Self-assembling nanorobots may sound like science fiction, but new research in DNA nanotechnology has brought them a step closer to reality. Future nanobot use cases won’t just play out on the tiny scale, but include larger applications in the health and medical field, such as wound healing and unclogging of arteries.

Researchers from UNSW, with colleagues in the UK, have published a new design theory in ACS Nano, opens in a new window on how to control the length of self-assembling nanobots in the absence of a mould, or template.

“Traditionally we build structures by manually assembling components into the desired end product. That works quite well and easily if the parts are large, but as you go smaller and smaller, it becomes harder to do this,” says lead author Dr Lawrence Lee of UNSW Medicine’s Single Molecule Science.

Medical researchers are already able to build nano-scale robots that can be programmed to do very small tasks, like position tiny electrical components or deliver drugs to cancer cells.

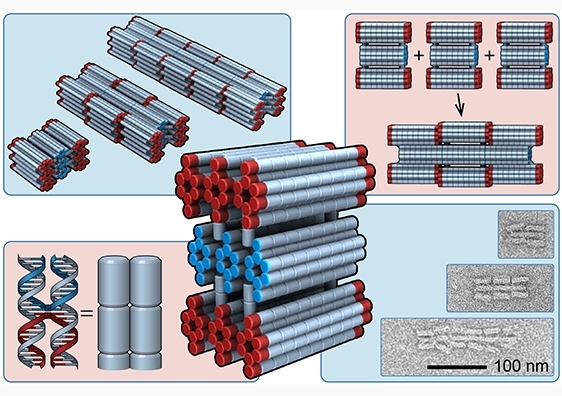

At UNSW, researchers use biological molecules – like DNA – to build these nanorobots. In a process called molecular self-assembly, tiny individual component parts build themselves into larger structures.

The challenge with using self-assembly to build is figuring out how to program the building blocks to build the desired structure, and getting them to stop when the structure is long or tall enough.

For this project, the UNSW researchers implemented their design by synthesising DNA subunits, called PolyBricks. As happens in natural systems, the building blocks are each encoded with the master plans to self-assemble into pre-defined structures of set length.

Dr Lee likens the PolyBricks to the microbots in the sci-fi film Big Hero Six, where microbots self-assemble into a multitude of different formations.

“In the film, the ultimate robot is a bunch of identical subunits that can be instructed to self-assemble into any desired global form,” says Dr Lee.

The authors used a design principle known as strain accumulation to control the dimensions of their built structures.

“With each block we add, strain energy accumulates between the PolyBricks, until ultimately the energy is too great for any more blocks to bind. This is the point at which the subunits will stop assembling,” Dr Lee says.

To control the length of the final structure – i.e., how many PolyBricks are joined together – the research team modified the sequence in their DNA design to regulate how much strain is added with each new block.

“Our theory could help researchers design other ways to use strain accumulation to control the global dimensions of open self-assemblies,” Dr Lee says.

The authors say this mechanism could be used to encode more complex shapes using self-assembly units.

“It’s this type of fundamental research into how we organise matter at the nanoscale that’s going to lead us to the next generation of nanomaterials, nanomedicines, and nanoelectronics,” says PhD graduate and lead author, Dr Jonathan Berengut.