Social robots show promise for future pandemics

The early adoption of social robots, in the healthcare and service industries, illustrates their potential to assist in future crises.

The early adoption of social robots, in the healthcare and service industries, illustrates their potential to assist in future crises.

The full economic fallout from the recent shutdown of businesses and the introduction of social distancing to stem the spread of COVID-19 cannot yet be known. But the fact that we were not prepared to deal with this kind of global crisis, and that we will sustain significant future consequences as a result, is indisputable.

Technology will play a significant role in these changes.

The COVID-19 crisis offers us the opportunity to explore alternative technologies that could provide advantages over conventional screen technologies, such as new coping techniques and ways to minimise risks for frontline workers in this crisis.

These technologies include social and service robots.

Robots can assist with boring, meaningless and dangerous activities, but they can also bring happiness, satisfaction, peace, entertainment and comfort (including emotional comfort). These robots are called social robots.

A social robot is a computer that has the capability to interact with the physical world and its users in a social manner. These robots have bodies – they are often human-like or animal-like in form. Similarly, social robotics is the study, analysis and design of a broad range of human-robot interactions.

As a relatively new multidisciplinary research field, most existing social robots and studies of human-robot interactions remain in the research space. However, due to the rapid improvement of technologies integrated into social robots, researchers have begun investigating human-robot interactions “in the wild” (in non-controlled or semi-controlled conditions) with positive outcomes.

For instance, Paro, a Japanese companion robot shaped like a baby harp seal, has been used in healthcare and rest homes, predominantly for companionship and therapy in dementia care. Paro moves and makes seal noises in response to light, touch, sounds and orientation. Thousands are in use across Europe, the United States and Asia, with randomised trials suggesting that the robot reduced loneliness and increased social interaction.

As well as positive responses however, there has also been research exploring negative interactions between children and social robots in public spaces, as well as longitudinal studies showing a lack of engagement with social robots in domestic homes.

These studies show there is a long way to go before social robots become valuable commercial technologies. There are common failures in the development of social robots for use outside the laboratory, such as engineering needs supplanting design and the challenge of overcoming negative preconceptions.

But, while we need to invest in research to refine social robotic technologies, they may prove vital to help us cope with the changes that COVID-19 will have on our lives, perhaps permanently. Following are some future scenarios that can be envisioned for social robots.

