We need herd immunity against COVID-19 vaccine misinformation

Misleading claims about COVID-19 vaccines can negatively impact public confidence in immunisation uptake, a new UNSW Sydney study reveals.

Misleading claims about COVID-19 vaccines can negatively impact public confidence in immunisation uptake, a new UNSW Sydney study reveals.

Emi Berry

Corporate Communications

0413 803 873

e.berry@unsw.edu.au

A new study published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE revealed over 103 million people globally liked, shared, retweeted or reacted with an emoji to misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 vaccines.

In 2020, a social media post claiming, “a new vaccine for COVID-19 will alter a person’s DNA and result in them becoming genetically modified” was circulated on Facebook accounts in Australia. Up until August 21, 2020, this false claim had attracted 360 shares and was viewed 32,000 times.

The study, led by UNSW researchers, examined content between December 2019 to November 2020 which included news articles, social media posts, online reports and blogs.

Associate Professor Holly Seale from UNSW Medicine & Health's School of Population Health and senior author of the study said the misinformation being shared by family members, friends and other people in the wider community network was concerning.

"From previous studies, we've been able to link this misinformation with negative outcomes, including death," explained A/Prof Seale.

Also of concern was the absence of fact-based information to counter the circulation of these conspiracy theories and rumours on multiple social media platforms, which had the potential to be misinterpreted as credible information. Additionally, the study identified numerous rumours and conspiracy theories that could negatively impact public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines and the willingness to receive the vaccination.

A national survey conducted among US adults in September 2020 on willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine found a 21 per cent decline when compared with another national survey conducted in May 2020 among similar groups. This decline could be attributable to the exposure to COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on social media.

In another study conducted among Australian adults, 24 per cent were unsure or not willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. Nine in ten (89 per cent) of these individuals were concerned about vaccine efficacy and safety, and 27 per cent did not believe a COVID-19 vaccine was necessary.

The misinformation that was examined included content ranging from vaccine development to mortality due to receiving the COVID-19 vaccination.

A post that was circulated widely claimed a Russian vaccine company omitted phase three clinical trials for a COVID-19 vaccine. This claim provoked concern and criticism from the scientific community that the vaccine was not tested for effectiveness or safety, which could result in global concern and vaccine hesitancy.

The most popular conspiracy theory circulating online was the claim that the COVID-19 vaccine could monitor the human population and take over the world. One theory proposed the COVID-19 vaccine would contain a microchip through which biometric data could be collected, and large businesses could send signals to the chips using 5G networks, thereby controlling humanity.

Negative claims about vaccine effectiveness is not a new concept. A boycott of the polio vaccine in 2004 due to claims that the vaccine caused infertility resulted in increased polio cases in Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Lead author of the study, Md Saiful Islam said rumours often challenged the health policies and interventions of government and non-government officials and international health agencies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO).

"Whether a person believes the misinformation or not is dependent on the individual’s level of health literacy and risk perceptions. However, continuous exposure to social media and online anti-vaccine movements may influence people to share and communicate vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories," said Mr Islam.

Rumours often challenged the health policies and interventions of government and international health agencies such as the World Health Organisation. Image: Shutterstock

