Viewpoints: could Labor's tax change make the system fairer or hurt investors?

Labor's plan to scrap cash refunds on unused franking credits could change the game for some investors in Australian companies.

Labor's plan to scrap cash refunds on unused franking credits could change the game for some investors in Australian companies.

The Australian Labor Party will scrap a system that refunds more than $5 billion a year to low or zero tax paying investors, should it win government.

“Franking credits” are designed to stop tax being paid twice on Australian corporate profits, allowing shareholders a credit for the tax paid by the company. But when shareholders don’t pay taxes at all they can claim a cash refund for unused credits from the tax office.

Scrapping cash refunds on unused franking credits could make the tax system fairer, according to Danielle Wood, Brendan Coates and John Daley from the Grattan Institute.

But Gordon Mackenzie from UNSW says these cash refunds incentivise people to invest in Australian companies, and ending them could see superannuation funds and self-managed super funds, in particular, pulling their investment from local companies.

Labor proposes to abolish cash refunds of unused franking credits for individuals and superannuation funds. Not-for-profits and universities, which do not pay income tax, will continue to receive cash refunds for franking credits.

Danielle Wood, Brendan Coates and John Daley, Grattan Institute

Labor’s proposal is not comprehensive tax reform. But in the absence of that holy grail, it is a piecemeal move towards a more equitable tax system. The change will primarily affect wealthy retirees.

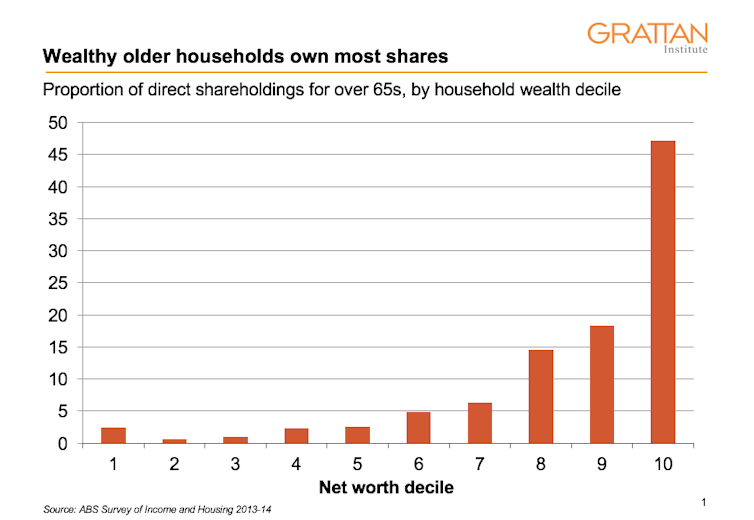

The wealthiest 20% of retirees own 86% of shares held by older Australians outside of super. And among self-managed superannuation funds (primarily held by wealthier retirees), half of the refunds are currently going to people with balances over $2.4 million.

Abolishing cash refunds for individuals and superannuation funds will raise about $5 billion a year in extra revenue. About 33% will be paid by individuals (mostly in high wealth households), 60% will be paid by self-managed superannuation funds (typically held by wealthier retirees), and the remaining 7% will be paid by Australian Prudential Regulation Authority regulated superannuation funds.

At the time, the decision cost the budget little – around $550 million a year – because very few people with low income also owned shares.

But new superannuation rules in 2006 relieved retirees from paying any tax on their superannuation withdrawals. Retirees also pay no tax on their super fund earnings. As more people with significant super balances retire, an increasing number qualify for cash refunds on unused franking credits.

And a series of changes to the Seniors and Pensioners Tax Offset increased the proportion of over-65s paying no tax on earnings outside of super.

The cash refund system now costs the federal budget more than $5 billion a year. But abolishing cash refunds on dividends won’t be costless.

The franking credit regime was set up for a variety of good reasons. It aimed to bias Australians towards investing in Australia. In practice this appears to have led to Australian companies being funded more through equity and less through debt, improving financial stability.

In theory it would also lead to more physical investment in Australia, although there is less evidence this has happened.

In practice, franking credits also encourage Australian companies to pay dividends rather than inefficiently hoard cash or invest in low-return projects.

So abolishing cash refunds, but keeping franking credits for those who do pay income tax, is probably not the ideal policy. It abandons the principle that all company profits should be taxed at an investor’s marginal rate of income tax. And it reduces the incentive for retirees to invest in companies from Australia rather than overseas.

On the other hand, the decisions not to tax superannuation withdrawals and to increase the effective tax-free threshold for older Australians have led to wealthy retirees contributing very little to government revenues relative to younger households.

Even though the wealth of older generations has jumped in line with asset prices, the share of senior Australians who pay income tax has nearly halved – from 27% to 16% – in the past two decades.

In an ideal world the federal government would reintroduce a number of higher income and wealthy older Australians to the tax system by taxing superannuation earnings and abolishing age-based tax rates. But in the absence of the political will to make these changes, abolishing cash refunds provides a big boost to the budget bottom line from more or less the same group.

Gordon Mackenzie, Senior Lecturer, UNSW

Chasing franking credits is one of the few tax issues that super fund investment managers take into account when investing, and is a significant consideration for self-managed super funds, according to my research with Professor Margaret McKerchar.

As the previous authors mention, franking credits are intended as an incentive for certain investors to invest in Australian companies. Under the rules, super funds and self-managed super funds don’t pay tax when they are paying a retirement pension, if the account balance is below a certain level.

Since they pay no tax, it is worthwhile for these funds to invest in Australian companies that will pay franking credits. Doing so allows them to claim credits from the tax office.

But this also means that if cash refunds on franking credits are done away with, it is an implicit 30% tax increase on super and self-managed funds that invest in Australian companies. This creates an incentive for them to put their money elsewhere.

If these funds invest in something like a government bond then they will pay no tax on the profits. If they invest in an Australian company, the company will pay the corporate tax and there will be no way for super funds to claim the tax back.

Many self-managed super funds have accounts for paying a pension to the member and another account for accumulating funds, but not paying out anything. Self-managed super funds will likely replace Australian shares in their pension accounts with assets such as bonds or managed funds.

This is important, as data shows that Australian shares are one of the largest asset classes held by self-managed super funds, ranging between 21% and 30.8% of the entire portfolio, depending on the size of the fund.

The response of other types of superannuation funds will probably be more muted. While they do value imputation credits, they also care about diversifying their portfolios - there will still be benefits to holding some Australian shares.

![]() Overall, then, imputation credits are important to superannuation funds, both big and small. The refund not only makes certain types of investment attractive, but also drives how much is invested in that type of investment.

Overall, then, imputation credits are important to superannuation funds, both big and small. The refund not only makes certain types of investment attractive, but also drives how much is invested in that type of investment.

Danielle Wood is the Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutions at the Grattan Institute; Brendan Coates is a Fellow at the Grattan Institute; John Daley is the Chief Executive Officer of the Grattan Institute; and Gordon Mackenzie is a Senior Lecturer at UNSW.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.