It’s no surprise that NSW is touting changes to the rate and scope of the Goods and Services Tax amid the financial crisis triggered by the coronavirus, says UNSW Business School Professor of Practice Jennie Granger.

The NSW Treasurer, Dominic Perrottet, is promoting the possible changes after a review of federal-state financial relations he initiated last year to reconfigure funding arrangements for the states and protect, he says, NSW’s ability to pay for essential services.

Mr Perrottet is building on the mood for change triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and the significant financial burden it is placing on the state and the nation.

“With state and federal governments building eye-watering deficits, it’s not surprising GST’s 20th birthday was celebrated with intensified calls for reform,” says Prof. Granger.

“When weighing up where you sit on the reform, it’s important to understand what it is and also if you are comfortable with who will be the winners and losers.”

For state and territory governments whose revenues have fallen dramatically since the pandemic took hold, the reform could provide a revenue boost and justify rationalising a range of taxes and duties. But, while a consumption tax such as GST can be relatively easier to collect, it can also be regressive in nature and impact people in lower-income households due to the larger proportion of income spent on consumption goods.

What are our reform options?

“Advocating tax reform that increases tax is not for the faint-hearted and GST reform is particularly controversial. There are two camps on reform: to expand the base or increase the rate – and there is an occasional intrepid soul arguing for both,” Prof. Granger says.

Expanding the base to remove all exemptions would be a return to the original, controversial proposal. Proponents argue that not only is this more efficient, but it modernises GST by recognising that our consumption patterns have fundamentally changed in 20 years. We now consume more services, some of which weren’t around 20 years ago or were too expensive then for most people.

“Most basic foods, some education courses and some medical, healthcare products and services are exempt from GST. These exemptions were an important political line in the sand for getting agreement to introduce the GST 20 years ago and will no doubt be just as hotly defended today,” Prof. Granger says.

The NSW Review of Federal Financial Relations report ordered by Mr Perrottet and chaired by former Telstra CEO David Thodey observed that “further erosion could occur over time if households continue to increase spending on GST exempt services (e.g. healthcare) and if the ageing population results in higher rates of saving”.

The alternative – and considered to be only slightly less contentious – is to raise the GST rate.

Is an increase in GST necessary?

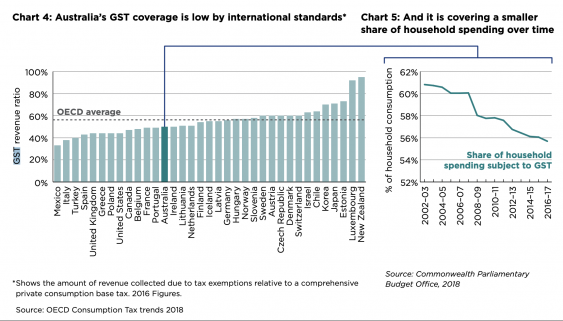

Since its introduction by the Howard government 20 years ago, GST has been a flat 10 per cent tax on domestic purchase of most goods and services in Australia. Mr Perrottet’s report stated that as a result of a high number of exemptions, the GST only covered a small share of all household spending (in comparison to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average), and this was expected to fall over time.

“Under current policy, GST revenues could continue to fall due to a higher health spend (which is exempt from GST) and higher rates of saving from the ageing population. This would leave the states more reliant on funding tied to Commonwealth policy, or their own taxes, to fund the delivery of services and infrastructure,” the report said.

According to PwC's recent report on GST reform, Australia's GST rate ranks fourth-lowest amongst OECD nations.

Hungary has the highest value-added tax at 27 per cent, though comparisons are not straight-forward since countries do not all collect consumption tax at the national level. Canada and the United States both operate on a state-based sales tax, i.e.: each state will impose their own sales tax rate, and in 38 US states, sales tax is combined with a local sales tax.

So, does this mean that Australia has room to increase its GST rate?

GST reform is a sensitive topic politically – as demonstrated by the Prime Minister’s resounding ‘no’ in May 2019 when the Australian Tax Office requested an expansion of the GST base to include packaged goods. However, given the pandemic-induced deficit, GST reform could now be a more palatable discussion for states and territories.

By arguing for an increase in the GST rate, the NSW government is hoping to “offset a decline in the GST base”. But it is a little more complex than that.

“In our winners and losers’ analysis, the reform would be a win for the states. It also could be a win for people and businesses who are paying those state taxes now – if they end up paying less net tax overall,” Prof. Granger says. “Of course, for those of us who don’t have to pay those particular taxes, we are losers because we are paying more tax to subsidise the reform of state taxes.”

Will an increase in GST make up for the deficit?

“It certainly would make a difference to state and territory budgets,” Prof. Granger says. “As a result of the pandemic, we are experiencing the largest fall in consumption in decades. In his December mid-budget update, federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg wrote down GST revenue by $9.9 billion until the 2023 financial year.”

Based on its modelling, PwC Australia also showed that an increase from 10 to 12.5 per cent in GST could generate an extra $14.5 billion. If the base is broadened out to include fresh produce such as fruits and vegetables, childcare and education, revenue could be further increased to $40 billion. And if the GST base is broadened but tax rate remains at 10 per cent, an extra $20.7 billion could be generated.

However, PwC Australia also noted the disproportionate effect this could have on low-income households and advised the government to have a deep understanding of the implications before implementing the reform.

GST holiday in favour of an increase in GST rate?

Some researchers have also been advocating for a GST holiday instead of increasing the GST rate. This is based on the fact that GST is typically imposed on non-essential items such as local travel, eating out and shopping. So, increasing the GST rate could defeat the purpose of the reform and further alienate people from spending.

However, by applying a GST holiday on consumption goods, people could have an incentive to spend more on non-essential items – spending habits that are very much needed to stimulate the economy again.

“A temporary exemption could be helpful as lowering the cost of spending could ease some pain on cash-strapped households and could encourage more spending on non-essential consumption. This could be a boost for struggling service sectors such as restaurants, entertainment and domestic tourism,” Prof. Granger says.

How likely is the GST reform?

Would the federal government agree to a holiday for which it would bear the cost?

Prof. Granger says that achieving consensus on such a contentious reform is extremely difficult.

“The federal government has made clear it would need consensus amongst the states and territories to have it seriously on the agenda. Even with the heightened level of cooperation in the National Cabinet, it’s hard to see the reform being a priority. And then, of course, there’s the Senate.

“For many Australians hit hard by the pandemic, it’s difficult to see why we would want the cost of our spending to rise at this time. We would have to be persuaded on how we could be winners, too,” Prof. Granger says.