Vital Signs: Marketing is getting in the way of markets that could get us to net-zero

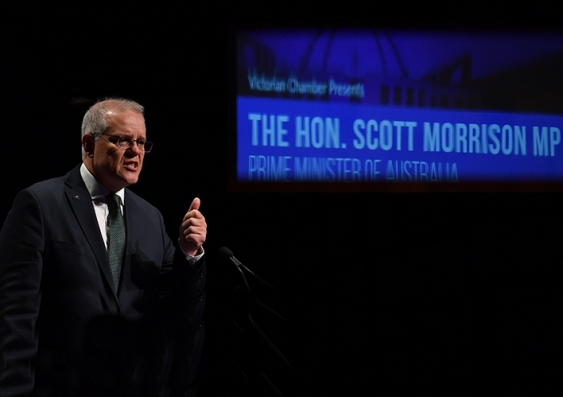

The prime minister road-tested an avalanche of slogans on Wednesday, some of them clearly false.

The prime minister road-tested an avalanche of slogans on Wednesday, some of them clearly false.

This week the prime minister entered full marketing mode.

Scott Morrison’s topic was climate change and his plans to get to net-zero.

At the Victorian Chamber of Commerce and Industry on Wednesday, he tried out a few slogans, opens in a new window.

Among those he test marketed:

can do capitalism, not ‘don’t do governments’

no one passed a law or introduced a tax or passed a resolution at the UN that led to the world developing a COVID vaccine, no one passed a law for the world to move digital, Google and Cochlear were not invented at a UN workshop or summit

Australia has already reduced our emissions by more than 20%, now, our emissions are going down, not up, they’re down by more than 20%

He said a bunch of other stuff, but those are my top three.

He wants to contrast his approach with certain United Kingdom and US environmentalists, who do indeed want to restrict what people can buy or do. Ideas like mandatory “meatless Mondays, opens in a new window” and banning advertising for SUVs, opens in a new window do indeed have no place in Australia, or even in the UK for that matter.

And nor does telling people where to drive, although the prime minister assured us he was not going to tell people “where to drive or where they can’t drive, opens in a new window”.

Economists don’t like such ideas either. The whole idea behind a price on carbon (whether through a carbon tax or a system of tradable permits) is to respect people’s preferences, while making sure their decisions take account of the costs they impose on others.

His second claim was that innovation (things like the COVID vaccine, Google search and digitisation) isn’t sparked by governments.

While it’s true that “Google and Cochlear were not invented at a UN workshop or summit”, to suggest that governments played no role is to wilfully ignore history.

The miraculous Moderna mRNA vaccine was developed… checks notes… in partnership with the US National Institutes of Health. Moderna received, opens in a new window nearly US$10 billion in taxpayer funding.

Much of the work on the Cochlear ear implant was done at the largely government-funded University of Melbourne, opens in a new window; the internet revolution grew from the US Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, opens in a new window; and Google’s search algorithm was developed by fully-funded graduate students at Stanford University, opens in a new window, whose endowment is tax exempt.

Morrison emphasised on Wednesday that Australia has reduced emissions by 20%.

It’s natural to ask what brought it about. Much of it was a cutback in land clearing, which is counted as emissions reduction under the rules. Land clearing is regulated by government, opens in a new window.

Much of the rest happened during the two years Australia had a carbon price in place, as this chart shows.

Australian emissions excluding land use, land-use change and forestry

Million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per annum, updated quarterly. Climate Council, Department of Industry, opens in a new window

The claimed 20% reduction owes much to the laws and summits the prime minister derides.

All prime ministers are politicians, so isn’t surprising they spin narratives. But to spin one so sharply at odds with reality is surprising.

When it comes to “technology not taxes, opens in a new window”, the truth is it is often taxes that drive the development and uptake of technologies.

Importantly, taxes don’t specify the particular technologies that will emerge.

Perhaps that’s why the nation’s peak body for can-do-capitalists – the Business Council of Australia – has asked the government to subject more businesses to Australia’s existing little-known (weak) price on carbon.

If we are going to get to net-zero, we’ll need less marketing and more markets. Now there’s a slogan.

![]()

Richard Holden, opens in a new window, Professor of Economics, UNSW, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.