Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has declared a “national crisis” of domestic violence following an alarming spike in killings of women and a wave of protest rallies across the country. A dedicated meeting of National Cabinet has pledged $925 million to tackle the problem, including permanently funding the Leaving Violence program, which provides up to $5,000 crisis support to eligible women.

This is not the first time domestic violence has been declared a national crisis, or that governments have promised increased funding to deal with it. For some, it feels like Groundhog Day: here we go again. Knowing how often we have been here before can help us build on what has been proven to work and learn from past mistakes. But what can history tell us?

We are researching the history of domestic violence in Australia. For us, the importance of knowing this history was highlighted by a recent conference marking the opening of Australia’s first feminist refuge, Elsie, 50 years ago – on March 16, 1974. It was convened by Anne Summers, one of the six women who started Elsie. Most delegates work in, or have worked in, the domestic and family violence sector, among them victim-survivors.

The mood of the conference, where 50 “unsung heroines” of the feminist refuge movement were honoured, was equal parts celebratory and weary. After 50 years of activism, there was palpable despair that domestic violence is not only still rife, but has taken on new, insidious forms like technology-assisted abuse. Throughout the country, to varying extents, successive neoliberal governments have kept front-line services in a perpetual cycle of funding uncertainty.

The sector’s struggle to be properly resourced continues. For example, a Blacktown migrant women’s refuge is turning away five to six women a week. It receives no government funding, even though it gets referrals from government services.

We have seen 50 years of countless dedicated conferences, action plans, reports, inquiries and proposed solutions for reducing and eradicating domestic and family violence. At their best, these initiatives yield tangible results. Recently, the Victorian government accepted all 227 recommendations from the Royal Commission into Family Violence in Victoria – and invested record funding.

In 1997, the Howard government de-gendered the language of domestic violence (which is overwhelmingly committed by men against women) to fit his “family values” approach and replaced former Prime Minister Paul Keating’s plan to address it with his own. But governments since have taken a more bipartisan approach, and strategies developed by one side of politics have at times been taken over by the other. After his election in 2007, Kevin Rudd reintroduced the language of “violence against women” and this approach has survived subsequent changes of government.

In practical terms, support services have been expanded and police attention has increased, as has the sharing of knowledge between different agencies supporting victims. Despite these gains, so many women are seeking help that support agencies can barely keep up. National Legal Aid recently reported that in New South Wales alone, there was an increase of 61% in duty services provided by the domestic violence unit and a 36% increase in calls to the unit’s hotline.

The first national conference: 1985

When, how and why did domestic violence become a government concern in the first place? And what has happened since?

Our story starts in November 1985, with the first government-initiated national conference on domestic violence. At this point, more than a decade of feminist activism on the issue had seen the establishment of relevant agencies by successive state governments, starting with New South Wales. Some forms of domestic violence were criminalised across the states and territories, including long-standing assault laws and apprehended violence orders in New South Wales that had been introduced three years earlier. But they were inadequately policed and prosecuted.

The attorney general, Lionel Bowen, asked the Australian Institute for Criminology to host a conference, to provide the government with advice. He put the need to improve family law and policing – which remain works in progress – on the agenda. The organisers particularly identified the need for resources for ethnic groups and First Nations women, about whom knowledge was relatively scarce.

Over five days, more than 300 participants listened to the testimonies of survivors and support workers, representatives of various church and migrant community organisations, and researchers’ findings.

Consensus would not be easy. Even the term “domestic violence” was disputed. Some were concerned its neutrality avoided the criticism of marriage contained in “wife bashing”. But most speakers referred to “domestic violence”: the term had already taken root.

Feminist contributors wanted to have domestic violence considered and treated as a crime. They urged the criminal justice agencies to take women’s testimonies more seriously but also noted that a fixation on legal responses could obscure the need for continuing support for community services. They saw achieving gender equity as essential for long-term solutions.

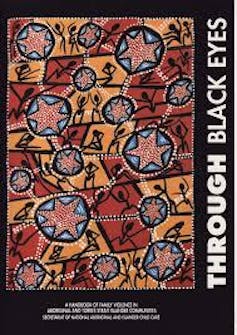

Various proposals were made at the conference. The extensive recommendations covered policy, funding, research, housing, childcare and education. These were a guide for subsequent initiatives, such as a report commissioned by the Office of the Status of Women on Aboriginal women’s issues in 1986, and the 1991 publication of Through Black Eyes: a handbook of family violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities by the Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Childcare Agencies.

However, proposals similar to those made in 1985 have been made many times since, including calls for dedicated policies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, adequate funding for refuges and more training for police and the judiciary. Some of this would take time to achieve and some is a work in progress: for example, we finally got a national plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in 2024, but we still need more funding for refugees.

Other aspects of domestic violence, such as its prevalence in gay and lesbian relationships, were not yet on the agenda.

‘I had no idea violence against women was so pervasive’

Late in 1987, the federal government established a National Committee on Violence, with gender issues as a key term of reference. Domestic violence became part of a larger conversation about violence. In 1988, the Commonwealth released an action plan, National Agenda for Women, responding to community consultations revealing violence against women and children as a major concern. It was a milestone in the development of national domestic violence policy.

At that point, Australia did not yet have reliable data about rates of domestic violence. In the early 1990s, the national committee gathered and analysed data, which showed the problem was larger than even experienced feminists realised.

When Summers, Australia’s first dedicated professor of family and domestic violence, became head of the Keating government’s Office of the Status of Women in the early 1990s (her second time in the role), she was “staggered” that in focus groups “almost every woman” mentioned violence. “I had no idea violence against women was so pervasive,” she later wrote in her 2018 memoir.

