Last week, the Albanese government took another important step towards the referendum on a Voice to Parliament. It introduced a bill, opens in a new window to make changes to our referendum process, including new arrangements for public education and campaign finance.

Getting the referendum process right is essential if the Voice vote is to be fair and informed. So, what changes has the government proposed, and will they help to achieve that?

Modernising our outdated referendum rules

It is more than 20 years since Australia held its last referendum in 1999. That is the longest period in our history without a vote on constitutional change. So much time has passed that only Australians over 40 have any experience voting in a referendum.

One of the effects of this long gap is that the laws governing the referendum process have become stale. Unlike election laws, they have not always been updated to reflect changes in voting and campaigning. And some aspects – like the design of the referendum pamphlet – have barely changed in over a century.

With a Voice referendum on the horizon, it was clear a big update was needed. A major parliamentary inquiry, opens in a new window said as much in December 2021 when it called Australia’s Referendum Act, opens in a new window “outdated and not suitable for a referendum in contemporary Australia”.

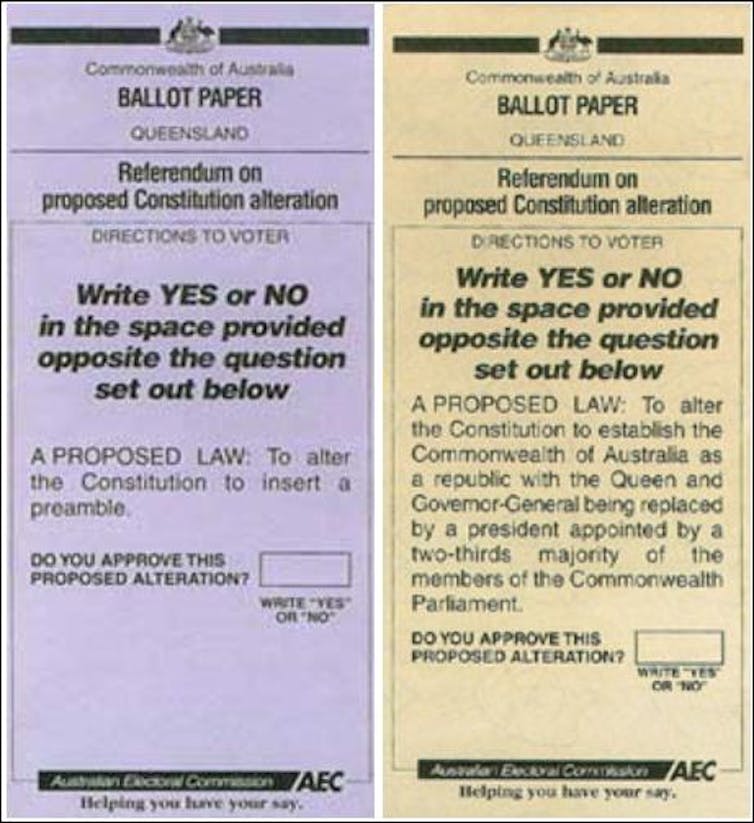

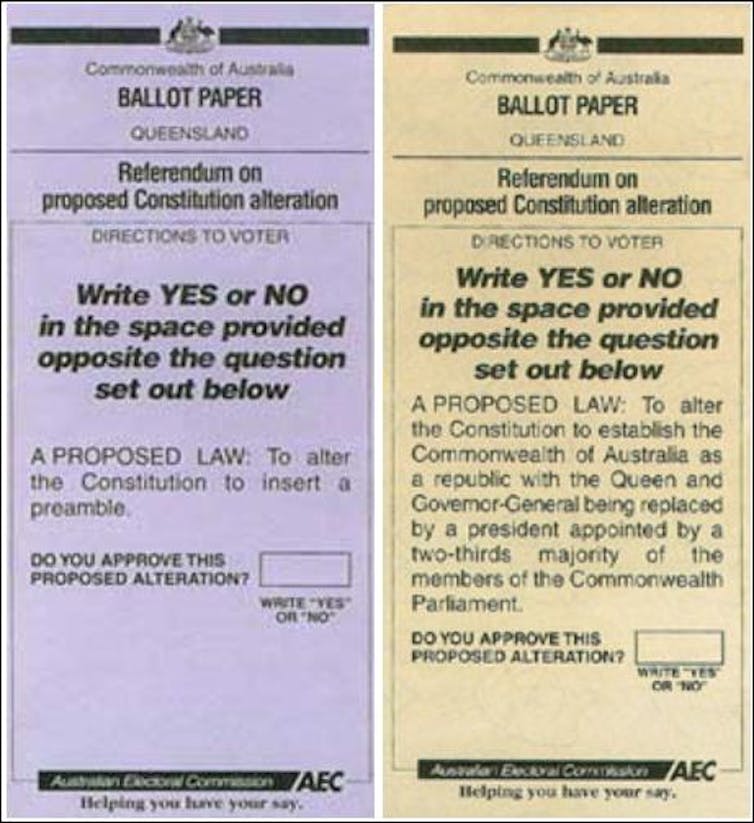

The last time Australians were asked to consider a constitutional change was in 1999, when the republic referendum was held and failed. Parliament of Australia

The federal government proposes to modernise the law in several areas. The arrangements for postal voting, authorisation of advertisements and ballot scrutiny would all be brought into line with election laws.

