The COVID-19 pandemic is a double crisis affecting public health and the economy. And both aspects are playing out in our housing system – in our homes.

More and more of us are being directed to stay home, to work from home, or to socially isolate at home. Our homes are the “first line of defence against the COVID-19 outbreak”, as the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Housing puts it. But, depending on how our housing system responds, it could make the double crisis worse.

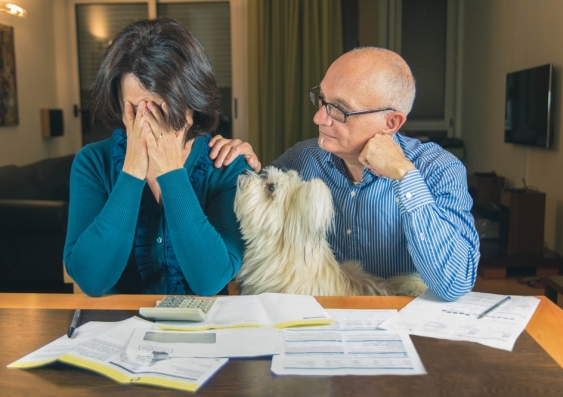

More and more workers are losing shifts, or losing jobs altogether, as well as the incomes they use to pay for their homes – whether it’s the rent or the mortgage. On Friday, the prime minister announced that states would work on model rules to provide relief to tenants in “hardship conditions”. On Sunday, the federal government moved to replace some of the income households have lost, temporarily doubling some social security payments and making cash grants to businesses.

The risk of people becoming homeless during the pandemic is still high. Some more specific actions are needed to shore up our first line of defence. Governments must implement a moratorium on evictions as long as the crisis lasts. Similar changes have already been made overseas.

Evictions can happen quickly

A sudden loss of wages puts renters at risk of arrears and owner-occupiers at risk of mortgage default. This may result in legal proceedings to terminate the tenancy or give possession to the bank or other lender, and ultimately eviction. Tenants are vulnerable to termination and eviction for a host of other reasons, too.

Renters are at particular risk because rent arrears termination proceedings are quick. You can go from a missed payment to termination orders in about eight weeks in New South Wales. Other states and territories are similar.

Many renters’ finances are already precarious. About one-third of private renters are low-income households in housing stress (in the bottom 40% of household incomes paying more than 30% of income in rent). And 30% don’t have $500 saved for an emergency.

Homeowners with a mortgage are also at risk of default due to loss of income. About 20% of mortgagees are already in mortgage stress. This rate has grown over the last year despite rate cuts.

Now workers are facing sudden income and job losses. We see widespread evidence of an economic downturn across many sectors, including tourism, hospitality and the arts. Casual workers are at particular risk of reduced income if required to self-isolate for long periods or care for unwell family members.

A breach of our defences

An eviction is a breach in the first line of defence that housing provides against COVID-19. In fact, the risk of arrears and eviction might drive an infected person to keep working and transmitting the virus.

An evicted household might pile in with family or friends, disrupting social isolation and contributing to unsanitary overcrowding. It’s a challenge people already living in share housing will have to manage. Across Australia, 81,000 dwellings are already overcrowded, 51,000 of these “severely overcrowded”.

People who have been evicted might move through temporary accommodation, and through real estate offices, social services and doctors’ rooms making urgent applications. Or they may be shut out of assistance, and sleeping rough. With limited space and facilities to wash hands and personal effects, the risk of transmission will grow.

How would a moratorium work?

These risks justify a government-imposed moratorium on evictions for the duration of the crisis. This could be done through legislation, or through an emergency executive direction to authorised officers to stop evictions. Other countries have already taken such steps.

In the United States, many states and cities have suspended eviction proceedings against tenants. Federal housing finance agencies have implemented a 60-day moratorium to protect some families from mortgage default.

Ireland has also suspended evictions and temporarily frozen rent increases. In the United Kingdom, renters in the private or social sector are to be protected from eviction.

A moratorium on evictions is an obvious triage measure. That’s why in Australia a community coalition has come together to advocate for no evictions during this crisis. You can show your support by signing the petition.

The federal opposition is urging the government and financial institutions to consider similar measures.

What about the mounting debts?

By itself, an eviction moratorium doesn’t affect the legal liability to pay rent or mortgage instalments. Without anything more, those liabilities would continue.

The federal government’s increased social security payments and business grants will go some way to replacing the income households are losing. But even as the government tips money into households, money is drained away by rents and mortgage payments.

About A$40 billion is due to flow out of Australia’s 2.5 million private renter households and into 1.3 million landlord households. Landlord households have, on average, much higher incomes and wealth than other households.

Billions more are due to flow, as principal and interest payments, from 3.4 million owner-occupier mortgagees to the banks. Australia’s big four banks last week announced borrowers could “pause” their payments as a pandemic hardship measure. But mortgagees should be aware interest not paid is capitalised into the debt, so they will have more to pay off after the “pause” ends.

Both to prevent the accumulation of arrears, and to make the government’s income-replacement measures more effective, governments should consider implementing reductions or waivers of rent and interest liabilities for as long as the crisis lasts.

The double crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic needs a dual response that aims to keep households in their homes and to keep income in households.

Sophia Maalsen, ARC DECRA Fellow and Lecturer in Urbanism, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney; Chris Martin, Senior Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW; Dallas Rogers, Program Director, Master of Urbanism, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney, and Emma Power, Senior Research Fellow, Geography and Urban Studies, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.