In 1992, the government released the far-reaching and ambitious National Strategy on Violence Against Women, which attributed domestic violence to male attitudes and gendered power.

It produced some action. There were new national guidelines for training people working in the area, which continued to be used for years after. In 1993, there was a Stop Violence Against Women community awareness campaign. In May 1994, the Australian Bureau of Statistics published the first national crime statistics on domestic violence.

In 1996, the ABS conducted the first Women’s Safety Survey, which had a specific focus on physical and sexual violence against women. It found that 5.9% of women had experienced physical violence in the last 12-month period and 1.5% had been sexually assaulted.

1994 was the UN International Year of the Family. An angry, anti-feminist “men’s rights” movement was emerging – explaining men’s violence as a product of their unequal treatment in the family law system. The movement argued women were just as violent as men.

‘De-gendering’ domestic violence in the Howard era

Feminist influence on government policy plummeted when a socially conservative, pro-family Coalition government led by John Howard came to power in March 1996. The government cut many services to women and slashed the funding of the Office for the Status of Women by 40%.

It recognised that domestic violence placed a heavy strain on police, courts and the health system, and reframed it as an issue that undermined family life. Domestic violence was discussed less in the context of addressing violence against women and more as solving problems in the family to avoid family breakdown.

In 1997, Howard convened a National Domestic Violence Summit. He opened it by saying: “We must acknowledge that domestic violence is not a private matter, but a serious issue for our whole society.”

The Howard government overturned the Keating government’s plan and replaced it with an entirely new one. Its new program, Partnerships Against Domestic Violence, left major responsibility to the states. Important initiatives included national annual data on the cost of domestic violence and a focus on Indigenous family violence. The Women’s Safety Agenda, which replaced the program in 2005, continued many of its initiatives.

‘It is Australian men that are responsible’

When Labor won office in November 2007, it reintroduced the language of “violence against women”. In a speech in September 2008, Rudd cited the half million Australian women who experienced violence from their partners. “It is my gender – it is our gender – Australian men – that are responsible,” he said.

In March 2009, the Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children released its national 12-year plan for 2010–22, supported by all state governments. An updated version was released in early 2011, with Julia Gillard as prime minister.

The plan recognised the intersections of domestic and family violence and sexual assault with issues such as homelessness, disability and income support. It sought to stop “violence before it happens in the first place” by changing attitudes to gender, thus returning to a feminist framing.

In the last ten years, domestic violence has gained more public attention than ever before. In 2005, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull described domestic violence as “a national disgrace”. It should be, he said, “UnAustralian” to disrespect women.

His successor, Scott Morrison, commented that a “culture of disrespect towards women is a precursor to violence, and anyone who doesn’t see that is kidding themselves”. Yet during his term in office, the culture of parliament itself was called into question, and there was widespread anger and disappointment about his government’s lack of action on gendered violence.

On March 15, 2021, thousands protested across the country against sexism and gendered violence in #March4Justice rallies, including at Parliament House.

The exclusive, invitation-only nature of the Morrison government’s National Summit on Women’s Safety to discuss the next 12-year national plan was widely criticised, as was its narrow remit. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women called for a separate national plan.

60% of single mothers experienced domestic violence

In July 2022, a few months after Labor won office, Summers released the landmark report The Choice: Violence or Poverty, which found 60% of the 311,000 single mothers living in Australia in 2016 had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a previous partner.

Summers called for the reversal of the “bad policy” introduced by Gillard: the restriction of the parenting support payment to children aged eight and under, rather than 16. In the 2023-24 budget, the government lifted the age for child support from eight to 14. The campaign continues to reinstate the age to 16. Domestic abuse author and campaigner Jess Hill said recently that structural improvements to gender equality, such as the single parenting payment, are key to prevention.

The Albanese government’s iteration of the national plan included the first specific action plan developed in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to focus on their needs, and long-called-for national targets to measure and reduce violence.

In November 2022, Micaela Cronin was appointed as Australia’s inaugural domestic, family and sexual violence commissioner, only the third-such appointment in the world.

We need talk and action

Both sides of parliament now assume – and it is expected of them – that Australia must have a national plan to address problems of domestic and family violence and violence against women. But is there too much talk and not enough action?

It is encouraging that the federal government has heeded the call for a dedicated national plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. But given that First Nations women are 33% more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence than non-Indigenous women, governments must work with affected communities to fund existing programs that work.

It has been almost 40 years of national talk fests, plans and initiatives. The feminist knowledge accrued in a fledgling but impactful women’s refuge movement was core to the 1985 national conference that started the Australian government’s move towards a national domestic violence policy. The expertise of victim-survivors and those who work closely with them – in a sector often stretched to near-breaking – has been central since. It continues to be a crucial resource for decision-makers.

But funding responses have rarely been adequate to the task of translating this generous knowledge-sharing into change.

The current domestic and family violence conversation brings mental health, housing and legal aid funding – among other salient issues – into view. Now, the Australian government response to domestic violence needs to build on the knowledge it has gathered over 40 years – and to meet this expertise with reliable and adequate funding that enables improvements across a range of intersecting services that are built to last.

Note: We discuss some of these issues in more detail in “Too much talk, not enough action? Federal government responses to domestic violence”, in Carolyn Holbrook, Lyndon Megarrity, and David Lowe (eds), Lessons from History: Leading Historians Tackle Australia's Greatest Challenges (NewSouth).![]()

Zora Simic, Associate Professor, School of Humanities and Languages, UNSW Sydney; Ann Curthoys, Honorary Professor in History, University of Sydney, and Catherine Kevin, Associate Professor in Australian History, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.