Extreme weather is landing more Australians in hospital – and heat is the biggest culprit

As Australia heads into summer with an El Niño, it’s important to understand and prepare for the health risks associated with extreme weather.

As Australia heads into summer with an El Niño, it’s important to understand and prepare for the health risks associated with extreme weather.

Hospital admissions for injuries directly attributable to extreme weather events – such as heatwaves, bushfires and storms – have increased in Australia over the past decade.

A new report, opens in a new window from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) shows 9,119 Australians were hospitalised for injuries from extreme weather from 2012-22 and 677 people died from these injuries in the decade up to 2021.

In 2021-22, there were 754 injury hospitalisations directly related to extreme weather, compared to 576 in 2011-12.

Extreme heat is responsible for most weather-related injuries. Exposure to prolonged natural heat can result in physical conditions ranging from mild heat stroke, to organ damage and death.

As Australia heads into summer with an El Niño, it’s important to understand and prepare for the health risks associated with extreme weather.

Extreme weather-related hospitalisations have spiked at more than 1,000 cases every three years, with the spikes becoming progressively higher. There were:

In each of these three years, extreme heat had the biggest impact on hospital admissions and deaths.

Extreme heat accounted for 7,104 injury hospitalisations (78% of all injury hospitalisations) and 293 deaths (43% of all injury deaths) in the ten year period analysed.

In 2011-12, there were 354 injury hospitalisations directly related to extreme heat. This rose to 579 by 2021-22.

Over the past three decades, extreme weather events have increased in frequency, opens in a new window and severity, opens in a new window.

In Australia, El Niño drives a period of reduced rainfall, warmer temperatures and increased bushfire danger.

La Niña, on the other hand, is associated with above average rainfall, cooler daytime temperatures and increased chance of tropical cyclones and flood events.

Although similar numbers of heatwave-related hospitalisations occurred in El Niño and La Niña years studied, the number of injuries related to bushfires was higher in El Niño years.

During the 2019–20 bushfires, in the week beginning January 5 2020, there were 1,100 more hospitalisations than the previous five-year average, an 11% increase.

Although El Niño hasn’t directly been proved as the cause for these three spikes, according to the Bureau of Meteorology, two of the three years (2016-17 and 2019-20) were El Niño summers. And the other year (2013-14) was the warmest neutral year on record at that time.

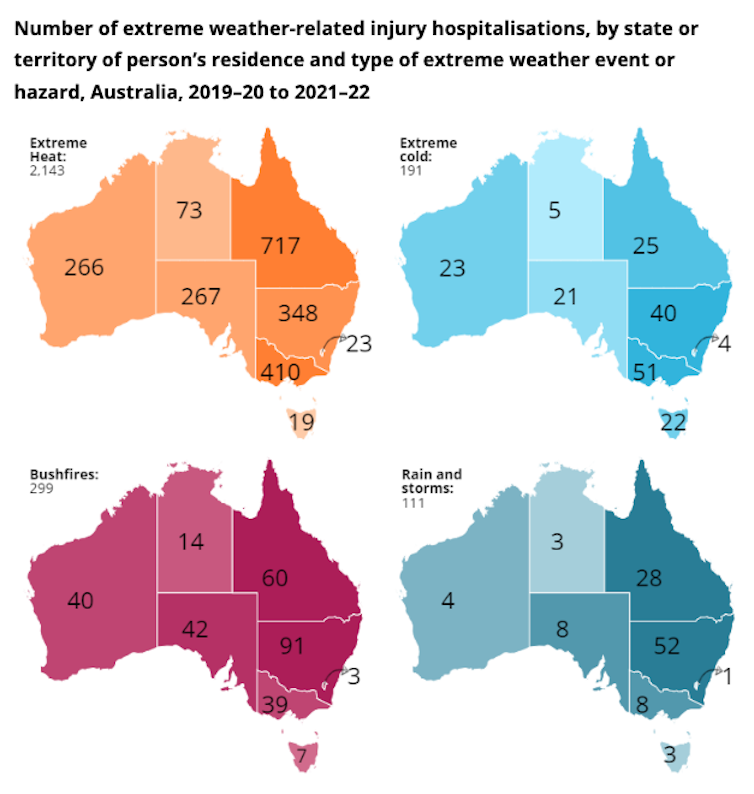

Exposure to excessive natural heat was the most common cause leading to injury hospitalisation for all the mainland states and territories. From 2019 to 2022, there were 2,143 hospital admissions related to extreme heat, including:

AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database, opens in a new window, CC BY, opens in a new window

The report also includes state and territory data on hospitalisations related to extreme cold and storms.

During the ten-year period analysed, there were 773 injury hospitalisations and 242 deaths related to extreme cold. Extreme rain or storms accounted for 348 injury hospitalisations and 77 deaths.

From 2019 to 2022, there were 191 hospitalisations related to extreme cold, with Victoria recording the highest number (51, compared to 40 in next-placed NSW). During the same period there were 111 hospitalisations related to rain and storms, with 52 occurring in NSW and 28 in Queensland.

Over the ten-year period studied, there were 894 hospitalisations and 65 deaths related to bushfires.

Bushfire-related injury hospitalisations and deaths peaked in 2019–20, an El Niño year with 174 hospitalisations and 35 deaths. The two most common injuries that result from bushfires are smoke inhalation and burns.

During the 2019–20 bushfires, in the week beginning 5 January 2020 there were 1,100 more respiratory hospitalisations than the previous five-year average, an 11% increase.

The greatest increase in the hospitalisation rate for burns was 30% in the week beginning December 15 2019 — 0.8 per 100,000 persons (about 210 hospitalisations), compared with the previous 5-year average of 0.6 per 100,000 (an average of 155 hospitalisations).

Anyone can be affected by extreme weather-related injuries but some population groups are more at risk than others. This includes older people, children, people with disabilities, those with pre-existing or chronic health conditions, outdoor workers, and those with greater socioeconomic disadvantage, opens in a new window.

People in these groups may have reduced capacity to avoid or reduce the health impacts of extreme weather conditions, for example older people taking medication may be less able to regulate their body temperature. “Thermal inequity” includes people living in poor quality housing who have difficulty accessing adequate heating and cooling.

For heat-related injuries between 2019–20 and 2021–22, people aged 65 and over were the most commonly admitted to hospital, followed by people aged 25–44.

Across age groups, men had higher numbers of heat related injury hospitalisations than women. This difference was most notable among those aged 25-44 and 45-64 years, where over twice as many men were hospitalised due to extreme heat as women.

The AIHW data only includes injuries which were serious enough for patients to be admitted to hospital; it doesn’t include cases where patients treated in an emergency department and sent home without being admitted.

It includes injuries that were directly attributable to weather-related events but does not include injuries that were indirectly related. For example, it doesn’t include injuries from road traffic accidents that occur due to wet weather, since the primary cause of injury would be recorded as “transport”.

Improved surveillance of weather-related injuries could help the health system and the community better prepare for responding to extreme weather conditions. For example, better data aids communities in predicting what resources will be needed during periods of extreme weather.

A more complete picture of injuries during weather events could also be used to inform people of actions they can take to protect their own health. Given a predicted hot summer, this could be a matter of life or death.

This article was co-authored by Sarah Ahmed and Heather Swanston from the Injuries and System Surveillance Unit at the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

![]()

Amy Peden, opens in a new window, NHMRC Research Fellow, School of Population Health & co-founder UNSW Beach Safety Research Group, UNSW Sydney, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.