How machine learning can clean up our cities

Computational design can identify greater efficiencies across the built environment, enabling us to create more sustainable cities.

Computational design can identify greater efficiencies across the built environment, enabling us to create more sustainable cities.

Ben Knight

UNSW Media & Content

(02) 9065 4915

b.knight@unsw.edu.au

A new suite of design applications is in development at UNSW Sydney to help architects and urban planners optimise their designs for greater sustainability. The apps use machine learning to target the reduction of construction waste and urban heat, minimising the embedded carbon footprint of buildings.

According to lead researcher Associate Professor M. Hank Haeusler, Director of Computational Design at UNSW’s School of Built Environment, the tools will help minimise the environmental footprint of buildings by assisting built environment professionals in making more sustainable decisions around size, scale and materials.

“We’re applying a computational eye to these [today’s] global problems,” says the entrepreneur and designer. “Landfill, pollution, [the way different] materials [contribute to climate change], [as researchers] we have a moral responsibility to look into this.”

A/Prof. Haeusler works at the intersection of digital technologies, architecture and design. His expertise lies in computational design, including AI and machine learning, digital and robotic fabrication, virtual and augmented reality sensor technologies and smart cities.

In 2018-19, Australia generated an estimated 27 million tons of waste from the construction and demolition sector – 44% of the total national waste. The sector’s contribution to waste has grown by 32% per capita over the previous 13 years.

“The construction industry produces an enormous amount of waste. 10-15% of all the materials you bring onto a construction site are going straight into the bin,” says A/Prof. Haeusler.

“It’s wasteful, it’s bad for the environment, and it doesn’t align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals [that promote inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities and environmentally responsible construction].”

Additionally, Australian cities are experiencing unprecedented levels of overheating. Urban overheating arises from human activity such as waste heat from industry, cars and cooling, building with heat-absorbing materials and rapid urbanisation, and adversely affects health, energy, and the economy.

Computational design and machine learning uplift our capacity to solve these global issues, A/Prof. Haeusler says.

“In a city, there are thousands and thousands of data sets. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. Transport, urban design, economics modelling, urban heat, water, electricity – cities have super-complex systems.”

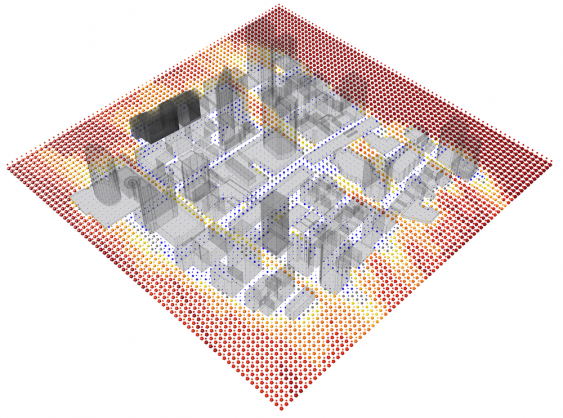

Using machine learning, the heat reduction app helps users identify design inefficiencies that can cause urban overheating. Image: Daniel Yu.

As humans, we might understand these issues in isolation. But machine learning helps us unpack the broader context and consequences of different design decisions, A/Prof. Haeusler says.

He says that machine learning can interrogate vast sets of fine-grain data in real-time to analyse and evaluate alternatives. In a design context, it can identify efficiencies and promote sustainable practices, in this case, reducing the heat and waste produced.

“[Within the UNSW heat reduction app,] you design your street and then a computer program does the calculation in the background [based on intelligence learned from its data sets. Then it tells you,] it looks like here, at this intersection, it will get hot because of the physics that shape urban heat islands.”

The designer can then adjust the building height, put in green spaces and shade, change the road width and adjust other variables to improve the building’s environmental footprint.

Similarly, the UNSW waste reduction app calculates the materials required for your design and allows you to adjust its size and scale to reduce waste offcuts. Its calculations are populated with data from public hardware sites, like Bunnings.

By translating foundational research into practical industry tools, these applications make sustainable practices more achievable, A/Prof. Haeusler says. As such, they democratise architecture and design practices, uplifting the benefits of research and development for a broader market.

