A new species of marsupial lion tells us about Australia’s past

The discovery of a new species of marsupial lion in north-west Queensland provides important insight into what habitats were like in the past, writes Anna Gillespie.

The discovery of a new species of marsupial lion in north-west Queensland provides important insight into what habitats were like in the past, writes Anna Gillespie.

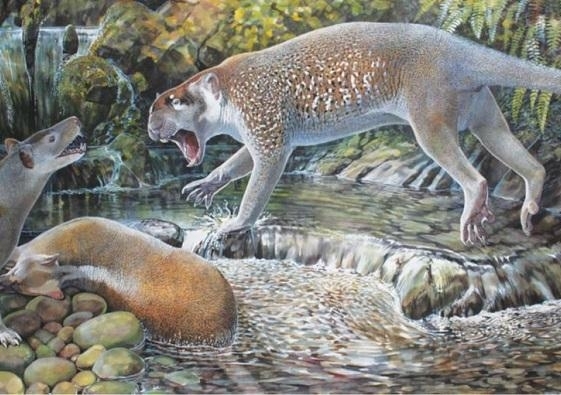

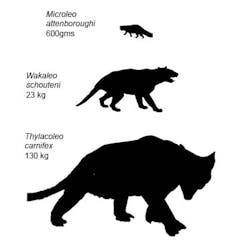

OPINION: My colleagues and I have discovered a new species of marsupial lion, Wakaleo schouteni, from the Riversleigh World Heritage Area in north-west Queensland. The species was the size of a Collie dog and weighed about 23 kilograms.

Fossils of this species include a beautifully preserved skull, jaws and upper arm bones. These were recovered from sites that have been dated at around 18 million years old (a period known as the early Miocene), and from others that are estimated to be older (the late Oligocene period, approximately 23 million years old).

“Marsupial lions”, also known as thylacoleonids, are an extinct family of marsupials that were present in Australia from about 24 million years ago up until the end of the Pleistocene era, about 30,000 years ago.

Their distinguishing feature is the presence of lengthened premolar teeth that form a pair of secateur-like blades. This feature – massively developed in the most recent member of the family, Thylacoleo carnifex – led to them being named a “marsupial lion” by the 19th-century palaeontologist Sir Richard Owen.

At present, the thylacoleonid family contains nine species, five of which belong to the genus Wakaleo.

Previously, species of Wakaleo were known from younger sites that spanned the middle Miocene to the late Miocene era, dating to approximately 17 to 5 million years ago. These species were roughly dog-sized and appeared to have formed a morphocline – that is, a series of animals with certain features that gradually evolved over time, with each species being sequentially replaced. The Wakaleo species increased in size over millions of years.

These species were distinguished from other marsupial lion species by loss of the front premolar tooth or teeth. However, the newly found Wakaleo schouteni species retains these premolars, indicating that the earlier members of the genus had features that were more primitive.

This feature was shared with another marsupial lion from around the same period: Priscileo pitikantensis from central Australia. It was possible that this relatively poorly preserved species may have been actually a species of Wakaleo.

Our new study undertook a review of that specimen and found similarities of its molars and humerus (the upper-most bone of the upper limb) with those of W. schouteni, confirming that it was a species of Wakaleo (now Wakaleo pitikantensis).

The skull of Wakaleo schouteni is around 16.5cm long. Shown below, at the left end is the nose, and most of the face. In the middle is the cheek bone (which is incomplete) and the socket for the eye, and at the right end is the brain case.

The new species of Wakaleo from Riversleigh differs from the central Australian Wakaleo in being slightly larger and differing in the morphology of the shoulder-end of the humerus bone. In anatomy, “morphology” is a term that describes the appearance and the structure of a part of the body.

These differences in the humerus suggest that the two species moved their arms slightly differently – we’re looking at this closely now as part of our ongoing research.

The fossils that we find in a region can tell us a lot about what habitats were like in the past.

On the basis of the diversity of the mammals recovered from Riversleigh, the region in the late Oligocene and early Miocene Australia is believed to have been forested. We think the earlier period (approximately 23 million years old) had relatively open forests, and the later period (around 18 million years old), more closed forests, possibly rainforests.

It is highly likely that Wakaleo schouteni pursued its prey – small vertebrates like lizards, frogs, birds and small mammals – through the tree-tops of these forests.

Given the apparent changes over time we’ve seen within the Wakaleo species of marsupial lion, it is possible that the slightly smaller species from central Australia may be slightly older than the larger Wakaleo schouteni.

Alternatively, these animals may represent what is known as allopatric species: this means they evolved separately due to geographic isolation.

![]() Whatever the scenario, this new findings push the origins of the Wakaleo genus back into the late Oligocene period, around 23 millions years into Australia’s past, and point to even earlier origins for marsupial lions than we had previously thought.

Whatever the scenario, this new findings push the origins of the Wakaleo genus back into the late Oligocene period, around 23 millions years into Australia’s past, and point to even earlier origins for marsupial lions than we had previously thought.

Anna Gillespie is a Technical Researcher at UNSW.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.