In an open letter to Attorney-General Christian Porter, about 500 women working in the law from across Australia have sought changes to the way judges are disciplined and appointed.

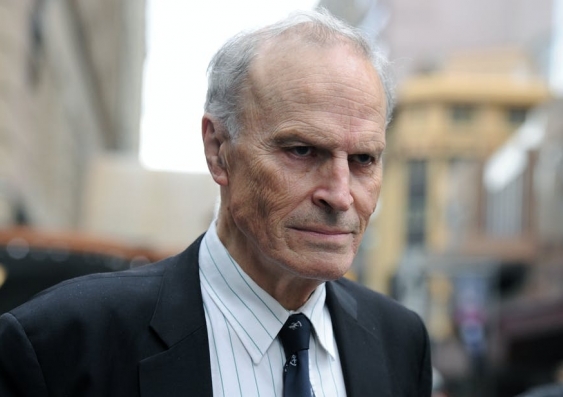

The letter comes after former High Court judge Dyson Heydon was found by an independent investigation to have sexually harassed young female associates of the court, as reported by The Sydney Morning Herald.

The letter was also sent to Susan Kiefel, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, along with another letter to thank her

for her strong, decisive and compassionate responses to the complaints in the Heydon matter, and ask her to work with the government to see these reforms implemented in a way sensitive to the protection of judicial integrity and independence.

The full text of the two letters are below.

Dear Attorney-General

We are writing following the publication of the High Court’s response to the complaints about the conduct of Mr Dyson Heydon AC QC during his time as a judge on the Court. As women working across the legal profession, we have welcomed the Chief Justice’s strong response to the independent inquiry’s recommendations about providing better protections to associates during their time employed at the Court, recognising their particularly vulnerable professional position.

We believe the abuse the allegations raise provides an important opportunity to implement wider reforms to address the high incidence of sexual harassment, assault and misconduct in the legal profession. Deep cultural shifts in how men treat women in the law are required, as well as reforms to prevent the manifestations of what many fear may be institutionalised sexism that has allowed this culture to continue. We must reach a position where all people, regardless of their sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, age, race, ethnicity, or disability are treated with equal professional dignity. Of course, no single reform can achieve these shifts, and we understand many different forms of change must be pursued.

We are writing to urge you to implement two types of judicial institution reform – the establishment of an independent complaints body and the introduction of a transparent appointments process. We believe these will prove to be important systemic contributions towards deeper cultural shifts.

To ensure these reforms are introduced and designed with appropriate levels of respect for the independence of the judiciary, we ask you to develop them with the cooperation and input of the judges. We encourage you to work with the Chief Justice of the High Court, to whom we have provided a copy of this letter, and the Council of Chief Justices of Australia and New Zealand to see them implemented. The Council of Chief Justices also offers an opportunity for these reforms to be considered at a national level to operate not just for the federal judiciary, but potentially across the federation.

First, we encourage the creation of an independent complaints body, with a standing jurisdiction to receive complaints against federal judges, investigate any complaints and provide appropriate responses to them. This institutional reform would ensure there is an established body to which future complainants may turn, whether they be court employees, members of the profession, the judiciary or members of the public. It would provide an independent avenue for individuals to seek redress with some guarantees of privacy and protection against recrimination, such as defamation actions.

An oversight institution such as this must be carefully designed so as to meet expectations of accountability for judicial misconduct, while protecting judges from unfounded allegations and not placing the judiciary in a subordinate position to any other branch of government. We underscore the necessity of any institution to respect judicial independence, and the requirements of Chapter III of the Constitution. If well designed with these considerations in mind, we believe such an institution could enhance public confidence in the integrity and independence of the judiciary.

In respect of its design, any institution should be informed by best practice and the standards that apply to complaint handling, such as ISO 10002:2004: Quality Management – Customer Satisfaction – Guidelines for Complaint Handling in Organizations. It should also be informed, although not limited, by the design of institutions that are already operating in many jurisdictions, including the Judicial Commission of New South Wales, the Judicial Conduct Commissioner of South Australia, the Judicial Commission Victoria, the ACT Judicial Council and most recently, the Judicial Commission of the Northern Territory.