“Rather than replacing cutting-edge research, their focus is on uplifting practitioners’ working knowledge to affect real-world impact.”

A/Prof. Haeusler is also working with architecture studio COX Architecture to develop research projects and promote educational opportunities for students. Giraffe Technology started as one such project, and is now a SME working in a digital architectural and property development application.

With funding from Atlassian’s Startmate accelerator program, the one-time start-up grew out of a series of research projects with staff at COX Architecture that aimed to make local (council) development data sets more accessible and facilitate feasibility studies for the city of Western Sydney.

Giraffe Technology is like a map of the world on a browser primed for architects, he says, which means anyone with access to the internet can use it. It taps into GIS mapping to populate streets, buildings, and vegetation.

Its interface is driven in the background by computer scripts that enable users to automate design processes and generate 3D architectural models. Users can conduct site analyses and calculate proofs-of-concept in real-time.

They don’t need to have any programming skills. It’s like Google, he says: it’s not necessary to understand the complicated algorithms that drive the search engine to both use and recognise its benefit.

Now an established business, Giraffe Technology is introducing an app store to house computational design tools from diverse sources. Like the app store with Apple products, apps that list on Giraffe’s platform would leverage its legal framework, data privacy and monetary systems, pain points for emerging developers, A/Prof. Haeusler says. Tools like the Waste Reduction tool or the Urban Heat Island tool will appear soon at the app store.

![use _running the giraffe] application on a mac laptop](https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/styles/full_width/public/thumbnails/image_uncropped/user_running_the_giraffe_application_on_a_mac_laptop_using_1.png?itok=cEYrTP7i)

The Giraffe platform allows for multiple users to collaborate on a single design at once, from anywhere in the world. Photo: Supplied.

A/Prof. Haeusler says computational design will only become more and more relevant, particularly with the rise of virtual representations of existing cities.

In 10 to 15 years, he predicts digital twins will become an operational part of our cities used to improve their performance, from trouble-shooting traffic issues and to investigate the feasibility of proposed developments to exploring new energy options and other planning issues.

“Cities will never be. They will always be becoming,” he says.

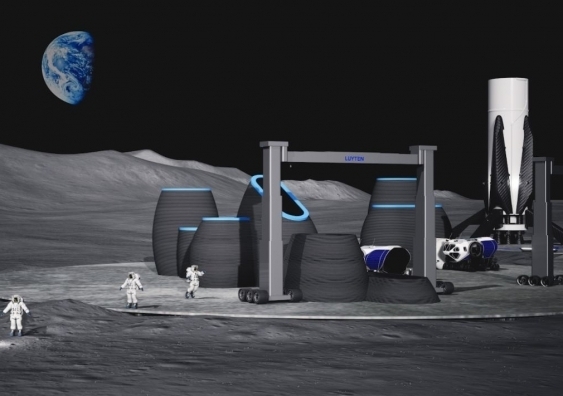

Using the power of computational design and 3D printing technology, A/Prof. Haeusler also says we’ll create settlements beyond Earth this century. In fact, his team at UNSW Computational Design recently signed a memorandum of understanding with Australian building and construction company, Luyten, to begin researching and developing a specialised 3D printer capable of building on the Moon, named Platypus Galacticas.

“With the possibilities of 3D printing, we don’t need to think about housing anymore in the traditional way,” he says. “Through computational design, we can take all kinds of scientific data, feed that into a computer program and instruct a remotely controlled 3D printer to build complex geometric structures here on Earth, and one day, the Moon.”

A/Prof. Haeusler says that doing computational design research with the Moon will have direct learnings that can be applied to challenges on Earth, like climate change and affordable housing.

“The knowledge we generate from building on the moon can be translated directly into building housing for extreme climates such as heat or for addressing housing issues in remote indigenous communities – both topics we investigate in parallel.”

A/Prof. Haeusler’s team wants to use Luyten 3D printing technology to build housing on the Moon, with a view of establishing a permanent base on the lunar surface. Photo: Luyten.