Why the collapse of FTX is worse than Enron

FTX was the second largest cryptocurrency exchange in the world – today it has been named ‘a complete failure of corporate controls’. What happened? Associate Professor Mark Humphery-Jenner explains.

FTX was the second largest cryptocurrency exchange in the world – today it has been named ‘a complete failure of corporate controls’. What happened? Associate Professor Mark Humphery-Jenner explains.

Victoria Ticha

+61 2 9065 1744

v.ticha@unsw.edu.au

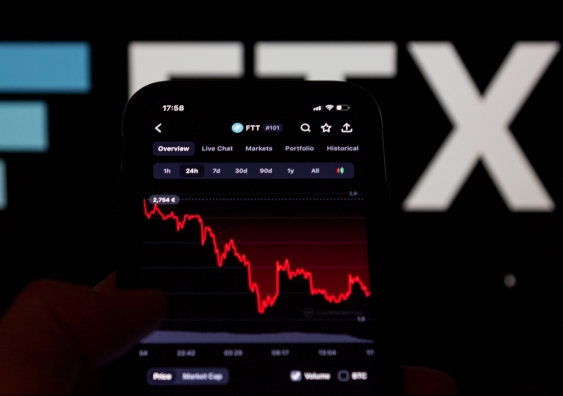

Until recently, cryptocurrency exchange FTX was the second largest crypto exchange in the world, after Binance. It had risen to prominence with support from major investors, such as Sequoia, BlackRock, Temasek, and OTPP. At one time, it was worth $32 billion and spruiked by celebrities, such as footballer Tom Brady. FTX’s then CEO was the second largest donor to the democrats.

Today FTX has entered bankruptcy with users of the exchange set to lose large amounts of money. A new CEO to oversee the bankruptcy process. Ironically, that CEO is John J Ray III, who also oversaw Enron’s bankruptcy proceedings.

Enron is often seen as the gold standard for corporate fraud, malfeasance, and complacency, with the scandal leading to the largest bankruptcy reorganisation so far in U.S. history.

The Enron scandal triggered a wave of regulatory reform, culminating in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and changes to the NYSE and NASDAQ listing rules.

In the bankruptcy petition for FTX over the FTX collapse, the new CEO shredded FTX, Alameda, and FTX’s former management team. Tellingly, he states:

“Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here”

A digital or virtual currency that is secured by cryptography. Many cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Dogecoin and UltraCoin (UTC) and are decentralized networks based on blockchain technology, hosted on blockchain platforms such as Solana.

What is a crypto exchange?

A cryptocurrency exchange is a platform for buying and selling cryptocurrencies. Examples include Binance, Coinbase and FTX.

This came from the CEO who oversaw Enron’s bankruptcy.

And it gets worse. It has been revealed that the former CEO (Sam Bankman-Fried, or SBF for short) treated FTX as a ‘personal fiefdom’. FTX money seemed to go to buy property in individuals’ personal names. This involves at least 19 properties in the Bahamas – where FTX is headquartered – worth at least $121 million.

And the contagion has spread. Indeed, even Australian entities – such as Digital Surge – are impacted, having to pause withdrawals. Celebrities are under scrutiny for promoting FTX, and CEOs, like billionaire Elon Musk, are coming out of the woodwork to tell us they knew all along.

UNSW Business School's Associate Professor Mark Humphery-Jenner says the problem isn't with crypto, the problem is corporate governance. Photo: Supplied

FTX has indeed had poor risk management and internal controls. The petition merely touches the tip of the iceberg. Here are some ey highlights (or lowlights).

The problems with FTX are myriad. The bankruptcy petition noted – in several places – that the accounts were not reliable. The filing specifically states, “The FTX Group did not keep appropriate books and records, or security controls”.

Alameda Research (an entity closely tied to FTX and majority owned by SBF), the filing states, “I do not have confidence in it, and the information therein may not be correct as of the date stated” … “[Alameda] did not keep complete books and records of their investments and activities”.

The cash management issues were seemingly broad-based. “The FTX Group did not maintain centralised control of its cash. Cash management procedural failures included the absence of an accurate list of bank accounts”. It is not clear how FTX could operate as a going concern without even being aware of what bank accounts it has.

It should be no surprise then that FTX’s cash was seemingly used to buy property that “was recorded in the personal name of these employees” and for which there was no documented loan. It raises the concern that executives treated FTX as a private piggy bank.

Not only that, FTX and Alameda appear to have been incompetent. They appear to have lost money in the crypto bull market before 2022. This alone should have promoted more attention to appropriate risk management.

Much of the regulatory discussion has focused on crypto. Must it be regulated? How so? Should we just burn crypto assets and crypto markets to the ground and replace it with central bank digital currencies?

The problem, however, is not with crypto. The problem is corporate governance: We did not learn the lessons from two decades ago.

After Enron, regulations changed to require companies to rotate auditors, have an independent audit committee, and have a majority independent board of directors. These only apply to listed companies, not unlisted ones. These changes impose some costs on small companies, but, there are major benefits. Especially when that company has custody of other people's money and has raised billions of dollars from investors.

SBF is ‘overconfident’ by his own admission. Sequoia – a major VC fund that put hundreds of millions into FTX – described FTX as having a “saviour complex”. Overconfident CEOs are significantly more likely to have accounting irregularities, resulting in litigation.

Better governance could have solved this situation. FTX might still exist if outside investors had imposed more discipline on FTX, required adequate internal controls, and properly audited financial reports.

Board independence does restrain overconfident CEOs, of which SBF is one by his own admission. It exposes underperforming CEOs to disciplinary action and firing. This even seems to be the case where the CEO might otherwise be entrenched. The problem is that FTX had none of these internal controls. Indeed, corporate control was “in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals”, according to the bankruptcy filing.

Read more: What will Australian regulation mean for cryptocurrency?

Regulators are right to be concerned. FTX’s fall has triggered contagion and the spectre of more crypto bankruptcies, ranging from Voyager to BlockFi to FTX. The contagion imposes significant financial costs on innocent ordinary investors, institutional investors, employees, and other counterparties.

The problem with simply doing “more” regulation is that crypto is not to blame for low-quality, complacent, inexperienced executives. Crypto is not to blame for the alleged misuse of customer funds. Crypto is not to blame for shoddy accounting.

The hope is that regulators can be fully educated about crypto and decentralised finance. This can involve requiring crypto “exchanges” to operate within broadly analogous frameworks to traditional brokers. It can require properly audited books and a technically competent senior management team.

Suggested reforms include prohibiting exchanges from using their own coins as collateral, requiring them to separately itemise said coins in their books, forcing proper risk management, prohibiting unauthorised use of customers’ funds, and requiring proof of reserves.

The situation is complex, however. FTX was headquartered in the Bahamas. Crypto operates across borders. And, ultimately, given that regulations only have so much reach, consumer education will ultimately be increasingly necessary.

Mark Humphery-Jenner, Associate Professor School of Banking and Finance, UNSW Business School, can be contacted for comment on the above at m.humpheryjenner@unsw.edu.au.