Informed by such standards and the experience of these jurisdictions, we propose the following principles for the design of a national judicial complaints institution:

-

there must be clear, publicly available standards against which appropriate judicial behaviour is assessed. These standards must be developed by the judiciary to ensure independence from the political branches. The Guide to Judicial Conduct, adopted by the Council of Chief Justices, provides an important starting point as to the types of conduct that are unacceptable in judicial office. However, these standards need to go beyond aspirational statements and set down enforceable standards of appropriate conduct, including examples of behaviour and the consequences that might follow from such behaviour. Further, these standards should specify that workplace harassment and bullying, including sexual harassment, constitute judicial misconduct; conduct which is currently not mentioned in the Guide

-

the body should be a standing body, separate and independent from the political branches of government. It should be appointed by the judiciary, to maintain judicial independence, but it must be separate from the ordinary judicial hierarchy and process

-

the body may include former judicial officers, and there should be diversity in its membership

-

the body must adopt a robust, fair and transparent process. It must have appropriate investigative powers and ensure procedural fairness is accorded to complainants and the respondent. It must also protect the privacy of complainants and provide them with guarantees against recrimination, including defamation proceedings

-

should the body determine that a complaint has been made out, it must have an appropriate suite of avenues for redress available to it. These might include: referral to Parliament for possible removal; referral to prosecutors in relation to possible criminal conduct; as well as intermediate forms of redress, such as public reprimand, orders for compensation, and recommendations for pastoral care and advice (eg mentoring). While there are concerns that such responses might undermine public confidence in the judiciary, we believe the revelation of misconduct without a mechanism for appropriate redress also poses a high risk of such damage.

-

the body must have jurisdiction that extends to the investigation of retired judges and chief justices. Its jurisdiction must include conduct on the bench, notwithstanding that a judge has subsequently resigned. Second, we urge systemic reforms to the process of judicial appointments to increase transparency and promote the independence, quality and diversity of the judiciary. These reforms must be targeted to select candidates that will bring not just excellent legal skills to the office, but also the highest personal integrity, and contribute to greater diversity in the senior ranks of the profession.

In respect of its design, we proposed the following principles:

-

the government should appoint an independent body, composed of a diverse range of members, appointed by the judiciary and the government through a transparent process, to advise the government in its role in judicial appointments

-

the body’s function should be to advertise widely for judicial vacancies, and to shortlist candidates who are suitable for appointment, from whom among the government may select.

-

shortlisting must occur against criteria that are set out in a public statement, and must include legal knowledge, skill and expertise in addition to essential personal qualities (eg integrity and good character). The value of diversity in judicial appointments should also be respected. The Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration’s Suggested Criteria for Judicial Appointments provides an example of such a statement

-

the body must consult widely, with relevant professional bodies and officeholders, including those representing women and other minority stakeholders, before shortlisting candidates

-

The body’s processes must be transparent.

We hope government will seize the opportunity these shocking revelations have provided to implement these, and other, reforms that will contribute to making the law a safer profession for women into the future.

Yours faithfully,

See all signatories here.

Dear Chief Justice,

We are writing following the publication of the High Court’s response to the complaints about the conduct of Mr Dyson Heydon AC QC during his time as a judge on the Court. We thank you and the Court’s Principal Registrar, Ms Philippa Lynch, in particular for the decisive action taken to ensure the complaints were thoroughly investigated by an independent process. We are grateful that you took this matter so seriously and treated the complainants with dignity, compassion and respect. We welcome your response to the inquiry’s recommendations as to how to provide better protections to associates during their time employed at the Court, recognising their particularly vulnerable professional position.

Today, we have sent a letter to the Commonwealth Attorney-General urging him to seize this moment as an opportunity to implement reforms to address the high incidence of sexual harassment, assault and misconduct in the law. We have asked that he take action to implement two types of institutional reforms – an independent complaints body and a transparent judicial appointments process. While no single reform will achieve the necessary cultural shifts in how women are treated in the law, we believe, if properly designed, these will prove to be important systemic contributions towards deeper change.

We are very conscious that these reforms must be developed through close cooperation between the government, through the Attorney-General’s portfolio, and the judiciary. In particular, the creation of an independent complaint-handling body with a standing jurisdiction to receive complaints against federal judges, investigate any complaints and provide appropriate responses to them, must be designed with care. It must meet expectations of accountability for judicial misconduct while protecting judges from unfounded allegations and not compromising judicial independence by placing the judiciary in a subordinate position to any other branch of government.

With these considerations in mind, we have asked the Attorney-General to work with you and the Council of Chief Justices of Australia and New Zealand as an important forum for input from the Australian judiciary into the design of these reforms. We applaud your initial response to this issue. The changes you and Ms Lynch have made will form a significant legacy and will make the law a safer profession for women.

See all signatories here.

Gabrielle Appleby, Professor, UNSW Law School, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.