He almost became a farmer in Iceland. Now, he's leading RNA development in Australia

UNSW Sydney professor Pall Thordarson shares the chemical reaction that took him from working on a farm in Iceland to running the first RNA institute in Australia.

UNSW Sydney professor Pall Thordarson shares the chemical reaction that took him from working on a farm in Iceland to running the first RNA institute in Australia.

Ben Knight

UNSW Media & Content

(02) 9065 4915

b.knight@unsw.edu.au

Professor Pall (Palli) Thordarson, an award-winning researcher and chemistry professor at UNSW Science, almost didn’t become a scientist.

In fact, the professor – who was recently named the head of the UNSW RNA Institute – almost didn’t go to university at all.

“I had a tough time deciding whether I wanted to be a farmer or go to university,” says Palli.

“It was a really hard decision. I took a year off to work on the farm and think about it.”

It’s no wonder Palli found this decision so hard – the farm life had been in his veins ever since he was born.

The mountain overlooking Palli's family farm, where he'd spend time watching birds migrate and finding different types of plants and flowers. Photo: Marie Th. Robin.

Palli grew up on his family’s sheep and dairy farm nestled at the foot of a mountain in Vopnafjörður, Iceland.

His hometown was small – there were around 10 other kids in his class growing up – and the nearest town was still a two-hour drive away. During the harsh winters, these roads out of town closed, and the only way to leave was via aeroplane.

But it was on this secluded farm where Palli’s love of science was ignited.

Young Palli loved watching Carl Sagan’s Cosmos and the early David Attenborough documentaries. Photo: Pall Thordarson.

“I was fascinated by nature from day one,” says Palli. “It was easy on a farm. A love for science and nature came naturally to me.

“My brother and grandmother taught me how to recognise the different types of plants and flowers and different types of birds. We’d especially love watching the birds migrate.”

Science didn’t end on the farm, though: when teenage Palli wasn’t busy helping out, he spent time watching Carl Sagan’s Cosmos and the early David Attenborough documentaries.

Watching these documentaries and spending time in nature helped fill Palli’s science cup – for a while. But as Palli grew older, there was more he wanted to learn, and it wasn’t possible to stay on the farm and travel to university at the same time.

When the time came to make a call between the two, he decided to say goodbye to the farm and pack his bags for university.

After that big decision, Palli faced his next big choice: deciding what to study.

Chemistry came naturally to Palli in school, with his love of the outdoors steering him towards specialising in biochemistry. But he was also tossing up between a career in physics and geology.

Despite these pulls in different directions (at one point, he even considered studying Icelandic literature), Palli found himself being drawn back to chemistry.

“At the core, I’m an organic chemist,” says Palli. “But I've been interested in the interface between chemistry and biology ever since my undergrad days.”

After finishing his chemistry degree in Iceland, Palli travelled to Sydney for his PhD degree.

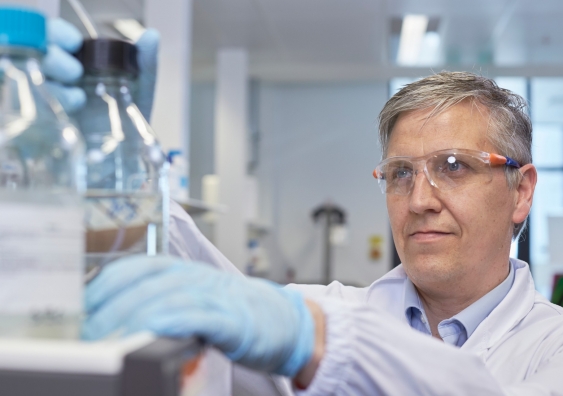

Palli has been fascinated by RNA ever since his PhD days. Photo: Pall Thordarson.

He was here in Australia researching self-replicating molecules when he first came face-to-face with RNA: a molecule similar to DNA that helps keep our bodies running smoothly.

He had no idea at the time just how big a role RNA would play in his future career.

“I've been fascinated by RNA since my PhD days,” says Palli. “I always wanted to work with RNA.

“I remember looking at RNA and RNA-based systems biology as a PhD student and thinking, ‘These are the most fascinating chemical machines in the world’.”

One of RNA’s important jobs is to instruct our cells to make proteins. A certain type of RNA, called messenger RNA or mRNA, acts as a chemical messenger from the DNA to the protein-producing factories in our cells. In other words, RNA is like the software that keeps our hardware – that is, our cells – running smoothly.

But scientists are constantly learning more about RNA and what this molecule is capable of.

“The old view was that the main role of RNA was just as some sort of middleman, a messenger, between the DNA and the proteins that are made in our cells,” says Palli. “But that's only a small fraction of the importance of RNA in biology.

“A lot of DNA is transcribed into what's called non-coding RNA, which has a lot of other functions. We're still only realising what all of these functions are, but it seems like RNA is really important in organising the cell structure and cell function in many other ways.”

