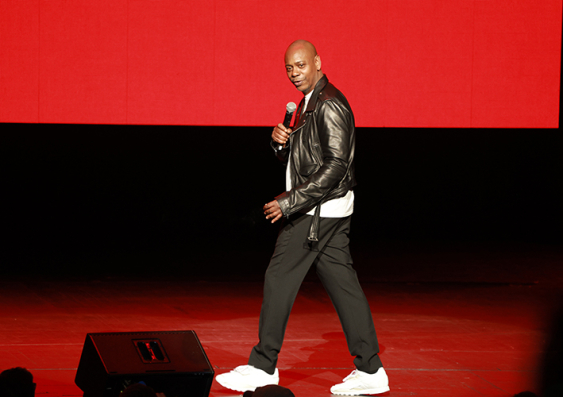

Dave Chappelle is known for ‘punching down’ on trans people – now he’s targeting disabled people

In The Dreamer, Chapelle laughs at disability, bisexuality and gay men. But his jokes continue to come back to one target: the transgender community.

In The Dreamer, Chapelle laughs at disability, bisexuality and gay men. But his jokes continue to come back to one target: the transgender community.

Dave Chappelle’s latest Netflix special, The Dreamer, opens with a story about meeting Jim Carrey, who, at the time, was method acting and portraying comedian Andy Kaufman.

Chappelle recalls being “very disappointed” at having to pretend to be speaking to Kaufman, when he could clearly see it was Carrey. The punchline? “That’s how trans people make me feel.”

Whether or not non-transgender people find it funny, it is a joke that stabs at the fundamental insecurity of being trans. It takes the stance of biological essentialism, opens in a new window: that people have innate and intractable traits by virtue of their biology.

Biological essentialism has been used, opens in a new window by the anti-trans, opens in a new window lobby to deny that trans women are women and trans men are men, and to justify sexism and racism before that, opens in a new window.

Chappelle’s Netflix specials have become notorious for his jokes targeting the transgender community, but Chappelle has claimed his comedy is more nuanced, opens in a new window and artistic than his critics allow.

He claims to be an equal opportunity offender, “punching down” (his words) to all minorities equally. To prove this point, in The Dreamer he takes on what he calls “handicapped jokes”.

While the word “handicapped” was once used to describe people with disability, it is now considered offensive, opens in a new window. Chappelle is either unaware or just doesn’t care that the term is decades out of date.

Comedy, at its best, draws from and reveals insight into the human condition. It slips into mockery when, bereft of understanding, it does nothing more than mirror prejudice.

Chappelle’s first disability joke has the potential to be clever and insightful. He says:

there’s probably a handicap in the back right now ’cause that’s where they make them sit.

A joke about the placement of people with disability at the back of the theatre is clever as it unmasks social disadvantage. In different hands, it could be a reflection on the social model of disability, opens in a new window.

The social model of disability says the problem of disability is not “handicapped” bodies but the social environment designed to exclude and marginalise them. For example, a wheelchair user is not disabled because they cannot walk (they have wheels for mobility), but because of a lack of access to ramps – or a theatre which insists they sit at the back of the room.

But clever turns to mockery with a visual punchline, as Chappelle twists his hand and walks like a “cripple”. It is mockery bereft of understanding.

A crass attack on paraplegic sexual function follows: “Who the fuck invites a paraplegic to an orgy?”. It’s ableism masquerading as comedy.

Ableism, opens in a new window refers to stereotypical attitudes and behaviours that dehumanise people with disability, treating them as different, less than, incapable, foolish, laughable, excludable. In this case, Chappelle repeats the damaging and false stereotype, opens in a new window that people with disability are asexual and unsexy.

Australia’s Disability Royal Commission heard, opens in a new window how ableism, especially as propagated in the media, drives violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability. It noted we learn our language and attitudes from the media and popular culture, which often leads to abusive behaviour in public and online.

When comedy relies on humiliation and cruelty to earn its laughter it can have serious consequences. Rather than propagate ableism, comedy can deconstruct it, opens in a new window, revealing the absurdity of discrimination, and questioning notions of normality, abnormality and ideas of difference.

But watching the special, it feels like disability is not Chappelle’s real target. Instead, it seems he embraces being an “equal opportunity” offender who mocks disability as a defence for his long-running transgender jokes.

Witty transgender comedy might highlight the social issues trans people face, but Chapelle exemplifies those issues. In The Dreamer, he makes the tired joke that if he was arrested in California he’d claim in court that he identified as a woman to be sent to women’s jail so he could have sex with women.

His jokes rely on prevailing disgust about transgender bodies and increasingly politicised insistence that transgender people are not real women or men. These views shared in popular culture are coming to inform, opens in a new window anti-trans policy in healthcare, education and the justice system.

As the majority of the general population do not know a trans person, opens in a new window, the media has significant influence over perceptions of trans people.

Throughout four Netflix specials, Chapelle has made no effort to understand the object of his jokes or the impact of his mockery on their daily lives. While trans representation in the media is improving, trans people are still exposed to a plethora of negative depictions, opens in a new window of their identities in the media across a range of mediums. Research, opens in a new window shows this is significantly associated with clinical levels of depression, anxiety and psychological distress.

Near the end of The Dreamer, Chappelle paints himself as the victim of the “unjust” LGBTQI+ campaign against his comedy, which included Chappelle being physically attacked, opens in a new window on stage at a 2022 show.

Physical violence is never justified. However it should be noted comedy which “punches down” on trans people helps to drive, opens in a new window the negative perceptions that lead to violence, opens in a new window against queer people that we see on social media feeds and in the daily experience of transgender people globally.

Chappelle is an influential comedian who proudly punches down. It is true he is an egalitarian bully. In The Dreamer, he laughs at disability, bisexuality and gay men. But his jokes continue to come back to one target: the transgender community. When will we say enough is enough? When will we stop laughing?

Shane Clifton, opens in a new window, Associate Professor of Practice, School of Health Sciences and the Centre for Disability Research and Policy, University of Sydney, opens in a new window and Jemma Clifton, opens in a new window, Research officer, UNSW Sydney, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.