Beyond Black Friday: how much waste ends up in landfill?

While bargain sales pump out assets destined for the dump, emerging recycling technologies offer sustainable solutions to landfills.

While bargain sales pump out assets destined for the dump, emerging recycling technologies offer sustainable solutions to landfills.

Victoria Ticha

+61 2 9065 1744

v.ticha@unsw.edu.au

Black Friday, Cyber Monday and Boxing Day sales all have one thing in common. The pursuit of extracting money from consumers creates an incredible amount of waste. And when faced with all of the deals, bargains and discounts, it’s easy for consumers to forget about the environmental impact as they click ‘purchase’.

But is it fair to blame consumers for this waste when the economy is set to reward this kind of behaviour, and there has been an apparent lack of effort to come up with sustainable solutions for managing the subsequent waste?

In Australia, our current waste management and waste disposal systems aren’t as sustainable as touted. So, what's the role of government and business in driving sustainable solutions to waste and recycling today? We asked a UNSW academic and a UNSW Business alumnus for their insights.

A landfill commonly referred to as a tip, rubbish dump, or dumping ground, is a site where waste material is disposed of by filling a giant hole in the ground with, you guessed it, your rubbish. It is the oldest and most common method of disposing of waste, which some say is not sustainable. Landfills can turn into low-oxygen environments, where matter is converted to methane when it decomposes. Methane is a very powerful greenhouse gas that is driving climate change, opens in a new window.

Most people in Australia are aware of the yellow lid bin: unlike the red lid bin for general waste, it is for loose container recyclables, including aluminium and steel cans, glass bottles and jars. While you might think that what’s in your yellow bin collection is being sorted and recycled, this isn’t always the case.

The National Waste Report 2020 shows that Australia’s waste has increased to 74 million tonnes yearly. More than 40 per cent of all waste is sent straight to landfills. Alarmingly, figures from the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics analysis show that 84 per cent of all plastic, opens in a new window is sent straight to landfills.

The fact that Australia still fails to reuse much of the material sent to landfills has dire consequences for the sustainability of people and the planet.

And the above figures show only what’s being reported. Of the 60 per cent of all waste that is “estimated” to be recycled, experts say that a lot of it is not recycled and instead sits in stockpiles. For example, millions of plastic bags and other soft single-use plastic items dropped off by customers at Coles and Woolworths have been stockpiled in warehouses and not recycled, which – as well as misleading the public – poses potential environmental and fire safety risks.

This is also below the national resource recovery target of 80 per cent by 2030, which was set in the 2019 National Waste Policy Action Plan.

Australia’s new waste export bans, opens in a new window are expected to reduce the current rate of recycling. In addition, Infrastructure Australia recently found, opens in a new window that constraints on collecting and processing recyclable waste, including product design and low demand, have led to recyclable waste ending in landfills.

Perhaps Australia’s reliance on sending waste overseas, opens in a new window for recycling has fuelled a crisis in the industry, which is unable to cope with the levels of waste that exist in Australia. So the verdict is in: Australia must revolutionise recycling and reuse what materials it can. And, thanks to those working tirelessly to develop innovative solutions for landfills, this is something to be hopeful about.

Read more: State of the climate: what Australians need to know about major new report

Amid the tonnes of household waste sent to landfill are valuable materials that have the potential to be transformed into brand-new products, reduce emissions, and help humans address the pressing threat of climate change, says ARC Laureate Fellow Scientia Professor Veena Sahajwalla, opens in a new window, who heads the team at the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) at UNSW Sydney, opens in a new window.

Founded in 2008 by Prof. Sahajwalla, the SMaRT Centre works with industry, national and international research partners, and governments across Australia to develop innovative environmental solutions for the world’s biggest waste challenges.

For example, they have developed MICROfactorieTM technologies, opens in a new window that transform problematic waste materials, such as glass, textiles and plastics, into new value-added materials and products, such as engineered green ceramics for the built environment and plastic filament as a ‘renewable resource’ for 3D printing.

Prof. Sahajwalla and her team at the UNSW SMaRT Centre are passionate about ‘mining’ overburdened landfills and reclaiming the wealth of materials embedded in waste. Prof. Sahajwalla and her team are working closely with industry partners to develop processes and technologies that will direct some of the world’s most challenging waste streams away from landfills and back into production.

Recycling not only brings obvious benefits to society but also delivers reduced energy needs and environmental impacts by overcoming the energy-intensive extraction and processing required of natural resources, says Prof. Sahajwalla.

There is no such thing as ‘waste’, she says. Instead of seeing waste as something to dump and forget, there is a world of opportunity to turn waste into recycled products. This is the belief in the world of material science, where the idea of a used can, a discarded tyre or a smashed iPhone is a gateway to an untapped world of ‘new’ recycled products, she says.

