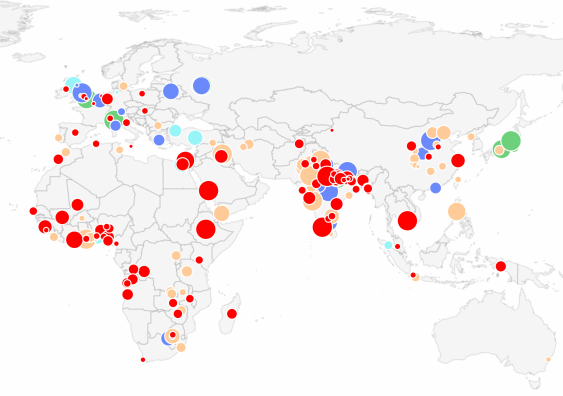

Researchers have created the most comprehensive database of deaths and injuries caused by crowd accidents ever compiled, which they hope will improve safety at mass gatherings across the world.

The directory features details of 281 major global incidents occurring between 1900 and 2019 that resulted in at least one death, or 10 people being injured.

And the data shows, opens in a new window that India and West Africa are increasingly becoming hot spots for crowd accidents, with religious festivals overtaking sporting events in the past 30 years as the most likely situation to result in a dangerous crush.

Other areas where numerous deadly incidents have occurred in the past few years include South-East Asia and the Middle East.

Overall, serious crowd accidents across the globe have risen dramatically over the past 20 years – from an average of around three per year between 1990 and 1999, to nearly 12 per year between 2010 and 2019 – although it is acknowledged some of that may be due to the growth of the internet and social media which ensures incidents are more widely reported.

Regulations add protection

The researchers, including lead author Project Associate Professor Claudio Feliciani from the University of Tokyo and Dr Milad Haghani from UNSW Sydney, presented their findings in the Safety Science, opens in a new window journal.

And they say it is imperative that safety experts have such a complete database and detailed analysis of crowd accidents to help implement new safeguards to reduce the dangers in future.

“Just in the past 20 years alone around 8000 people have been killed in crowd accidents and more than 15,000 have been injured,” said Dr Milad Haghani from UNSW’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, opens in a new window.

“Over time, the share of sport events in crowd accidents has declined, and instead, religious gatherings have become more notably present in the statistics.

“We have strong indications that the introduction of more regulations regarding crowd safety at sporting events in the past 30 years has added an extra layer of protection.

“Another interesting observation is the association of accident rates to the income level of the countries where they happen, with low-and-middle-income countries being more represented in the records.

“India and, to a somewhat lesser extent West Africa, appear to be hot spots for crowd accidents. These are rapidly developing regions, with a quick increase in population and where infrastructure is struggling to keep pace with the inflow of people from rural to urban areas.

“Northern India, in particular, is a densely populated area with solid religious traditions leading people to gather in millions over short period of times.”

Thousands of people gather to celebrate the Holi festival in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan in 2019. Photo from Shutterstock

Almost all crowd accidents recorded in the 1970s occurred at sporting events, but improved safety appears to be linked to the publication of the first edition of the so-called ‘Green Guide’ in 1973 which has now become recognised around the world as best practice for the design and planning, and the safety management and operation of sport grounds.

In their paper, the researchers note: “We hope that the lessons learned in the UK, where crowd accidents used to be common in the past and led to better practices, could be applied on a global basis, although we are perfectly aware that many countries lack the financial needs for such improvements.”

Dangers of religious events

While accidents at sporting events are proportionately falling, the ratio of dangerous incidents at religious gatherings has been steadily on the rise.

A/Prof Feliciani says implementing the same improved safety protocols at religious events is much harder since they are often non-ticketed with no limits on the numbers of people who can attend. In addition, they most often are held over much larger areas which makes management of the crowd especially difficult.

Almost 70 per cent of the accidents which occurred in India between 2000 and 2019 were related to religious events. Many of those accidents occurred close to rivers or in areas close to water because bathing takes an important role in Hindu rituals.

