How learning to be a 'zero responder' can help save lives in an emergency

A UNSW Sydney academic says staying calm is NOT the right thing to do if you need to evacuate from an emergency or escape a mass shooting event.

A UNSW Sydney academic says staying calm is NOT the right thing to do if you need to evacuate from an emergency or escape a mass shooting event.

Neil Martin

n.martin@unsw.edu.au

Everyone has heard of ‘first responders’ – members of the emergency services who are first on the scene to provide aid and assistance during an emergency.

But do you know what a ‘zero responder’ is? Or that a leading crowd safety expert believes they can be equally crucial in saving lives when disasters strike.

Dr Milad Haghani, a senior lecturer in UNSW Sydney’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, has extensively researched the way crowds react in emergency situations such as a plane crash, or a fire in a building, or during a mass shooting event.

Read more: 'Be alert, avoid complacency,' crowd safety expert says ahead of busy festive period

And he is passionate about spreading the message regarding zero responders – that is, members of the public unfortunately caught up in such incidents. His detailed studies show that the way they react individually, and as a group as a whole, can dramatically affect the outcome in terms of casualties.

Unfortunately, people unexpectedly thrust into a disaster are largely untrained to deal with such an experience, which is why Dr Haghani is keen to educate people on the best ways they can act to improve not only their own chance of survival, but also that of others at the scene.

And his advice is to NOT to stay calm and escape in a slow and measured way, but instead to rush to safety as quickly as humanly possible, because this behaviour actually helps everyone.

“In a situation where there is an external threat, like a fire or someone with a gun, in a relatively enclosed space then there isn’t going to be any professional management of the situation from police, or the fire brigade, for maybe a couple of minutes at absolute best,” Dr Haghani says.

“That’s why I call the people unfortunately caught up in those scenarios ‘zero responders’ because they are there even before the first responders arrive.

“They are the ones in charge of saving their own lives and those of others based on the decisions they take – and there are definitely things people can do that will help.

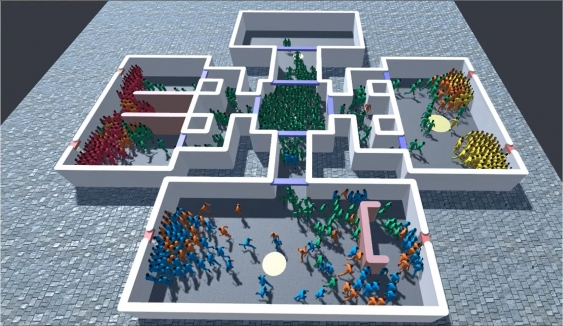

Dr Milad Haghani has created his own computer simulation model to help create best-practice guidelines for people to escape as quickly as possible from an emergency situation in an enclosed area. Photo from Dr Milad Haghani

“Unfortunately, I think there has been a lot of misinformation put out previously. There is language about staying calm and not panicking. I say, ‘No! Do not stay calm’. That is absolutely not good for you.

“You should try to evacuate as quickly as possible, even if you get to an exit where there is a bottleneck and a larger group of people. It’s not about everyone being comfortable and polite, it is about getting as many of those people out as soon as they can all go.”

Dr Haghani conducts tests at UNSW with volunteers that re-create emergency situations, allowing him to track the individual movements of people and the behaviour of a crowd as a whole to calculate the fastest and most efficient evacuation procedures.

He also runs computer models to help assess the way certain decisions can impact on the time to taken to clear a particular area.

And the research shows that if only 50 per cent of people that are deemed to be zero responders in an emergency situation react in the way Dr Haghani says they should, then the outcomes improve for every single individual in the group.

Which is why he hopes his message can be taken on board by as many as possible.

“I have tested these things with real people in experiments and also developed computer simulations to analyse them as well,” he explains.

“For example, there is a notion that when you get to a bottleneck, say a narrow doorway, then if you try to go too fast it will actually be slower. And that means people think you should be more deliberate.

“That is absolutely not the case and my experiments and simulations have shown it again and again. If everyone were to follow my advice, and go as fast as is possible, then the whole crowd escape could be 50 per cent faster and more efficient.

Dr Milad Haghani has conducted experiments using real people to analyse what behaviours result in the most efficient evacuations for both individuals and large groups. Video from Dr Milad Haghani

“At a bottleneck, have the mindset of rushing through. I don’t mean be aggressive and push and shove, but just make sure there are no gaps between you and the person in front. It might feel slightly uncomfortable for a short period, but this is about keeping the flow of the evacuation and escaping that incident that might be endangering your life.”

Dr Haghani has the data to back up his advice.

“In one experiment I asked 120 people to go through a narrow exit, a bottleneck, in a very respectful and calm way where they were not making contact with anyone,” he adds.

“Then I repeated the evacuation, but this time I had told 20 per cent of the group to not be calm and to get through as quickly as they could – even if that meant having some body contact with others. And I noted the difference in the time taken to clear the whole crowd.

“The experiment was repeated with different numbers of people in that crowd being told to rush and ultimately what I found was that even when only half the group was acting in that way, rather than staying calm, the evacuation was close to peak efficiency.

“That means, even if a significant number of people in that situation are actually employing a bad strategy of being calm and going slowly, you and others can give everyone the benefits by acting in the most favourable way.

“Ultimately, I think this needs to be translated into a comprehensive training tool which is currently missing from every guideline in terms of preparing individual people how to react.”

Not surprisingly, in the modern age of social media, Dr Haghani has strongly warned against anyone – in any situation that might potentially endanger their life – from wasting precious moments filming the incident on their mobile for likes and shares.

“If there is a credible threat, let’s say you hear a gunshot, the key factor may be your reaction time. And the best reaction time is zero seconds,” he says.

“Do not hesitate to get away. Do not pull out your phone and try to get a good video for later, because that could be terrible.

“Try to react instantly and make your choice quickly about which direction you should escape, that being the one that seems to you to be the quickest and least congested. If everyone does the same thing, and there are multiple exit points, then the crowd will be distributed evenly which also helps the whole group.

“But I would also advise not to be scared of changing your mind. If you go to one exit and you think it’s too crowded and you believe there is another exit that will be quicker then go for it.

“Go at your maximum speed. Do not stay calm, do not walk and take your time. Everything you do should be done as quickly as you can possibly do it.”

Dr Haghani’s research and models are largely based on the assumption that people are physically capable of moving to safety unassisted.

However, he is next planning to simulate a scenario in an aged-care facility where the majority of people may require assistance to evacuate, as well as analysing the evacuation of a mixed crowd (able-bodied and mobility restricted) where only a small portion of people are in need of assistance to test the effect of assistance and different strategies of assistance on the overall system performance.