But the more noteworthy changes concern public education and campaign finance. These are the most sensitive areas covered by the bill and will attract the most debate in the months ahead.

Scrapping the pamphlet

In a surprise move, the government wants to drop the official Yes/No pamphlet for the Voice referendum.

For over a century, the usual practice has been for governments to mail voters a pamphlet that contains official Yes and No arguments authorised by members of parliament.

The Bill suspends this practice for any referendum held during this parliamentary term. The government says the circulation of a hard-copy pamphlet is outdated in the digital age and that MPs can make their case in other ways, including via television and social media.

The pamphlet has never lived up to its promise as an educative tool. It is designed to persuade, not inform. Past pamphlets have often contained exaggerated or misleading claims that seem designed to confuse or frighten voters. In 1974, for example, the No campaign said “democracy could not survive” a change to how electorates were drawn. At its worst, the pamphlet can serve to spread misinformation rather than counter it.

Read more: What do we know about the Voice to Parliament design, and what do we still need to know?

All the same, many voters will want an accessible source of official information, both on the proposal and the arguments for and against change, to help them make up their own mind. A hard-copy pamphlet can serve that purpose, even in a digital age.

Rather than ditching the pamphlet, the parliament should reform it. It should be revised to include a clear, factual explanation of the proposal, just like similar pamphlets in Ireland, California and New South Wales. The arguments for and against should be shorter, calmer and more considered. And if we can’t trust politicians to formulate quality Yes and No cases, we should give that task to public servants or an independent body.

Civics education

The government says it wants to focus its public education efforts on a civics campaign that will provide voters with information about “Australia’s constitution, the referendum process, and factual information about the referendum proposal”. The bill temporarily lifts a block on government spending to allow that to happen.

This move is promising, and there is a precedent for it – the Howard government funded a neutral education program for the republic referendum.

But the government has not provided any detail on how the campaign would run. Careful design is crucial if it is to be trusted and effective.

Here the government should heed the recommendation of the 2021 parliamentary inquiry and establish an independent referendum panel to advise on, or even run, the civics campaign. A 2009 inquiry, opens in a new window suggested the same.

To ensure public confidence in the body, its membership could be appointed by the prime minister in consultation with other parliamentary leaders. Ideally, the members would come from diverse backgrounds. The inquiry recommended a panel comprising “constitutional law and public communication experts, representatives from the AEC and/or other government agencies, and community representatives”.

It was disappointing that last week’s announcement made no mention of this idea. The creation of a well-designed, independent body to oversee public education could make a huge difference to voters looking for accessible, balanced and reliable information on the Voice.

No public funding for the Yes and No campaigns

The government has said it won’t provide public funding to the Yes and No campaigns. Both sides will instead have to rely on private fundraising to pay for advertising and other campaign activities.

This approach has been the norm over Australia’s referendum history. Howard allocated public money to the Yes and No sides in 1999, but that remains a one-off.

Transparency and accountability in campaign finance

The bill makes long-overdue changes to the rules on referendum campaign finance.

Labor wants campaigners to publicly report donations and expenditure that exceed the disclosure threshold (which is currently set at $15,200). It would also restrict foreign influence by banning foreign donations over $100.

These changes bring referendum laws into line with ordinary election laws – for better and worse.

They will help to improve accountability and transparency. But they replicate the failings of election laws and fall well short of best practice.

The disclosure threshold is too high, ensuring some large donations will remain anonymous. And Australians will have to wait until after the referendum to find out who gave money to the Yes and No campaigns.

A better approach would be to set a lower threshold and require real-time disclosure, as occurs in some states.

The dangers of last-minute rule changes

Australia’s referendum laws need an overhaul. The government’s bill is a step in the right direction, although it falls short in important areas. It has been referred to the electoral matters committee and will be debated in the new year.

It is unclear if the major parties will reach consensus on all aspects of the bill. The decision to axe the pamphlet has already proved contentious. The Liberal opposition has said that suspending the pamphlet is “worrying” and “puts a successful referendum at risk”.

Unfortunately, conversations about the referendum process are much harder on the eve of a vote. Rule changes, even when well-intentioned, are more likely to be viewed as strategic or self-interested.

Given our long referendum hiatus, it is a shame parliament has waited until now to seriously consider these process reforms.

However, there is now a short window for parliamentarians to work seriously and cooperatively towards a framework that will ensure a fair and informed vote on the Voice to Parliament.

Paul Kildea, opens in a new window, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law & Justice, UNSW Sydney, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.