Road injuries are killing young people, and it's hardly slowing down

Traffic and unintentional injuries are the leading cause of adolescent deaths worldwide.

Traffic and unintentional injuries are the leading cause of adolescent deaths worldwide.

Ben Knight

UNSW Media & Content

(02) 9065 4915

b.knight@unsw.edu.au

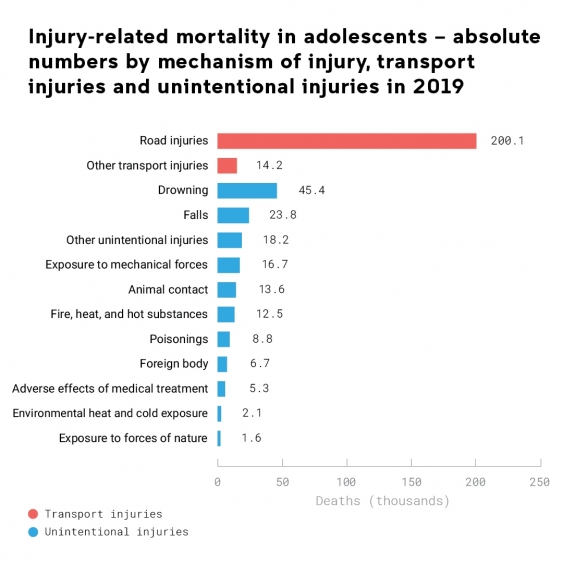

New research led by UNSW Sydney reveals traffic-related fatalities and injuries are the biggest killers of young people worldwide – causing more deaths than communicable and non-communicable diseases or self-harm. The findings are published today, opens in a new window in The Lancet Public Health in the first global analysis of transport and unintended injury-related morbidity and mortality of young people aged 10-24.

Using the latest data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 Study, the researchers analysed deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) from transport and unintentional injuries in adolescents across 204 countries in the past three decades. They found that despite transport injury death rates falling by a third since 1990, the number of deaths attributed to road fatalities for adolescents still increased in some countries.

“We’ve seen a high increase in the absolute number of injury-related deaths and DALYs, specifically in low and low-middle income countries. It indicates neglect for a growing population at risk of injury,” says lead author Dr Amy Peden, a research fellow with the School of Population Health at UNSW Medicine & Health.

According to the research, reductions in transport injury death rates in high-income countries have slowed in the most recent decade. They dropped just 1.7 per cent a year between 2010 and 2019 compared to the fall of 2.4 per cent a year between 1990 and 2010.

“In high-income countries like Australia, there’s been a real decline in progress. In the past 10 years, we’ve seen reductions in rates of road transport injury essentially stall, showing a lack of attention to the issue,” Dr Peden says.

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to injury risk due to increasing independence and risk-taking tendencies. However, there has been little research to date that has examined injury patterns in this vulnerable age group.

As other causes of mortality in young adults get more focus, Dr Peden says the lack of progress in reducing transport injury deaths only becomes more apparent.

“Despite being the leading cause of death in adolescents globally, it’s been relatively neglected when you consider the strong action on other non-injury causes of death among adolescents,” Dr Peden says.

There is also a growing burden of transport injuries in low-income countries, where the proportion of deaths almost doubled from 28 per cent in 1990 (74,713 of 271,772) to 47 per cent in 2019 (100,102 of 214,337).

‘There are simple, affordable and proven interventions to reduce road traffic injuries that are not being applied or enforced.’

Dr Peden says the shift in the burden of transport injury toward lower-income countries needs urgent assistance from the global community.

“Low socio-demographic index (SDI) countries are dealing with the challenges that come with rapid urbanisation, and as such, young people are at a greater risk of road traffic and other types of injury,” Dr Peden says.

Transport and unintentional injuries are the biggest killers of young people. Image: UNSW Sydney.

Making roads safer doesn’t necessarily require radical solutions, Dr Peden says. It just needs a stronger commitment globally to promote safety behaviours.

“The prevention of road traffic injury is still not very well resourced compared to other causes of death of adolescents. So, the findings show a lack of investment in the issue from the global health community,” Dr Peden says.

Graduated driver licensing, minimum drinking age laws, lower blood alcohol content levels for novice drivers, seat belt and helmet laws, and school zones have all shown to be effective in reducing injury-related harms when imposed. All-age interventions such as speed enforcement and drink driving enforcement are also effective in reducing road traffic deaths and should have increased focus, Dr Peden says.

The research also recommends promoting active transport infrastructure to prioritise alternative travel options and designing streets with the road safety needs of children and adolescents at the forefront of the planning.

“There are simple, affordable and proven interventions to reduce road traffic injuries that are not being applied or enforced,” Dr Peden says. “Now is the time to step up global action on road safety and renew our efforts to safeguard adolescents from preventable injury.”

The United Nations General Assembly is convening a high-level meeting on improving global road safety this month, focusing on investment in road safety.

“We have ambitious but necessary targets set out in the Decade for Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, opens in a new window to prevent at least 50 per cent of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030,” says Professor Rebecca Ivers, Head of UNSW School of Population Health and a co-author of the paper.

“What we need now is the political will for change, backed by measurable action, financial support and the right mechanisms to implement solutions, especially in communities where the burden of road traffic injuries is greatest. This week’s high-level meeting is an important step to give road safety the attention that’s needed so we can save lives,” Professor Ivers says.

“This entirely preventable public health issue does not occur in silos – having safe transport systems is also directly linked to the kind of inter-sectoral action that can lead to sustainable cities and communities and to mitigate the impact of the climate crisis.”

The next stage of the research will investigate the economic case for governments to invest in injury prevention interventions for adolescents and policy change worldwide, Dr Peden says.

The study was co-authored by Dr Patricia Cullen, Dr Holger Möller and Professor Rebecca Ivers from the School of Population Health and forms part of the injury workstream of the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence: Driving Global Investment in Adolescent Health.