COVID-19 provides a stark reminder of inequity and the spread of disease. These aren’t new ideas and can be traced back to John Snow’s cholera maps and Charles Booth and his colour-coded maps of occupation types and poverty in the 19th century. Today, as case numbers soar in Melbourne, large clusters of COVID-19 cases have been identified across the northern and western suburbs, raising questions about occupation types and socio-economic differences across the city.

One of the most important messages from government during the pandemic has been to work from home if you can. Though what happens if your work isn’t suited to this?

Snow and Booth were forefathers of modern geographical information systems (GIS) analysis. It’s a powerful tool for mapping and visualising differences or inequities across cities and the spread of disease. We mapped the connection between occupation types, indicating the ability to work from home, and the locations of COVID-19 cases across Melbourne in the recent second wave.

Why is equity a health issue?

Hotspot suburbs were first identified and ring-fenced in early July. A hard lockdown was applied to the 3,000 residents of nine high-density public housing estates in inner Melbourne.

Ring fencing is a powerful method of containing a disease. It’s most appropriate where a specific location has a distinctive pattern of risk. It should also be applied without bias.

As the public housing towers lockdown reminded us, there is an inequity in health.

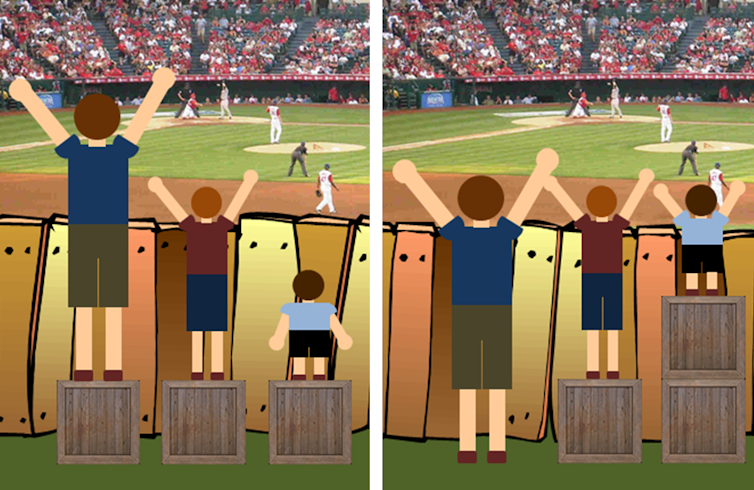

Many people associate equality with treating everyone the same regardless of their needs. This is very different to equity, which is about treating people according to their needs. Unlike equality, equity is providing people with extra help when it is needed.

The picture below makes the concept of equity easier to understand.

Craig Froehle/Medium, CC BY

In the context of this pandemic, a recent discussion of housing affordability raised the issue of equality versus equity.

We see a stark difference between the initial transmission of COVID-19 and the second wave. The earliest cases were concentrated in Melbourne’s wealthier areas and associated with international travel. In the second wave we have seen a different pattern of spread across disadvantaged areas of Melbourne.

This pattern is possibly linked to inequity associated with living and work conditions. People with higher education tend to work in occupations that often enable them to work from home, making it easier to self-isolate.

Outer areas of Melbourne have had more cases of COVID-19 cases in the second wave and this might be associated with job types and education levels. Residents living in inner areas of Melbourne are more likely to hold tertiary qualifications needed for occupations more suited to working from home.

What does mapping reveal?

We analysed Australian Bureau of Statistics Census data on employment types from the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations. We identified 93 major occupation types suitable for working from home.

