Light, liposomes, action: researchers show safer, more targeted way to deliver CRISPR gene therapy

Biomedical researchers have come up with a novel way to use a beam of light to deliver CRISPR gene therapy molecules targeting illnesses.

Biomedical researchers have come up with a novel way to use a beam of light to deliver CRISPR gene therapy molecules targeting illnesses.

Light-activated liposomes could help to deliver CRISPR gene therapy – and the method could prove safer and more direct than current methods.

A multi-institutional team involving biomedical engineers and scientists from UNSW Sydney found that liposomes – commonly used in pharmacology to encapsulate drugs or genes – can be triggered by light to release the payload in a specific site of the body.

The team, which reported the findings today in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, opens in a new window, demonstrated their results in cell lines and animal models, with more research needed to test and confirm their method in humans.

Up until now, CRISPR gene therapy technology, which uses a guide RNA to seek out faulty gene sequences and a Cas9 protein, opens in a new window to cut or replace it with healthy versions, has used viruses loaded with the CRISPR molecules that then move through the body to find the targeted cells.

While the technology has proved revolutionary – only this year the Nobel Chemistry prize was awarded to researchers, opens in a new window developing the technology – the use of viruses as the delivery vehicle is less than ideal because of the potential for adverse immune response and toxicity.

But in the latest research, the team demonstrated how they could use a much more benign vehicle to carry the CRISPR molecules while using a unique way to deliver them solely to the area of the body in need of them.

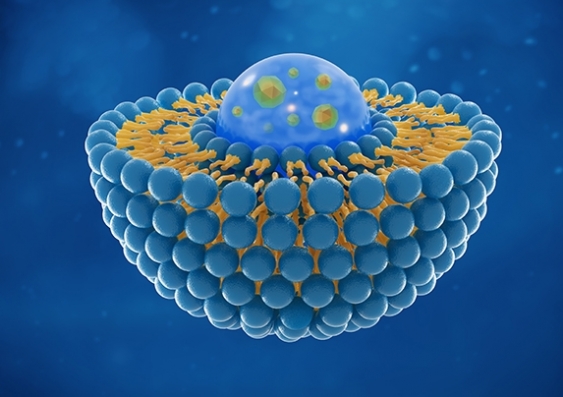

Lead author Dr Wei Deng says the team used liposomes – spherical nanostructures of fat molecules very similar to cell membrane material – to carry the CRISPR molecules to the target site in the body.

“Liposomes are already well established as an extremely effective drug-delivery system,” she says. “These ‘bubbles’ are relatively simple to prepare, can be filled with appropriate medication and then injected into the body.”

Dr Deng says because liposomes are the most common and well-established drug delivery vehicles, they are much safer than using viruses.

“The traditional delivery vehicle of CRISPR is based on viruses, but they create their own problems because it is difficult to predict the reaction of patients to the viruses.”

But having found a safer vehicle to deliver the CRISPR cargo, the team was faced with the challenge of how to ensure these gene-splicing molecules found the right target at the right time. The answer, they discovered, was light.

“Unlike the traditional liposome-based delivery systems, our liposomes can be ‘turned on’ under light illumination,” Dr Deng says. “When light is shone onto the liposomes, they can be disrupted at once, immediately releasing the entire payload.”

The team found in both cell lines and animal models that when the liposomes are triggered by an LED light, they eject the CRISPR contents which go to work looking for genes of interest. Dr Deng says the light can activate the liposomes up to a centimetre below the surface of the skin.

But what if the problem area is deep-seated tumour? Dr Deng says future studies will use X-rays to achieve the same effect.

“We fully expect that we will be able to carry out X-ray triggering of CRISPR delivery in deep tissue at depths greater than one centimetre,” she says.

“Our past research, opens in a new window has already indicated that liposomes can be triggered by X-rays.”

Dr Deng says CRISPR technology is offering exciting possibilities in medical research, especially in treatment of cancer.

“Cancer affects millions of people worldwide, yet researchers have been working for decades to find effective treatments.

“Chemotherapy is great at destroying cancer cells, but because it is untargeted, it ends up damaging normal, healthy cells.

“CRISPR technology has created a very promising tool for developing new targeted, gene and cell-based therapies. Its outcomes would largely increase with the desired delivery system, and in this context, our findings may provide such a system.”

Looking ahead, Dr Deng said she and her colleagues are interested in carrying out research that shows X-rays can be used to deliver CRISPR gene-splicing molecules for deep cancer treatment.

“By using X-ray instead of light we also need to find a proper animal model that might translate to using this technology for something like breast cancer treatment. So we’re looking for collaborators who have this sort of expertise.”