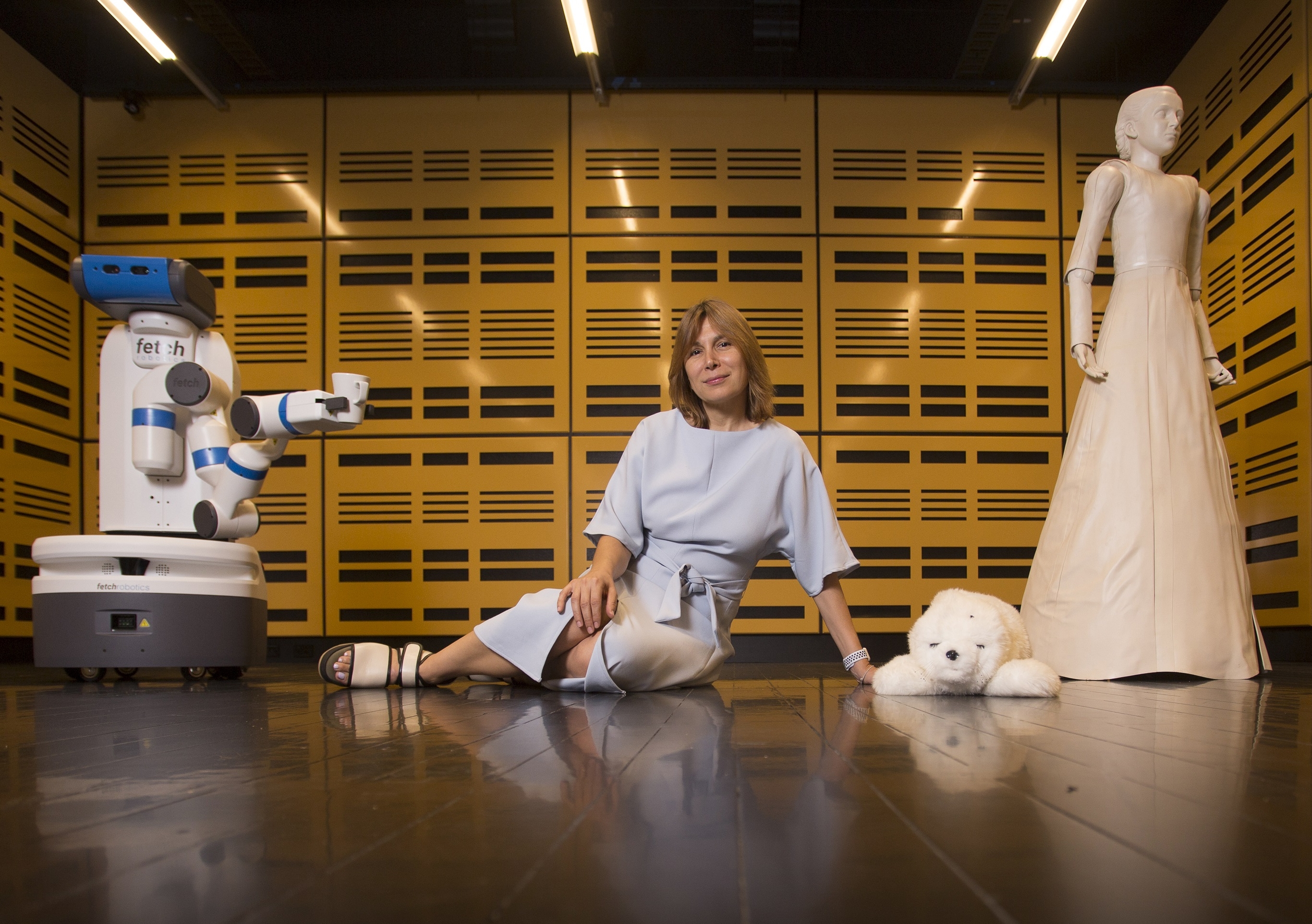

Professor Mari Velonaki and friends in the Creative Robotics Lab. Photo: Quentin Jones

Humans are social animals. A lot of our achievements as species are the product of our social interaction. While there is a constellation of apps to motivate us, to create new habits and track them, social robots have the potential to further engage users.

While there are chatbots and avatars for therapy and coaching, just a few social robotics projects have explored their use as a therapeutic tool for specific populations. However using social robots for therapy has been discussed since the early stages of human-robot interaction with various different frameworks proposed.

At the UNSW Creative Robotics Lab, Dr Scott Brown has used a social robot Kaspar to develop a framework to help autistic children recognise the emotions behind different facial expressions, using a co-design approach to provide guidelines for future design. We have also carried out pioneering work in the use of robots to facilitate conversational interventions with dementia patients.

The provision of care by social robots in healthcare settings has grown significantly in the last decade. And just a few weeks ago, a new social robot named Moxie that generates play-based learning for kids was released.

Social robots could indeed be used by the general public once the technology is further developed.

Dr Scott Brown has used a social robot Kaspar to develop a framework to help autistic children recognise the emotions behind different facial expressions. Photo: UNSW

Social robots have the potential to provide an alternative to human-to-human entertainment – engaging with board games, card games, roleplay or video games, for example, both as autonomous robots or as interfaces to play remotely with friends.

Ping-pong has long attracted the attention of robot developers and researchers. For example, the robot Forpheus from Omron trains table-tennis players using an industrial robotic arm. Cost remains a barrier here for wide take-up (there being cheaper, less sophisticated alternatives for training). Furthermore, the technology needs to be developed to make the robot compete against the player, and an interactive social interface would also be a plus to engage with the users.

At the UNSW Creative Robotics Lab, we are developing prototypes using robot arms and humanoid robots to play memory games. While still in the early stages, they promise new ways for social interaction in indoor environments that could help develop this cognitive skill.