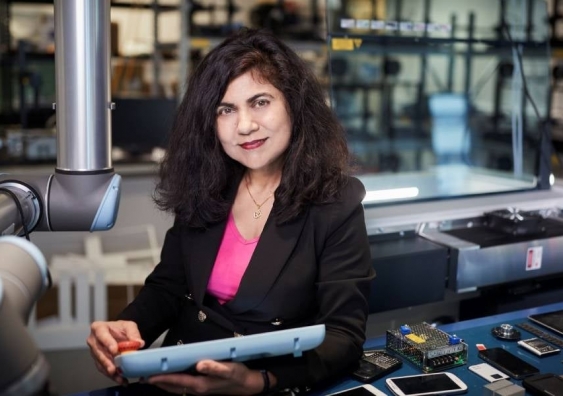

UNSW Sydney's Scientia Professor Veena Sahajwalla is working with industry partners to develop processes and technologies that will direct waste from landfills and back into production. Photo: Supplied

And this also poses a huge business opportunity. For example, the 2021 E-product Stewardship in Australia Evidence Report, opens in a new window commissioned by the Australian Department of Environment found “no single source of truth” in Australia regarding e-waste. The report also found around half of all e-waste in Australia goes to landfill each year, representing an estimated loss of value of $680 million.

There are also other opportunities, like how we clean up solid waste, which includes hazardous waste.

But it’s not just households that produce waste; most is actually produced by the construction industry, opens in a new window. Typical construction waste products include Insulation and asbestos materials, concrete, bricks, tiles and ceramics, wood, glass, and plastic. Much of this waste, about 20 million tonnes a year, opens in a new window, end up in landfill. All of these provide new opportunities to reuse waste going to landfills.

Read more: UNSW waste pioneer recognised with Clunies Ross Innovation Award

According to Andrew Douglas, Founder and Director of Kandui Technologies and Managing Director of Mattress Recycle Australia, much of the waste going to landfills is recyclable.

Mr Douglas is one of the industry partners working with the UNSW SMaRT Centre to utilise innovative solutions to waste. As a graduate of an MBAX (Social Impact) at AGSM @ UNSW Business School, opens in a new window, UNSW Sydney, Mr Douglas founded Kandui Technologies to license SMaRT’s Plastics and Green Ceramics MICROfactorieTM Technologies, opens in a new window commercially.

The venture aims to reuse difficult-to-recycle materials and remanufacture them into highly engineered and valued products while advancing Australian manufacturing capability.

“Over 10 years ago, I presented at a sustainability workshop in Wollongong. I was talking about the work we were doing recycling mattresses, and I spoke of the challenges of reusing textiles that had been glued and combined with other materials. Veena and I chatted after the presentation, and she mentioned their work at the Uni. They had a research project looking to solve the problem I had experienced, so we became an industry partner to the UNSW SMaRT Centre,” he says.

The idea to start Kandui Technologies was also born then.

“With my background in sustainability and social impact, I wanted to start a company that could commercialise the great work that Veena and her team at the SMaRT Centre were doing,” he says.

“I could see a pathway to bringing the products (made predominantly from waste) to market. Many people told me the idea wasn’t feasible and waste on high-value products was a no-can-do-it proposition. Kandui was borne from the premise that we can do it.”

And there are still plenty of opportunities to use household and industrial waste to create innovative solutions that help people and the planet. “Our business model is to take low-value materials like waste glass, textiles and plastics as manufacturing inputs. We then apply the science that has been developed at UNSW Sydney to make high-performing and high-value Australian products such as tiles, benchtops and 3D printed components,” he says.

And is this paying off?

“The demand for our products is so overwhelming we have had to scale our manufacturing capability by 90 per cent to keep up,” he says.

Read more: Why are insurance costs going up right now?

The federal government has set a target to recycle or reuse 100 per cent of plastic waste by 2040, opens in a new window and end plastic pollution. It is also investing $250 million into new and upgraded waste facilities and recycling services through the $1 billion promised in the Recycling Modernisation Fund (RMF), opens in a new window, with contributions from the states, territories, and industry. But is it enough?

As taxpayers, Australians expect the government and local councils to deal with waste adequately; it seems like an essential requirement for society. Yet even major supermarkets, like Coles and Woolworths, are struggling with their waste collection and recycling efforts. What’s the challenge?

“The centralisation of recycling facilities makes the cost of recovering materials more expensive for regional and remote communities. The MICROfactorieTM concept is to de-aggregate the recycling locations to the sources of waste in these areas and adapt them to the types of waste being generated,” explains Mr Douglas. And the thought of reversing the current status quo to benefit these communities is what appeals to him.

Whose responsibility is it to solve Australia’s addiction to landfills? While the problem can’t be blamed on consumers, everyone can play a role in tackling waste.

As Mr Douglas explains: “Governments can set the policy framework, provide funding and incentives and mandate the procurement of recycled materials. Companies can look at their own supply chains to identify where materials manufactured from waste can be substituted and where their current waste goes.

“And individuals can also drive the uptake in products made from recycled content by being informed about what their goods are made from.”

(Find out more detailed information about how and what can be recycled, opens in a new window.)

And while the problem may seem overwhelming, people can take some comfort that there are some advanced recycling initiatives in the works, people who are working tirelessly to find solutions for the most difficult-to-recycle waste streams.

“Engineering the waste materials to perform a higher function than when they were first manufactured allows the economics to stack up. This has been missing from our pivot away from landfills as a waste solution,” concludes Mr Douglas.

So as Christmas Day and more sales fast approach, remember to reuse, recycle, and reduce what you can, urge federal and local governments to act, and support research and business initiatives that are tackling the war on waste head-on. This space is ripe for new innovation and investment.