Federal Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese this week announced a commitment to funding high-speed rail between Sydney and Newcastle.

At speeds of more than 250km/h, this would cut the 150-minute journey from Sydney to Newcastle to just 45 minutes. Commuting between the two cities would be a lot more feasible.

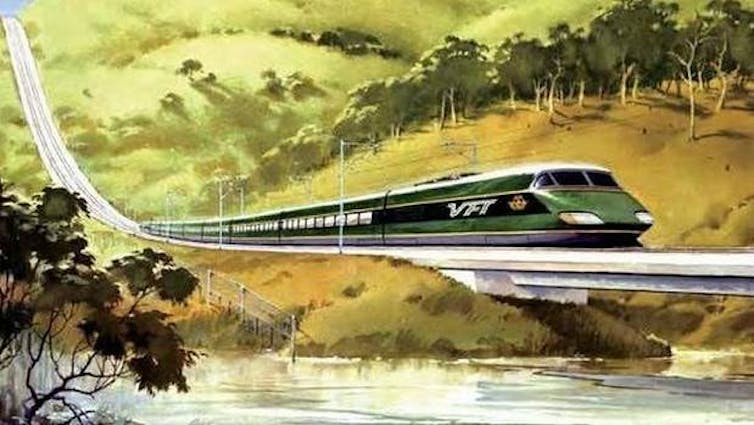

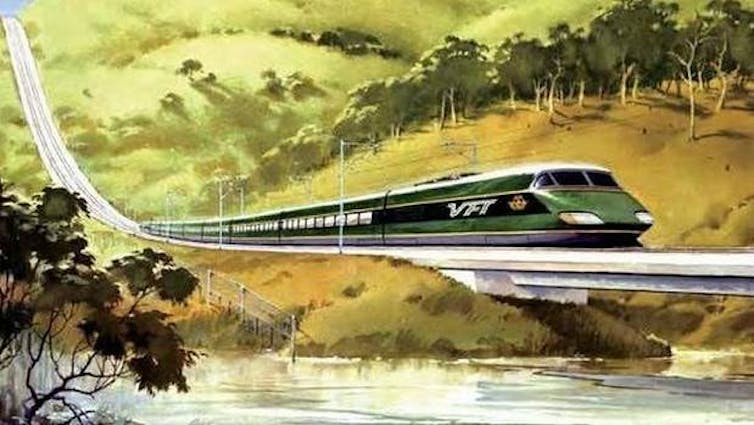

An artist’s impression of the proposed Very Fast Train in the 1980s. Photo: Comeng

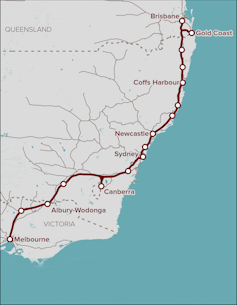

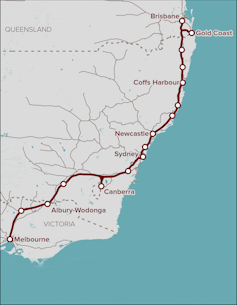

The Sydney-Newcastle link would be a first step in a grand plan to link the Melbourne-Sydney-Brisbane corridor by high-speed rail.

Albanese also wants the trains to be built at home, saying “we will look build as much of our fast and high-speed rail future in Australia as is possible”.

Of course, this idea has been around for a long time. Nobody has ever got the numbers to stack up before.

Federal infrastructure minister Paul Fletcher made the obvious but reasonable point that such a rail link would be very expensive.

“It is $200 to $300 billion on any credible estimate,” he said in response to Labor’s announcement. “It has to be paid for, and that means higher taxes”.

Or does it?

Social cost-benefit analysis

Traditional cost-benefit analysis is how governments tend to make decisions about big infrastructure projects like this. Figure out the costs (such as $300 billion) and then figure out the benefits. Adjust for timing differences and when money is spent and received, and then compare.

This generates an “internal rate of return” (IRR) on the money invested. It’s what private companies do all the time. One then compares that IRR to some reference or “hurdle” rate. For a private company that might be 12 per cent or so. For governments it is typically lower.

An obvious question this raises is: what are the benefits?

An artist’s impression by Phil Belbin of the proposed VFT (Very Fast Train) in the 1980s. Photo: Comeng

If all one is willing to count are things such as ticket fares, the numbers will almost never stack up. But that’s far too narrow a way to think about the financial benefits.

A Sydney-Newcastle high-speed rail link would cut down on travel times, help ease congestion in Sydney, ease housing affordability pressures in Sydney, improve property values along the corridor and in Newcastle, provide better access to education and jobs, and more.

The point is one has to think about the social value from government investments, not just the narrow commercial value. Alex Rosenberg, Rosalind Dixon and I provided a framework for this kind of “social return accounting” in a report published in 2018.

Newcastle might make sense, Brisbane might not

I haven’t done the social cost-benefit analysis for this rail link, but the social return being greater than the cost is quite plausible.

The other thing to remember is that the return a government should require has fallen materially in recent years. The Australian government can borrow for 10 years at just 1.78%, as opposed to well over 5 per cent before the financial crisis of 2008.

I’m less sure about the Brisbane to Melbourne idea. The cost would be dramatically higher for obvious reasons, as well as the fact that the topography en route to Brisbane is especially challenging.

Nobody is going to commute from Sydney to Brisbane by rail, and the air routes between the three capitals are well serviced.

Transport policy is not industry policy

The decision about building a Sydney-Newcastle rail link is, and should be kept, completely separate from where the trains are made. Transport policy shouldn’t be hijacked for industry policy.

To be fair, Newcastle has a long and proud history of manufacturing rolling stock, at what was the Goninan factory at Broadmeadows – much of it for export.

But ask yourself how sustainable that industry looks in Australia, absent massive government support. Can it stand on its own?

It’s also true there have been some recent high-profile procurement disasters buying overseas trains.

Sydney’s light-rail project has run massively late and over budget, with Spanish company Acciona getting an extra A$600 million due to the project being more difficult than expected.

Then cracks were found in all 12 trams for the city’s inner-west line, putting them out of service for 18 months.

These are terrible bungles due to the government agreeing to poorly written contracts with sophisticated counterparties. When contracts don’t specify contingencies there is the possibility of what economists call the “hold-up problem”.

But these problems could have occurred with a local maker too.

The Tinbergen Rule

An enduring lesson from economics is the Tinbergen Rule – named after Jan Tinbergen, winner of the first Nobel prize for economics.

This rule says for each policy challenge one requires an independent policy instrument. This can be widely applied. But here the lesson is particularly clear.

Addressing housing affordability is a good idea, and a Sydney-Newcastle link could help with that. But if Labor want a jobs policy it should develop one.

The more TAFE places Labor has already announced is a reasonable start.

Reviving 1970s-style industry policy – something that has almost never worked – is not a good move. Governments are lousy at picking winners. The public invariably ends up paying more for less, and the jobs are typically transient.

But aside from this conflation of policy goals, Albanese deserves credit for being bold about the future of high-speed rail in Australia.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.