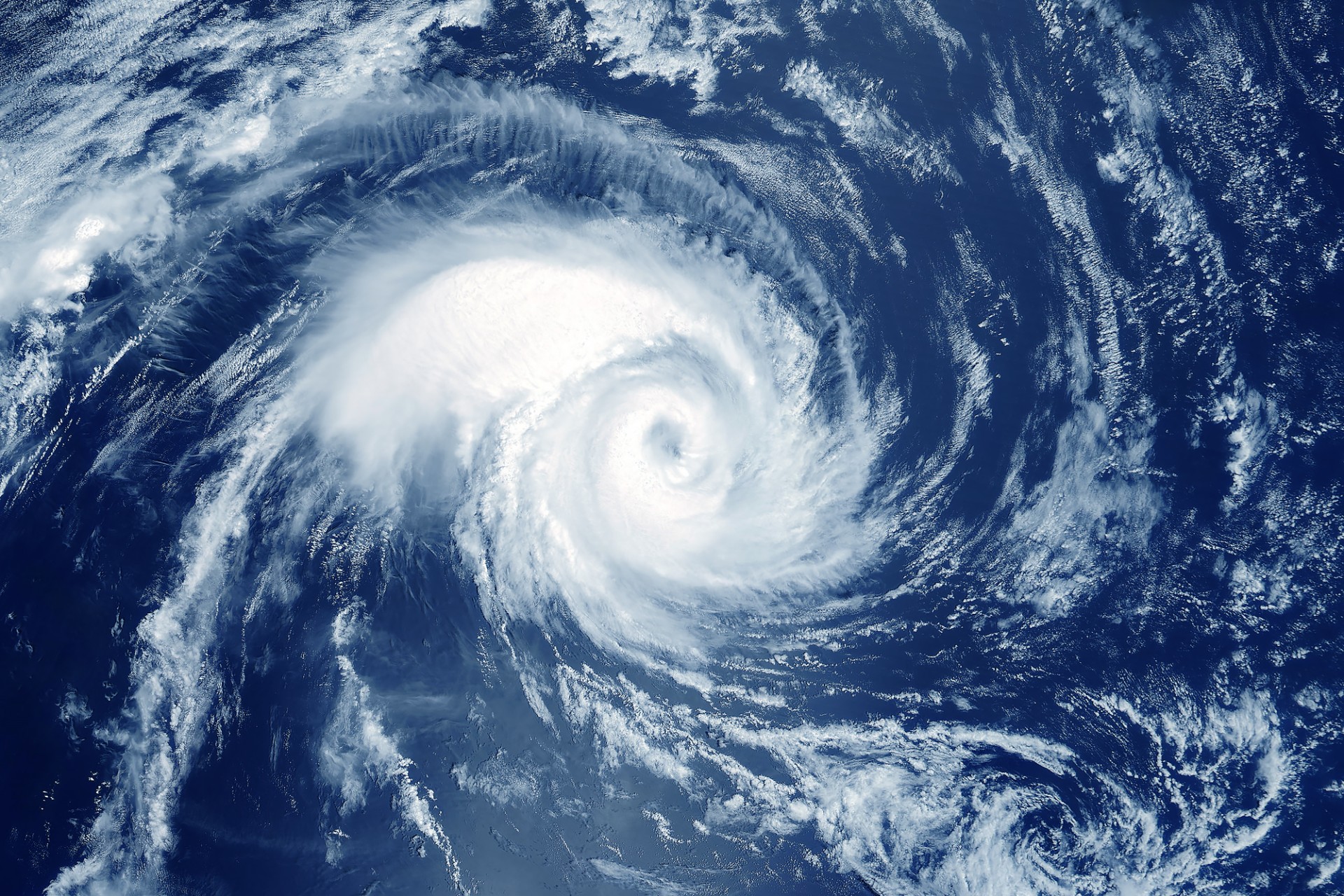

Saudi Arabia has also experienced an increase in extreme rainfall events in recent years, particularly towards the end of summer and into the fall. These torrential downpours and thunderstorms have caused significant flooding in regions such as Mecca and Jeddah.

As climate patterns continue to evolve, the occurrence of such rainfall could align with the Hajj season, creating additional hazards for pilgrims.

What can be done to mitigate the risks?

Unlike concerts or sporting events, the Hajj pilgrimage cannot be rescheduled or relocated. Being outdoors is an integral part of Hajj.

It’s crucial for pilgrims to perform the Hajj rituals correctly for their pilgrimage to be accepted. According to Islamic teachings, the Hajj must be conducted with precise adherence to its rituals and timings. Any deviation or omission can render the pilgrimage invalid.

The Saudi Ministry of Health has implemented various measures, including encouraging vaccinations, health checks and educational campaigns urging pilgrims to stay hydrated, use umbrellas and avoid prolonged sun exposure.

The ministry deployed thousands of paramedics and set up field hospitals to manage the crisis. Cooling measures such as misting systems and portable water stations were used.

Yet the extreme heat proved overwhelming, indicating more needs to be done.

Educational campaigns can do more to raise awareness among (especially non-local) pilgrims and health-care workers about heat risks and preventive measures.

The introduction of new technologies such as smart bracelets for monitoring pilgrims’ health could further enhance medical responses.

Milad Haghani, Senior Lecturer of Urban Mobility, Public Safety & Disaster Risk, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.