NBN and Mr Fluffy overreach remind us why governments should lead, not command

When governments overpromise or overreact, we all bear the costs, writes Jenny Stewart.

When governments overpromise or overreact, we all bear the costs, writes Jenny Stewart.

OPINION: The world is a more complex place than it used to be, and it's generally accepted that governments need to work more flexibly than in the past. It's all the more surprising, then, that, in the case of the national broadband network, Australian governments have opted for an old-fashioned, top-down, high-cost solution to the problem of providing all Australians with access to high-speed broadband.

NBN Co, a government-owned infrastructure company, owns most of the necessary cabling, on-selling capacity to internet service providers. In an environment characterised by very fast-moving technologies and markets, NBN risks being overtaken by events.

It's little wonder consumers are unhappy because, in many instances, we will be compulsorily transferred to the NBN-based model. In areas where internet services were poor, consumers are probably happy with the result. But many parts of large cities were wired up years ago, with various combinations of optical fibre and copper wire from the node to home. Consumers in these situations, with established relationships with their providers, face a period of some confusion as they sort out a bewildering array of services and packages.

All this is happening because, to do its job, NBN Co plays a monopoly role, which means other telcos cannot compete with it directly. It used to be the Australian way to set up a public corporation to provide infrastructure. But Telstra, whose predecessor installed all the copper wiring upon which the original phone system was based, was privatised years ago. Deregulation over the years opened up the network to other telcos (such as Optus, itself a privatised government-owned carrier). There were still opportunities for the public sector. In the case of the ACT, internet connections were installed by Transact, a territory-owned corporation whose network was eventually bought by iiNet.

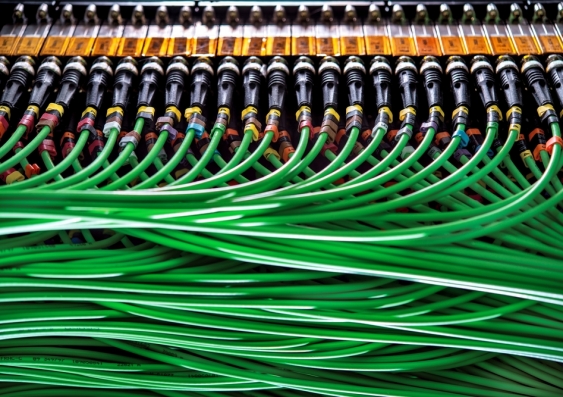

Photo: Shutterstock

With so much activity already under way, you would think that building on these beginnings so that all Australians enjoyed a satisfactory broadband service would be the way to go. Infrastructure in the 21st century needs to be more decentered and flexible than in the past. By moving in the opposite direction, Australian governments have created far more difficulty and expense than would otherwise have been the case. There is also the issue of compulsion. The NBN-based model means that many existing cable-broadband consumers are forced into a service framework they did not choose, and which might not deliver the services they want. Expect many more complaints to the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman.

State and territory governments are even more likely than the federal government to reach for the big gun of compulsion rather than undertake the harder tasks of negotiation and compromise. The ACT government's response to the problem of asbestos in residential buildings is an interesting case in point. For those unfamiliar with the story, beginning in 1988, a major Commonwealth-funded program was initiated to remove or encapsulate loose-fill asbestos in every Canberra home known to contain this dangerous material. In the ensuing years, many home owners went further and obtained reports from qualified inspectors as to the safety of their properties. Then, in 2014, a house that was missed in the 1990s program was found to contain asbestos in a rather dangerous condition.

Photo: Shutterstock

This time, the government decided to buy back all the houses from their owners (1022 in all), demolish them and resell the blocks. Home owners effectively had no choice. They either accepted the government's offer or continued on their own. As a result, some of the prettiest houses in Canberra have disappeared, the ground where they stood scraped bare. It's nice to see that at least some of the gardens were retained, although how many of the trees will survive the redevelopment process remains to be seen.

Why this drastic, one-size-fits-all solution? The risk had not changed but the politics had. Some of the asbestos-affected home owners formed a very effective lobby group, which changed everything. There was a panic about asbestos. Asbestos had all the attributes of dread: unseen, deadly, somehow dirty. People owning "Mr Fluffy" houses, no matter how minimal or how safely contained the asbestos risk, were obliged to put up signs outside their houses advising there could be health risks from entering their premises.

How many lives were saved as a result of the mass demolition? Probably none.

The net cost to ACT taxpayers of the mass-demolition response is estimated to be about $350 million. That's a lot of money for a small jurisdiction. How many lives were saved as a result? The answer: probably none. Those at most risk needed to be rehoused. But in most cases, the asbestos had been adequately dealt with years before and home owners were happy with the result. Unfortunately, by 2014, the politics of the situation meant they were to be given no choice as to the fate of their much-loved homes and gardens.

As with any carcinogen, risk is exposure-related. Little could be done about those who had been exposed to the real risks: the tradies who had installed the asbestos and unknowingly worked on contaminated properties since. For those with contained asbestos in their roofs, the extra risk (above the background level of asbestos exposure we all share) was almost impossible to quantify.

The ACT government knew how complex the situation actually was. Indeed, the comparatively relaxed attitude that was displayed in 2017, when asbestos was found in commercial premises above a pub, suggests how political the issue had become. Was the government afraid of being sued? Even if it was, it is difficult to envisage a payout greater than the sum spent. The Commonwealth, which ran the ACT when the 1989 testing was done, simply walked away from its own responsibility, agreeing only to lend the ACT government the clean-up money.

As Australians, we have high expectations of our governments. Far more than Americans, for example, we expect that, if we have a problem, the "government" should do something about it. It is how far this responsibility goes, and how it should be discharged, that is the issue. When governments overpromise and underdeliver, or overreact, we all bear the cost.

Professor Jenny Stewart is a visiting fellow in UNSW Canberra's School of Business.

This article was originally published in the Canberra Times.