Even though it would be years before Palli came back to studying RNA, this molecule would soon not only change the direction of his work – but also play a key role in helping the world fight COVID-19.

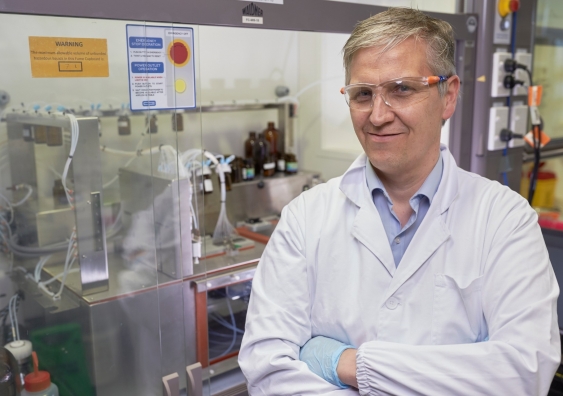

Palli says kickstarting NSW's RNA capabilities is his short-term goal for the UNSW RNA Institute. In the long term, he wants to focus on breakthrough science. Photo: UNSW Sydney.

Twenty years after Palli’s first brush with RNA, he now heads the UNSW RNA Institute, the first RNA-focused institute in Australia.

The recently-launched institute brings together experts from UNSW Science, Engineering and Medicine & Health faculties to collaborate on RNA research.

“We have quite a few chemists, biologists, engineers, and medical researchers involved in our institute,” says Palli. “This breadth of expertise is unique and gives us an exciting opportunity.

“In the short term, our goal at the institute is to kickstart RNA capabilities here in NSW. In the long term, we are absolutely focused on breakthrough science.”

In addition to this role, Palli is also leading the NSW RNA Bioscience Alliance – an alliance between NSW and ACT universities to advance the research, development and manufacturing of RNA technologies.

The alliance is working with the NSW Government to use a $96 million government grant to create a first-of-its-kind pilot manufacturing facility to translate mRNA and RNA research into home-grown therapies and vaccines.

While many vaccines traditionally contain a weakened or dead version of a virus, mRNA vaccines – such as Pfizer and Moderna – instead use mRNA molecules coated in protective shells.

“In the short term, our goal at the institute is to kickstart RNA capabilities here in NSW. In the long term, we are absolutely focused on breakthrough science.”

Once the vaccine enters the body, the mRNA instructs the cells how to make copies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, in turn training the body how to recognise and attack the virus before it ever comes face-to-face with the real thing.

“The science behind mRNA vaccines has been bubbling away for the past 10 or 20 years, but this is the first time we’ve really deployed it,” says Palli.

“It's been a game changer for the world to have those two vaccines.”

mRNA’s ability to create vaccines has been the star of the RNA show during COVID-19. But Palli says the future possibilities of RNA technologies are even more mind-boggling.

“We are only just scratching the surface of RNA technology and mRNA vaccines are only the tip of the iceberg,” he says. “We have so much more to learn about RNA, like its role in cellular organisation and how it’s linked to brain development.

“By understanding how RNA functions and being able to manipulate RNA, we could one day potentially use the technology to help us treat neurodegenerative diseases and other developmental-related conditions.”

Palli often thinks back to lessons he learnt on the family farm and find they still help him today. Photo: Pall Thordarson.

Nearly 30 years after leaving the farm in Iceland, Palli is now very settled into life in Australia. He moved to the Southern Highlands, where he now lives with his wife, two kids, cat and dog.

While he misses his childhood family farm – which is still thriving to this day – he often thinks back to lessons he learnt there and finds they still help him today.

“You need to learn persistence and patience when working on the farm,” says Palli. “You put the fertiliser on your fields in spring, which becomes hay in summer. You’ll then use the hay to feed the sheep over the next winter, who’ll have their lambs the following spring.

“That might be why academic research feels so similar to me. You can start with a rich idea, but it can actually be two years or more until you have a publication.

“You need that patience and persistence in academia – and you need the two of them, together.”

An academic career in Australia wasn’t where young Palli in Iceland saw himself heading – in fact, applying to study in Australia was a spur-of-the-moment decision, and he didn’t consider becoming an academic until halfway through his PhD.

“You need that patience and persistence in academia – and you need the two of them, together.”

Now, when asked what advice he would give young scientists, Palli says it’s so important to stay open minded about the future.

“The best advice I can give you, wherever you are on your journey, is to be open minded,” he says. “What you think you're going to do next might not actually be what will happen next, and that’s OK. We need scientifically educated people in all sorts of careers.

“It’s important to network, be a team player, and keep your options and eyes open. You never know where the future will take you. If you accept that, your persistence in advancing whatever you are working on at any given time is often the ticket to (unexpected) success.”