‘The disease of kings?’ 1 in 20 Australians get gout — here’s how to manage it

No longer just a disease of kings, the prevalence of gout is increasing around the world.

No longer just a disease of kings, the prevalence of gout is increasing around the world.

I awoke one morning late last year to find a bright red bauble at the foot of my bed. It wouldn’t have looked amiss adorning a Christmas tree. But it felt ready to explode. It was my big toe, and this was my first encounter with gout.

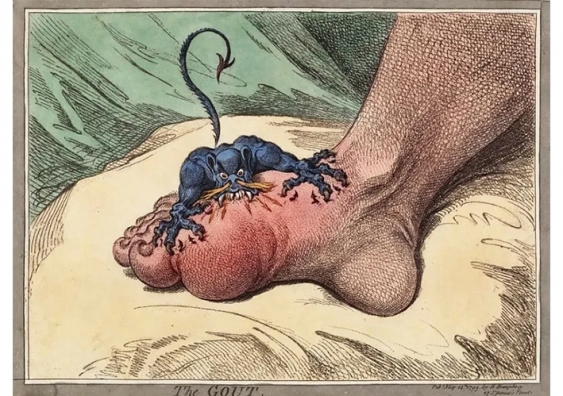

With a history, opens in a new window spanning more than 4500 years, gout is among our earliest recorded diseases. Hippocrates, traditionally regarded as the father of medicine, called it “the unwalkable disease, opens in a new window”, because it was very painful for people with gout to walk.

Many famous historical figures suffered with gout, opens in a new window, including Christopher Columbus, Henry VIII, Benjamin Franklin, opens in a new window and Beethoven. It became known as “the disease of kings”.

This moniker also reflects the fact gout has historically been associated with, opens in a new window indulging in rich food and excessive alcohol. Scientific evidence today suggests this may have something to do with it, though the common belief drinking port specifically causes gout, opens in a new window is unfounded.

Today, no longer just a disease of kings, the prevalence of gout is increasing around the world, opens in a new window. Almost one in 20 Australians have had at least one attack of gout.

And some stigma, opens in a new window still clings to the condition. Often gout is seen as being self-inflicted, a mark of overindulgence. But living with gout has far-reaching implications, opens in a new window, hampering a person’s ability to participate in everyday life.

Read more: Got gout? Here's what to eat and avoid, opens in a new window

Gout is the most common form, opens in a new window of inflammatory arthritis. It’s caused by sodium urate crystals forming in the joints. While the big toe is particularly susceptible, gout can also affect the ankles, knees, elbows, wrists and fingers.

Urate, opens in a new window, or uric acid, is an end-product of the breakdown of biochemicals called purines, which are both components of your DNA and absorbed into the body through the foods you eat. Urate levels reflect how much is made in the liver and how much is flushed out when you go to the toilet.

If your urate levels become too high, the urate turns into crystals. When urate crystals form in the fluid, opens in a new window cushioning a joint, the body’s defence forces see them as foreign invaders. Inflammation and debilitating pain follow.

Gout can be incredibly painful. Shutterstock

A high level of urate in the blood is the greatest risk factor for gout, opens in a new window. But what causes high levels of urate? While we don’t know exactly, several factors certainly contribute.

A tangled web, opens in a new window links urate, gout and other metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Being overweight, opens in a new window is a common factor.

Gout can run in families, with genetics, opens in a new window playing a key role in determining urate levels. For example, genetic differences can impair urate excretion, thereby increasing blood urate levels.

Gout is also more common in males — almost 80% of people with gout are male. One reason for this is the female sex hormone oestrogen lowers urate levels, opens in a new window, and is therefore protective against gout in pre-menopausal women.

And gout is more common the older you get, opens in a new window. It affects 0.2% of Australian men in their 20s, increasing to 11% over the age of 85, opens in a new window.

You should ice and raise the affected joint and minimise contact with it — even a light bedsheet can cause excruciating pain.

Attacks of gout can last for days or weeks. If you think you have gout, you should see your doctor.

Anti-inflammatory drugs can ease gout attacks. Your doctor might prescribe colchicine, opens in a new window, or you can get ibuprofen, opens in a new window over the counter.

It’s easy to stop exercising, opens in a new window, but swimming and cycling, opens in a new window are two ways you can comfortably continue moving during a gout flare.

Many people who have one gout attack will go on to have more. In one study, 70% of people, opens in a new window who had an attack of gout went on to have another within a year.

If you suffer two or more attacks, management of chronic gout, opens in a new window involves taking a urate-lowering therapy such as allopurinol, opens in a new window or febuxostat.

Beer is often singled out as it’s relatively purine-rich. But it’s a good idea to cut back on all types of alcohol. Shutterstock

If you’ve had gout once and want to prevent it coming back, it’s worth thinking about lifestyle changes, opens in a new window. As with other metabolic diseases, opens in a new window, losing weight, opens in a new window helps.

You might also consider minimising consumption of purine-rich foods, opens in a new window, which include meat, seafood and yeast products, like Vegemite.

But as with any diet, sticking to a low-purine diet can be challenging. Evidence for particular foods to favour or avoid for gout, opens in a new window is weak, opens in a new window, and overall, diet contributes very little, opens in a new window to variation in urate levels.

So rather than purely focusing on purine-rich foods, consuming less in total, opens in a new window can better control urate levels while improving your overall health. Limiting alcohol, opens in a new window is also a good idea.

With a red bauble stuck on the end of your foot, you learn to appreciate how important your big toe is for mobility.

Eventually, I managed to drop my COVID kilos, opens in a new window, by watching portion sizes, not going back for seconds, replacing unhealthy snacks with fruit, and cutting back on alcohol.

And with that, I’m hoping my first encounter with gout might be my last. Although keeping off the kilos will require constant vigilance, the memory of that painful red bauble should be a powerful motivator.

![]()

Andrew Brown, opens in a new window, Professor, School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, UNSW, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.