Southern Ocean takes on the heat of climate change

New modelling shows the Southern Ocean to have absorbed the majority of excess greenhouse-related warming due its unique geographic properties.

New modelling shows the Southern Ocean to have absorbed the majority of excess greenhouse-related warming due its unique geographic properties.

Jesse Hawley

0422537392

jesse.hawley@unsw.edu.au

Of all the oceans on earth, the Southern Ocean does the lion’s share at slowing the pace of climate change by absorbing most of the excess heat trapped in the planet’s atmosphere, say scientists from the ARC Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS) at UNSW Sydney.

In the past 50 years, the oceans have absorbed more than 90 per cent of the excess heat caused by carbon dioxide emissions, with one ocean absorbing the vast majority.

“The Southern Ocean dominates this ocean heat uptake, due in part to the geographic set-up of the region,” said UNSW PhD candidate Maurice Huguenin, the lead author of a new study published in Nature Communications.

“Antarctica, which is surrounded by the Southern Ocean, is also surrounded by strong westerly winds,” Mr Huguenin said.

“These winds influence how the waters absorb heat, and around Antarctica they can exert this influence while remaining uninterrupted by land masses – this is key to the Southern Ocean being responsible for pretty much all of the net global ocean heat uptake,” he said.

Mr Huguenin said that these winds blow over what is effectively an infinite distance – cycling uninterrupted at southern latitudes – which continuously draws cold water masses to the surface. The waters are pushed northward, readily absorbing vast quantities of heat from the atmosphere, before sinking into the ocean’s interior at around 45°S, north of the eastward flowing Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

But, while ocean warming helps slow the pace of climate change, it is not without cost, said co-author Professor Matthew England at UNSW Science and Deputy Director of ACEAS at UNSW.

“Sea levels are rising, ice is melting, ecosystems are experiencing unprecedented heat stress, and the frequency of extreme weather events is increasing,” Prof. England said.

Mr Huguenin said we still have a lot to learn about ocean warming beyond the previous 50 years highlighted in the study.

“All future projections, including even the most optimistic scenario of 1.5°C global warming, predict even warmer oceans in the future.

“If the Southern Ocean continues to account for the vast majority of heat uptake until 2100, we might see its warmth increase by up to seven times more than what we have already seen up to today.”

Prof. England said this will have an enormous impact around the globe including disturbances to the Southern Ocean food web, the melting of Antarctic ice shelves and changes in the conveyor belt of ocean currents.

The scientists used a novel experimental approach to find exactly where excess heat is taken up by the oceans and where it ends up after absorption. This was previously difficult to detect as observational records were not only sparse, but only began recently.

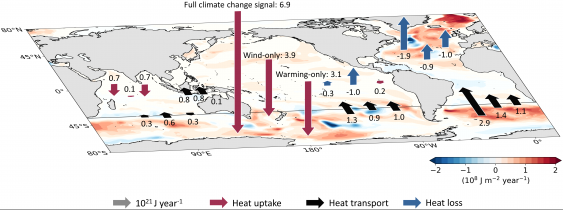

The team ran a model with atmospheric conditions fixed in the 1960s – prior to any significant human-caused climate change. They compared this model to others in which the oceans experience the past 50 years of climate change using actual observational data. The results showed that the Southern Ocean is the most important absorber of greenhouse gas-trapped heat and that it’s ocean circulation – driven by wind – that forces excess heat into the ocean interior.

Global ocean heat uptake, heat loss and heat transport over the last half century, run through different historical simulations. The red and blue vertical arrows indicate heat gain and loss in each basin. The black (slanted) arrows show the heat transport rates. Figure: Maurice Huguenin, 2022.

To better understand how Southern Ocean heat uptake continues to evolve, the scientists call for ongoing monitoring of this remote ocean – including installing additional deep-reaching Argo floats, which are pivotal for tracking ocean heat content. They also stress the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“The less carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere, the less ocean change we will lock in,” the authors said.

“This can limit the level of adaptation required by the billions of people living near the ocean by minimising the detrimental impacts of ocean warming on their primary food source.”