Following the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, the Indonesian government initiated a policy to mainstream disability into development programs. All government departments, at the national and local level, now have guidelines that require the participation of disabled people in all processes of planning a development and its execution, through to evaluation and monitoring.

However, Antoni Tsaputra’s research findings show that, at this stage, the implementation of the policy isn’t progressing well.

“There are many factors influencing this,” he says. “Disability is yet to become a priority in development, and people with disabilities still face a lot of barriers and challenges that will need to be overcome before they can participate actively.”

Mr Tsaputra says that, interestingly, all the disability case studies in his thesis show that people with disability really want to be active agents in development and they are very aware of their rights as citizens.

“One of the biggest contributions my thesis makes is to draw attention to the rights and citizenship of people with a disability. In Indonesia, participating and contributing to development is both a right and an obligation. It’s the same thing. Disabled people are really aware of their citizenship rights.”

‘Difabel’ citizenship – contributing to nation building

Mr Tsaptura says that in Indonesia the citizenship rights of disabled people are referred to as ‘difabel’ citizenship.

“’Difabel’ is a term introduced by Indonesian disability activists to counter the labels previously given to people with a disability,” he says. “Before, in Indonesia, we called them ‘people with defects’ – people who need to be helped and who have become a burden. Using ‘difabel’ shows that disabled people are making contributions to society, to the state and to the nation.

“We call this ‘nation building’, which is a very important concept in Indonesia. Disabled people want to be part of that.”

One of Mr Tsaputra’s case studies focuses on a local disabled people’s organisation which participated in the development policy planning as well as some of the construction, together with the government and other bodies. As a result, all offices and public facilities were built with the required accessibility.

Another case study looks at an economic environment program where disabled people were able to influence their village development policy to meet their needs. For example, when they want to start a business, they are accommodated in village-level budgeting and planning.

“I do really hope that some key findings in my research will become a reference for the government, because my research shows what the policy lacks and how it can be better implemented in the future,” Mr Tsaputra says.

“It’s possible the government wasn’t sure whether disabled people could really participate at all levels of development, but these village organisations have real knowledge of disability.”

The journey to disability advocate and researcher

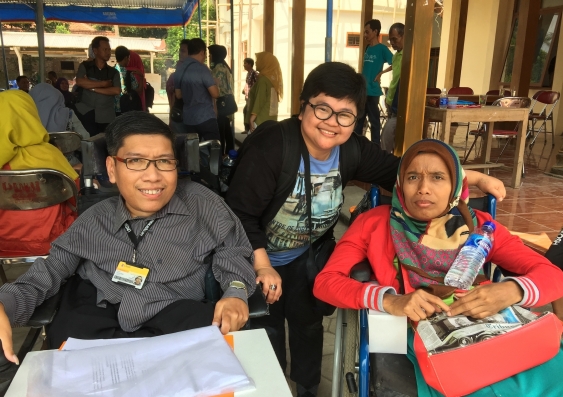

Mr Tsaputra, himself, has lived experience of disability. Having been diagnosed with a form of muscular dystrophy at a young age, he uses a wheelchair to move around. He says he would not have been able to complete his PhD thesis without the support of UNSW’s School of Social Sciences, and particularly his supervisor Professor Leanne Dowse.

After growing up in Bukittinggi, West Sumatra, he completed his undergraduate degree in English literature at Andalas University in Padang. He was awarded an AusAID scholarship and studied for a Masters in Journalism and Communications in Australia. Back in Indonesia, Mr Tsaputra became actively involved in Indonesian disability movements and worked at the Social Affairs Agency of the Padang municipal administration, where he designed programs for empowerment of persons with disabilities. He also ran the city's local chapter of the Indonesian Disabled People Association.

“I am in a unique position because at the same time I am a researcher, a government bureaucrat and a disability activist. Now I have to focus – I will still be a disability activist, but I also want to be a disability researcher,” Mr Tsaputra says.

“When I started my PhD, I had already made a plan that my research would start here. And doing this PhD has really convinced me that research is my first choice. I will keep working on disability policy issues, because my research interests are around disability inclusion and development, disability and inequality, and disability rights realisation, especially in the countries of the Global South.”