The essential Duchamp: an exotic radical who rejected the establishment

Some 50 years after the death of Marcel Duchamp, a major exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW shows why his work continues to challenge the very idea of what art may be.

Some 50 years after the death of Marcel Duchamp, a major exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW shows why his work continues to challenge the very idea of what art may be.

In 1912, a young Cubist painter, Marcel Duchamp, entered his painting, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. This was the preferred venue for exhibiting radical art, as it never rejected anything submitted for display.

Nude Descending a Staircase is a masterly study in tonality and geometry, its edgy movements layering into multiple versions of the androgynous form in rapid motion.

Read more: Explainer: cubism

The dogmatic Cubists saw nudes as being horizontal and passive, not vertical and mobile. They were disconcerted by the way Duchamp had painted a circular pattern of dots to indicate rhythmic movement and saw the large printed title at the bottom of the front of the painting as vulgar.

Having negotiated the previous year to run their own hanging committee, they demanded that Duchamp change the painting. He refused and withdrew it from the exhibition.

Although Nude Descending a Staircase was subsequently exhibited elsewhere, the scandal of this historic rejection marked him as an artist who would clash with established beliefs, whatever the situation.

This and many other works are currently on view at the Art Gallery of NSW in The essential Duchamp, a comprehensive survey of the artist who, more than any other, changed the direction of art in the 20th century – and beyond.

With the exception of his paintings they are not the first originals, nor are they unique. They are however from the largest single collection of Duchamp’s work in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, much of which was donated by his longstanding patrons Louise and Walter Arensberg.

There is nothing unusual about artists stretching the barriers of received wisdom and moving across different styles. However Duchamp did more than this – he rejected the profession of artist. He subsequently trained as a librarian and worked in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, which fed his passion for archives.

As Duchamp explained in a 1956 interview with the curator James Johnson Sweeney: “There are two kinds of artists: the artist that deals with society, is integrated into society, and the other artist, the completely freelance artist, who has no obligations.” Duchamp relished his lack of obligation.

In 1913, on a whim and for the pleasure of seeing the moving spokes, he screwed a large bicycle wheel onto a kitchen stool. At about the same time he also bought a metal rack for drying bottles.

Two years later, having relocated from wartime Paris to New York “to escape from leading the artistic life”, he asked his sister, Suzanne Duchamp, to send these items as, “I have bought various objects in the same taste and I treat them as ‘ready-mades’.”

Suzanne had already cleared his Paris studio of such detritus, but as the concept of ready-made denied the existence of an “original”, this was no problem. Her brother saw these works as “a consequence from the dehumanisation of the work of art”.

Read more: Here’s looking at: Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel 1913

Presenting mass produced works as art seemed a logical act to undertake in the USA, which had pioneered mass production. Duchamp’s status as an exotic radical meant that his first ready-mades, exhibited in New York in 1916, did not cause a sensation.

In April 1917 a new group, The Society of Independent Artists, held its first exhibition in New York. Walter Arensberg was the fledgling society’s managing director and Duchamp became chairman of the hanging committee. In the spirit of openness it was agreed that any artist who paid the membership fee could exhibit two works, to be hung alphabetically.

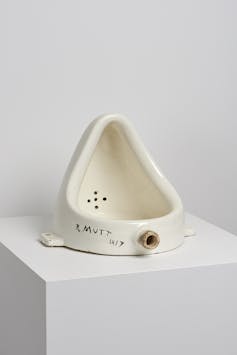

Duchamp arranged to have a ready-made, Fountain, submitted by “R. Mutt”. The name was a play on the J. L. Mott Iron Works where Duchamp had purchased the urinal.

The committee rejected Fountain, claiming it was not art. Duchamp and Arensberg resigned in protest. They took Fountain to Alfred Steiglitz, whose photograph of the work was then reproduced on the cover of the avant-garde magazine The Blind Man.

Beatrice Wood, a friend of Duchamp, wrote that the maker of Fountain was irrelevant: “[Duchamp] CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a thought for that object.” Fountain became the most notorious ready-made in the history of art.

The artist did not differentiate between completed work and the ideas, notes and associated ephemera, so these too are on display in the exhibition. The many mechanical reproductions of Nude Descending a Staircase, always in a slightly different context, are a reminder that Duchamp remained fascinated by mechanical processes.