Similarly in the exercise arena, with the increasing popularity of online yoga, resistance training, and rehabilitation tutorials, social robots could provide a valuable tool to deliver training activities in a superior way to existing technologies. They could support the work of trainers and assist in the feedback and supervision in real time.

CSIRO and UNSW researcher Dr David Silvera have explored the use of miniature humanoid robots to help children with autism learn yoga at Murray Bridge High School in Adelaide, but further work is required to make these robots broadly usable.

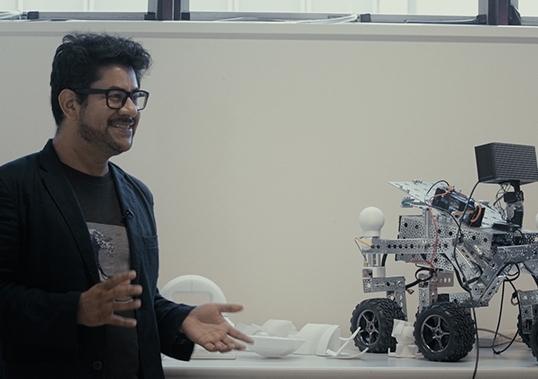

Dr Eduardo Benitez Sandoval. Photo: Eduardo Benitez Sandoval

The COVID-19 crisis presents areas of opportunity for the development of new technologies to assist in this emergency for frontline health workers. For instance, robots capable of interacting with highly infectious patients would help keep doctors and nurses safe.

These robots would require excellent dexterity to manipulate complex objects within their environments. Artificial intelligence used in conventional ways is not enough. As my colleague, Dr. Binghao Li, says: “Artificial Intelligence is not intelligent if it doesn't interact with the environment”.

Furthermore, these robots would need a social interface capable of interacting with healthcare personnel and patients to assist with the patient's recovery and collection of prognosis information.

A recent example of robots used in hospitals during the pandemic is the Spot robot dogs with an iPad built into their bodies. These robots provide remote consultation and are controlled by a doctor remotely, keeping a safe distance between potentially infected patients and healthcare staff.

Robots are also used in hospitals and hotels in countries like China and the US to deliver medication to patients in isolated rooms. However, these robots require significant human assistance. Moxi by Diligent Robots offers another approach, providing assistance with routine non-patient-facing tasks in hospitals.

Robots are also in use in retail stores and malls in Korea, China and Japan helping customers find particular products, or guiding them to specific stores as an information service. These robots have humanoid bodies and specific social skills but are operated using a touch screen. They can foster social distancing and mediate the interaction between customers and retailers.

Despite their limitations, the increasing number of robots in the retail industry could help the retail industry compete with the robust online retail market.

Robots are also moving into the food and beverage market. There is an ice cream shop in Melbourne using robot arms and humanoid robots to deliver an exciting experience to the customers. A cruise company and bars around the world are trialling robot arms to prepare drinks for the patrons.

Here the robots add an entertainment element to the experience. They also increase potential hygiene by avoiding human manipulation. Adding a social component to these robots could add a lot to the human-robot experience in the future.

While I believe these technologies would best serve the fast-food industry, we may reach a stage where to have a meal prepared by a human is a luxury.

State-of-the-art sensors capture a human/robot interaction at the National Facility for Human Robot Interaction Research to assist in social robotics research. Photo: Andrew Haigh

Some people are afraid robots will take human jobs, but robots can pave the way for humans to instead have meaningful jobs with purpose.

My position is that robots are tools. They should enhance our capabilities as humans in the same way that pencils, hammers, bicycles, and computers have helped us to be faster, more reliable, relevant, and useful for others. Service and social robots could be used mainly for activities humans don't want to do and also add an important social component in other activities to provides us comfort, happiness and safety.

Australian researchers have in front of them a tremendous opportunity to invest in these robot technologies after the changes we will see following this health emergency. Indeed, this emergency will not be our last, and we need to prepare now for the next. Robots, particularly social robots, can keep us safe, comfortable and ensure we are emotionally ready.