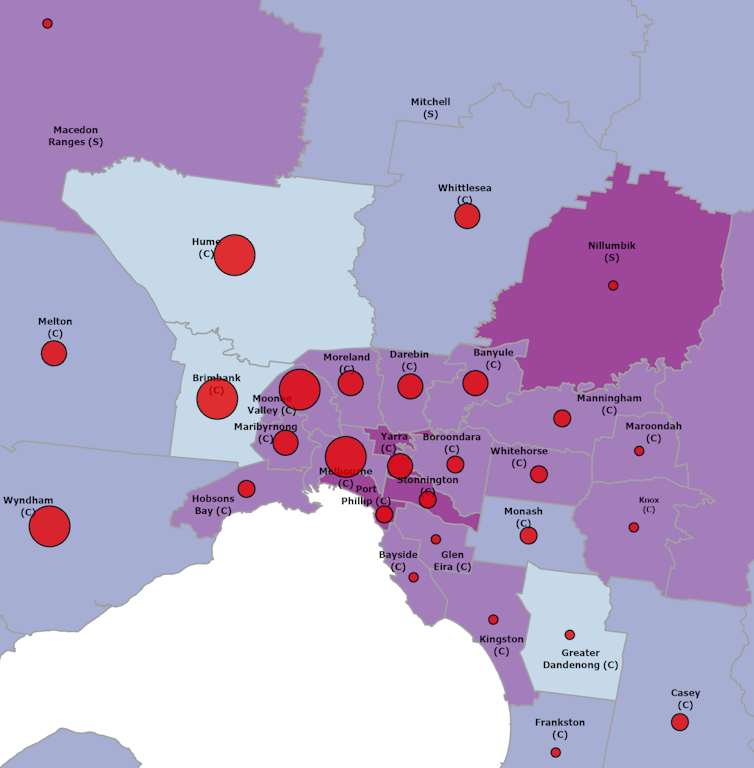

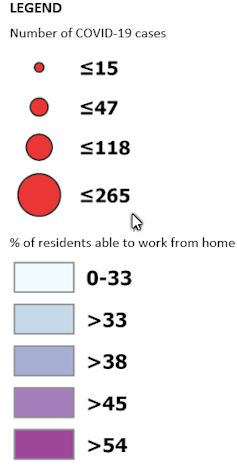

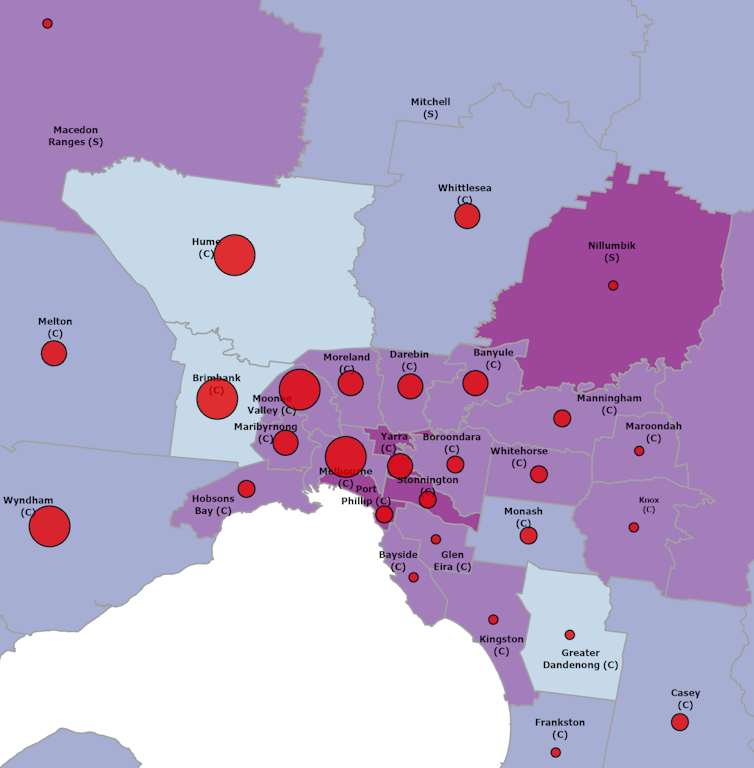

We linked and mapped these occupation data along with COVID-19 incidence according to local government areas. The map below shows data from July 16.

Data: DHHS, July 16, Author provided

The map reveals lower proportions (shown by lighter-coloured areas) of people employed in occupations suitable for working from home in many outer northern and western areas of Melbourne. In particular, the proportion is low in Hume, one of the local government areas where COVID-19 cases have been concentrated.

In the inner and outer eastern areas of Melbourne, residents are more likely to be able to work from home. Nillumbik in the outer north-east has the highest proportion of people able to work remotely. It has very few cases of COVID-19.

Greater Dandenong is an exception to this pattern. As a manufacturing hub for Melbourne, it has a low proportion of people in occupations suitable from working from home, but has few cases.

COVID-19 is spread through community transmission or close contact with others who are infected, as happened in meatworks factory clusters in northern and western Melbourne. Greater Dandenong may have been protected by the small number of cases across south-eastern Melbourne where more residents have occupations suitable for working from home.

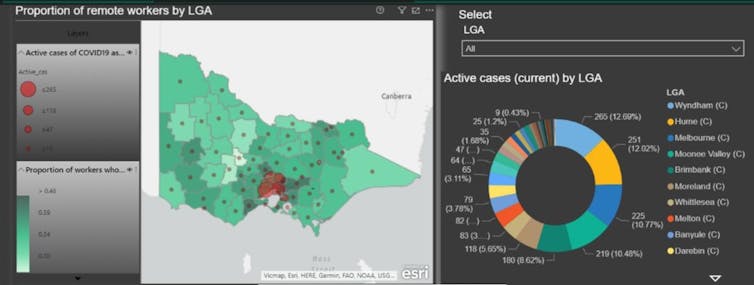

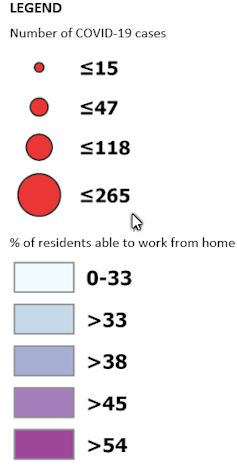

The Victorian Department of Health and Human Services updates COVID-19 incidence data hourly. We first sourced data on July 16, a week after the Melbourne-wide lockdown began, to understand the patterns of occupation types and COVID-19 clusters as they evolved. To continue monitoring, we have developed a data dashboard, which is shown below.

Ori Gudes, Author provided

We hope this data dashboard will be released in coming days with updated data.

Using inclusive data to protect everyone

The related patterns of occupations and COVID-19 incidence remind us of the importance of the well-known relationships between health and place.

This pandemic takes advantage of inequity and our most vulnerable communities. It shows us why we must include the full spectrum of society (not only those we know best) when we make decisions, communicate and ask people to work from home.

Many workers are engaged in casual and insecure employment and work is a critical determinant of health. Our mapping provides evidence that can help authorities decide where and how to focus preventive measures when planning public health interventions.

These methods of GIS analysis and easily understood maps should be freely available. The community will then be able to interrogate the data so they can realise in close to real time the rationale for public health directives.

These same principles have been used to understand health and liveability in cities though the Australian Urban Observatory to inform city planning.

We thank Weijia Liu of UNSW for assisting with data collection in this study.

Melanie Davern, Senior Research Fellow, Director Australian Urban Observatory, Co-Director Healthy Liveable Cities Group, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Mary-Louise McLaws, Professor of Epidemiology Healthcare Infection and Infectious Diseases Control, UNSW, and Ori Gudes, Senior Research Fellow, Geospatial Health Lab, University of Canberra, and Adjunct Senior Lecturer, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.