The Albanese government’s housing package moved a step closer to delivery with the recent release of draft legislation. The bills are expected to be tabled in parliament soon. After a decade of general federal disengagement from housing policy (first home ownership being the main exception), this is more than welcome.

At the same time, the proposed laws don’t give enough priority to the need for a coherent approach to a complex housing system. Multi-faceted problems such as homelessness, unaffordable rents, mortgage stress and a lack of social housing demand joined-up solutions. Housing knowledge and policy-making capacity within government have been badly eroded and must be restored.

The draft legislative package comprised three bills (and a helpful explanatory memorandum):

National Housing Supply and Affordability Council Bill

Housing Australia Future Fund Bill

Treasury Laws Amendment (Housing Measures) Bill.

Beyond this, the National Housing and Homelessness Plan now being developed by the government should provide the vital strategic framework that has been so glaringly absent. This means it could be even more important than the measures in the draft bills. Arguably, the plan should also be enshrined in law.

What’s good about the package?

In our submission on the draft package, we commend the progress towards reasserting Commonwealth leadership on housing. State and territory commitments and actions are vital, too, in confronting Australia’s mounting and complex housing challenges. But federal engagement and ambition are essential to make any significant and lasting progress.

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council promises to restore the foundation for evidence-based policy once provided by the former National Housing Supply Council.

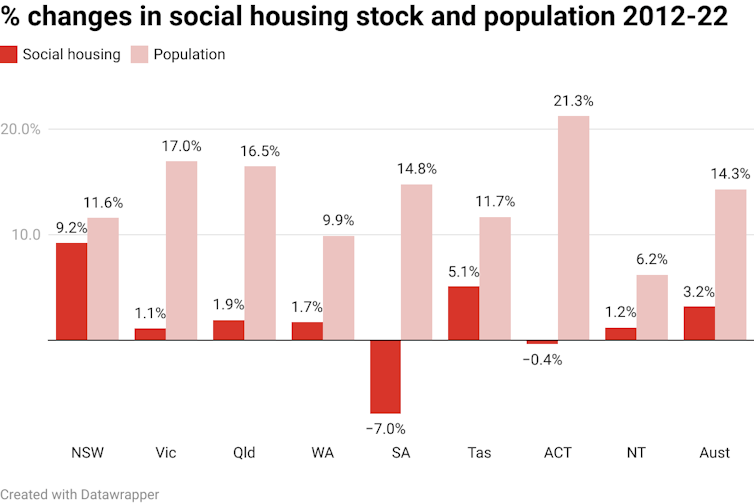

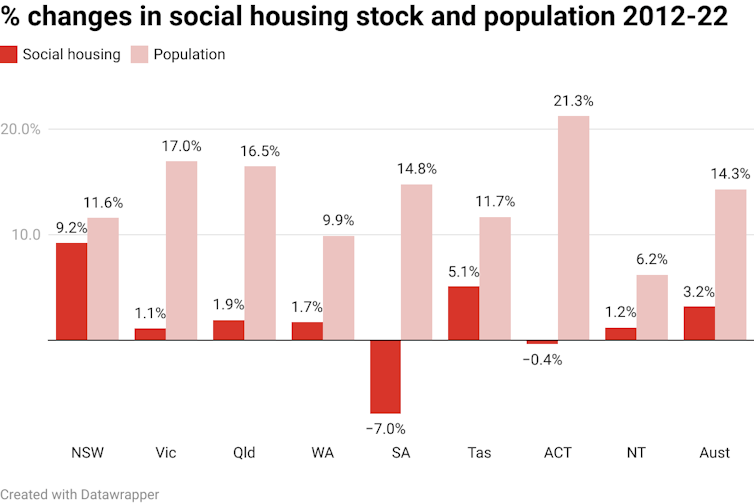

Similarly, after more than ten years of negligible investment in new social and affordable housing, the $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund is certainly a laudable commitment. However, the aim of building 30,000 new social and affordable housing units over five years is relatively modest. We estimate current unmet need for social housing equates to 437,000 households.

The recent National Housing Accord on expanded construction output could also play a meaningful role. Full details are yet to be released.

Image: The Conversation. Data: Author provided from Productivity Commission Reports on Government Services, Australian Bureau of Statistics, CC BY.

And what will it take to fix the housing system?

As argued in our book, the declining performance of Australia’s housing system is not just a matter of historically miserly government funding. It’s also a result of policymaking failure.

That failure reflects the long-term deterioration and fragmentation of governmental capacity in this realm. At both federal and state levels, the past 25 years have seen the progressive disappearance or downgrading of ministerial housing portfolios and associated departments. At the same time, housing policy has been increasingly viewed as a narrowly defined subset of welfare policy.

These changes have eroded housing policy knowledge and policymaking capacity within government. They’re an aspect of the hollowing out of government across many policy fields in Australia and overseas. Arguably, it has had particularly far-reaching impacts on housing in Australia.

Partly for these reasons, the proposed upgrading of the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation to a national housing agency, Housing Australia, is another commendable aspect of the legislation.

What more should the government do?

Potentially more of a game-changer than the measures in the draft bills is the promised National Housing and Homelessness Plan. Since housing is a complex and interactive system, micro-measures targeting selected aspects of that system are liable to have minimal or even counter-productive impacts. Housing therefore demands strategic policymaking (rather than an incremental or reactive approach).

This is why Australia should emulate the Canadian government by enshrining the National Housing and Homelessness Plan in law. Doing so would reduce the risk of a future administration emasculating or abandoning the structure.

As for the three draft bills, a crucial enhancement would be to strengthen the status, capacity and responsibilities of Housing Australia.

Here we again take inspiration from across the north Pacific. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) has played a crucial strategic role as a national housing agency over decades. The UK’s Scottish Homes (1989-2001) and Housing Corporation (1964-2008) were similarly influential in informing, co-ordinating and delivering housing policy. Importantly, they also championed housing within government.

With these examples in mind, there is a strong case for Housing Australia to be:

given a wider analytical and research role to inform policymaking and support the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council

tasked with formulating the National Housing and Homelessness Plan and co-ordinating its implementation and review

made responsible for the progress and oversight of the National Housing Accord

charged with informing the re-negotiation of the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement between the Commonwealth, states and territories.

In short, to boost the chances that the current housing policy impetus can be sustained, the proposed institutional reforms must be both strengthened and embedded.

Hal Pawson, Professor of Housing Research and Policy, and Associate Director, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.