Accidents have frequently occurred on bridges (which act as a bottleneck), at ferry terminals (basically a dead end) or on riverbanks (where people enter the water to later reverse their direction, thus creating a complex and conflicting motion pattern).

But train stations or transportation terminals have also often been the theatre for disasters in the region.

The Har Ki Pauri ghat, or steps, in the holy city of Haridwar are the location for religious festivals such as the Kumbha Mela and the Ardh Kumbh Mela where thousands of pilgrims come to bathe in the River Ganges. Photo from Shutterstock

“I think the problems we see from the data in India, where there are a large number of accidents linked to religious festivals, is mostly about financial constraints,” he says.

“They know these deadly crowd events are happening and they know they should be doing something more, but probably they do not have access to the same money and the same technology that is available in wealthier countries.

“There is also a difference in the level of knowledge in terms of crowd safety at religious festivals compared to sports events.

“At a sports stadium there are often lots of people attending on a regular basis. The people in charge of safety are doing that job regularly and they know what to do.

“For a religious festival, it might only happen once every 50 years in a certain place. Those responsible for crowd safety might not have ever dealt with a mass gathering in that location before or been in control of such a big event and therefore don’t know the protocols in as much detail.”

Australia: don’t get complacent

Despite the relative lack of crowd accidents in Australia, the researchers have warned event organisers and attendees not to be complacent about the potential level of danger.

The only Australian incident in the database is the crush during a performance by Limp Bizkit, opens in a new window at the 2001 Big Day Out event in Sydney which resulted in the death of a young woman.

“I speak with a lot of professionals on a daily basis and they regularly see near-misses at events that thankfully do not result in deaths or serious injuries,” Dr Haghani says.

“Those incidents might not get any publicity, and information about what actually happened might not subsequently be shared so the danger is that it could be just a matter of time before something bad happens in Australia.”

A/Prof Feliciani says: “There were very few incidents in South Korea for many decades and then unfortunately the very serious crush at the Halloween festival in 2022 in Seoul, opens in a new window where nearly 160 people died.

“So I think it is always important to be careful and mindful of crowd safety wherever you are and not to become complacent.”

Dr Haghani and A/Prof Feliciani will both be presenting at the Crowd Safety Summit Australia, opens in a new window which is being held at UNSW next week.

The event has attracted international crowd safety practitioners, academics and stakeholders who will exchange ideas and experiences and develop a roadmap for better public safety worldwide in the decades ahead.

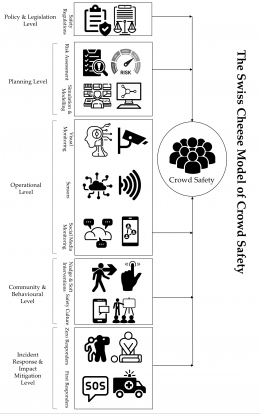

Swiss Cheese and Vision Zero

Dr Haghani, who is the Chair and chief organiser of the Summit, says the expert community must take inspiration from the Vision Zero traffic safety initiative which works on the principle that no-one should be killed or seriously injured using road networks.

The Swiss Cheese model of crowd safety introduces numerous layers of protections to prevent accidents at mass gatherings. Image supplied by Dr Milad Haghani

“At the Crowd Safety Summit I will be proposing that a similar target needs to be adopted for crowd safety,” Dr Haghani says.

“To achieve that, I believe what I call the ‘Swiss Cheese’ model of crowd safety should become the norm. This system incorporates a multitude of safety protection layers, including regulations and policymaking, planning and risk assessment, operational control, community preparedness, and incident response.

“The underlying premise is that if one, or more, of the layers do not work then the other layers can still prevent an accident.

“In practice, such a model requires a more effective implementation of technology to enable the provision of real-time data, improved communication and coordination of efficient incident responses.

“But we also need to pay more attention to the role of public education, and raise awareness, as well as promoting crowd safety culture at broad community levels.

“In that way, we have the potential to empower individuals with the knowledge and skills that can prevent life-threatening outcomes even when all other layers, such as planning and operational control, may have failed.”