A video of the work that became a major obsession, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), is screened onto the wall, a conceit the artist would have appreciated.

This complex exploration of art and logic, which uses a window-like frame to draw viewers into its complexity, continues to mystify and intrigue viewers. It is in Philadelphia as a permanent installation, embedded in concrete. In 1923 after declaring it to be “definitively unfinished”, Duchamp announced he was abandoning art for chess. Some years later, after the work’s glass panels were broken in transit, he put the shattered pieces together, and declared it complete.

He said, “I didn’t want to pin myself down to one little circle, and I tried at least to be as universal as I could. That is why I took up chess.” Chess was to remain a lifelong obsession but Duchamp’s claim to have abandoned art was, of course, untrue.

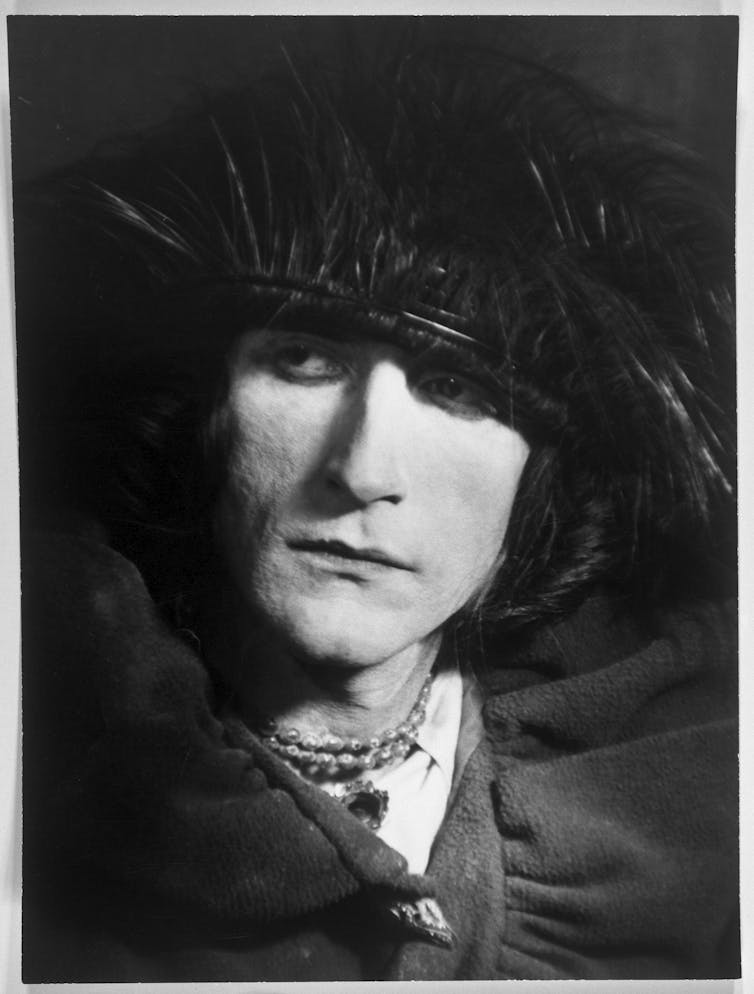

He reappeared in drag as the poet and artist Rrose Sélavy who created word games, puzzles, poetry and a distinctively designed perfume bottle, Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette. The artist would not be confined.

Duchamp’s art and iconoclasm echoes throughout the generations. It triggered the self-mockery of Pop art, the harsh purity of Op art, the intellectual rigour of Conceptualism. In 1967 the Auckland City Art Gallery negotiated an exhibition by Duchamp from a private collection. This exhibition empowered a new generation of artists, critics and curators in both New Zealand and Australia.

When he considered the nature of art and fame, Duchamp told the curator Sweeney of how his dentist had failed to bank a cheque used to pay his account, preferring instead to collect the artefact with its famous signature.

Duchamp bought the cheque back from the dentist and added it to his own collection. In the end, an artist’s reputation depends more on those who see the art than those who make it.

The essential Duchamp, organised by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is on view at the Art Gallery of NSW until August 11.

![]()

Joanna Mendelssohn, Honorary Associate Professor, Art & Design: UNSW Australia. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.