Australians don’t know and can’t control how data brokers are spreading their personal information. This is the core finding of a newly released report from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

Consumers wanting to rent a property, get an insurance quote or shop online are not given real choices about whether their personal data is shared for other purposes. This exposes Australians to scams, fraud, manipulation and discrimination.

In fact, many don’t even know what kind of data has been collected about them and shared or sold by data firms and other third parties.

Our privacy laws are due for reform. But Australia’s privacy commissioner should also enforce an existing rule: with very limited exceptions, businesses must not collect information about you from third parties.

What are data brokers?

Data brokers generally make their profits by collecting information about individuals from various sources and sharing this personal data with their many business clients. This can include detailed profiles of a person’s family, health, finances and movements.

Data brokers often have no connection with the individual – you may not even recognise the name of a firm that holds vast amounts of information on you. Some of these data brokers are large multinational companies with billions of dollars in revenue.

Consumer and privacy advocates provided the ACCC with evidence of highly concerning data broker practices. One woman tried to find out how data brokers had got hold of her information after receiving targeted medical advertising.

Although she never discovered how they obtained her data, she found out it included her name, date of birth and contact details. It also included inferences about her, such as her retiree status, having no children, not having “high affluence” and being likely to donate to a charity.

ACCC found another data broker was reportedly creating lists of individuals who may be experiencing vulnerability. The categories included:

- children, teenage girls and teenage boys

- “financially unsavvy” people

- elderly people living alone

- new migrants

- religious minorities

- unemployed people

- people in financial distress

- new migrants

- people experiencing pain or who have visited certain medical facilities.

These are all potential vulnerabilities that could be exploited, for example, by scammers or unscrupulous advertisers.

How do they get this information?

The ACCC notes 74% of Australians are uncomfortable with their personal information being shared or sold.

Nonetheless, data brokers sell and share Australian consumers’ personal information every day. Businesses we deal with – for example, when we buy a car or search for natural remedies on an online marketplace – both buy data about us from data brokers and provide them with more.

The ACCC acknowledges consumers haven’t been given a choice about this.

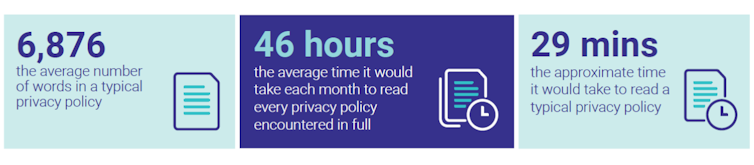

Attempting to read every privacy term is near impossible. The ACCC referred to a recent study which found it would take consumers over 46 hours a month to read every privacy policy they encounter.

Even if you could read every term, you still wouldn’t get a clear picture. Businesses use vague wording and data descriptions which confuse consumers and have no fixed meaning. These include “pseudonymised information”, “hashed email addresses”, “aggregated information” and “advertising ID”.

Privacy terms are also presented on a “take it or leave it” basis, even for transactions like applying for a rental property or buying insurance.

The ACCC pointed out 41% of Australians feel they have been pressured to use “rent tech” platforms. These platforms collect an increasing range of information with questionable connection to renting.

A first for Australian consumers

This is the first time an Australian regulator has made an in-depth report on the consumer data practices of data brokers, which are generally hidden from consumers. It comes ten years after the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) conducted a similar inquiry into data brokers in the US.

The ACCC report examined the data practices of nine data brokers and other “data firms” operating in Australia. (It added the term “data firms” because some companies sharing data about people argue that they are not data brokers.)

A big difference between the Australian and the US reports is that the FTC is both the consumer watchdog and the privacy regulator. As our competition and consumer watchdog, the ACCC is meant to focus on competition and consumer issues.

We also need our privacy regulator, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), to pay attention to these findings.

There’s a law against that

The ACCC report shows many examples of businesses collecting personal information about us from third parties. For example, you may be a customer of a business that only has your name and email address. But that business can purchase “data enrichment” services from a data broker to find out your age range, income range and family situation.

The current Privacy Act includes a principle that organisations must collect personal information only from the individual (you) unless it is unreasonable or impracticable to do so. “Impracticable” means practically impossible. This is the direct collection rule.

Yet there is no reported case of the privacy commissioner enforcing the direct collection rule against a data broker or its business customers. Nor has the OAIC issued any specific guidance in this respect. It should do both.

Time to update our privacy laws

Our privacy law was drafted in 1988, long before this complex web of digital data practices emerged. Privacy laws in places such as California and the European Union provide much stronger protections.

The government has announced it plans to introduce a privacy law reform bill this August.

The ACCC report reinforces the need for vital amendments, including a direct right of action for individuals and a rule requiring dealings in personal information to be “fair and reasonable”.![]()

Katharine Kemp, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law & Justice, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.