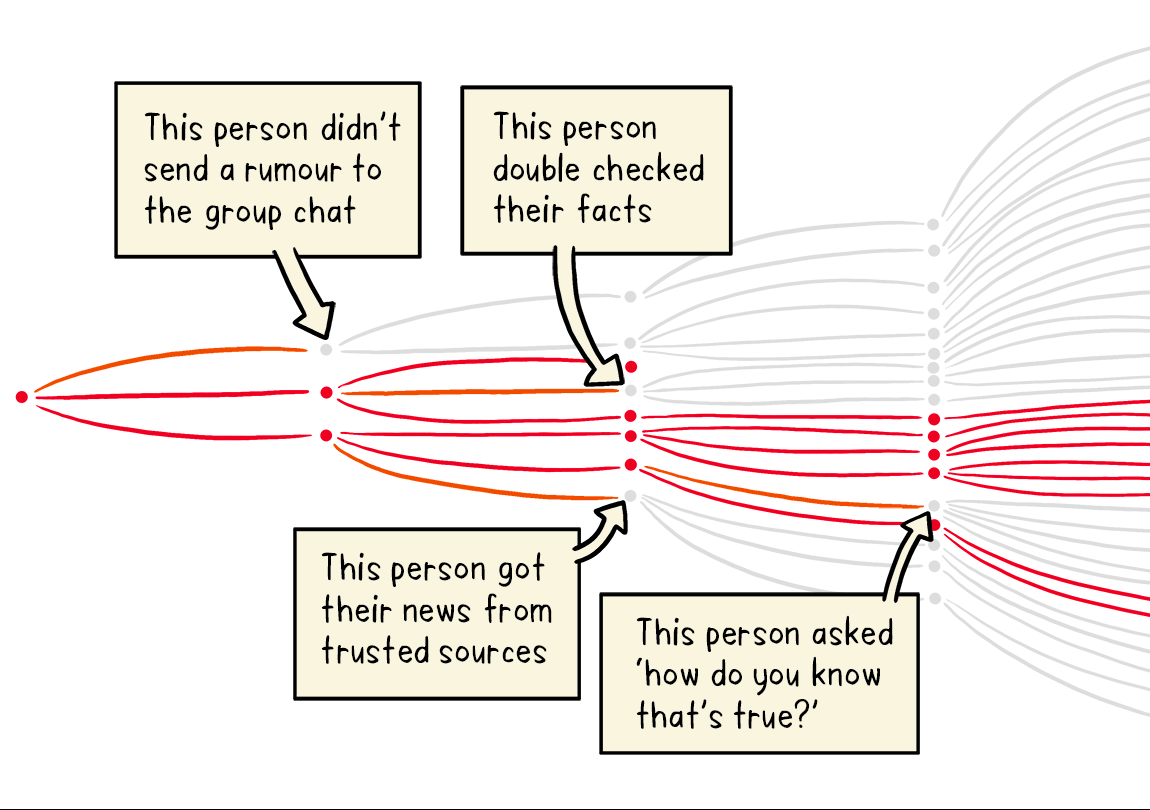

The researchers suggest herd immunity against misinformation and conspiracy theories is required to ensure herd immunity against COVID-19. It is estimated that the vaccine coverage needs to be approximately 55 per cent to 88 per cent to achieve herd immunity against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

To counter the misinformation and conspiracy theories around COVID-19 vaccines, the researchers suggest traditional methods of risk communication and community engagement. These strategies need to be explored to track and fact-check misinformation to immunise people against misinformation, pre-empting potential vaccine program disruptions.

Mr Islam said to combat the misinformation and conspiracy theories, people need to be engaged from different levels of the community.

"It's not only the responsibility of the health departments or the scientific community to debunk this misinformation, we also need to engage stakeholders such as religious leaders, school teachers, and responsible young people because it is the young people who spend most of their time on social media," said Mr Islam.

"We also need to debunk these untruths with scientific evidence. Health departments involved in vaccination rollout programs should prioritise this kind of misinformation and take action sooner rather than later. If there is a gap between detecting the misinformation and conspiracy theories to when they are debunked, the untruths could potentially reach millions of people.

"And by then it is incredibly hard to change people's perceptions once they are fed this kind of misinformation. So I think it needs to be part of a public health program and public health messaging," explained Mr Islam.

Flatten the infodemic curve. Source: World Health Organisation

Mr Islam also suggests tracking COVID-19 vaccine misinformation in real-time and engaging with social media to disseminate correct information could help safeguard the public against misinformation. He does, however, acknowledge these technologies could be expensive for low- and middle- income countries.

A/Prof Seale said the research team only analysed platforms that were open and free, which included Facebook, Twitter and other similar networks.

"But then there are the closed networks, such as WhatsApp and WeChat. We still have very little understanding about the role of misinformation, where it is originating from and what type of impact it's having, so there is a lot more research that needs to be done in this space."

The research team working on this study includes Md Saiful Islam, Abu-Hena Mostofa Kamal, Alamgir Kabir, Dorothy L Southern, Sazzad Hossain Khan, S M Murshid Hasan, Tonmoy Sarkar, Shayla Sharmin, Shiuli Das, Tuhin Roy, Md Golam Dostogir Harun, Abrar Ahmad Chughtai, Nusrat Homaira and Holly Seale.

The full research paper can be viewed here.