Get ready for an Australian astronaut

The announcement that Australia will finally create its own space agency has opened the door for a long-held dream for many: a home-grown Australian astronaut.

The announcement that Australia will finally create its own space agency has opened the door for a long-held dream for many: a home-grown Australian astronaut.

The announcement that Australia will finally create its own space agency has opened the door for a long-held dream for many: a home-grown Australian astronaut.

“Until now, anyone wanting to become an astronaut had the odds stacked against them,” said Andrew Dempster, Director of the Australian Centre for Space Engineering Research (ACSER) at UNSW Sydney. “They had to become citizens of a another country, like the US, and then work hard to get into a space agency like NASA. That won’t be the case any more: in fact, the first home-grown astronaut may only be years away. And he or she has probably been dreaming about this for years.”

Two Australian-born astronauts, Paul Scully-Power and Andy Thomas, have flown into space but both had to become US citizens to do so. Scully-Power, from Sydney, was an oceanographer who flew as a payload specialist in 1984 while working for the US Naval Undersea Warfare Centre; Thomas, from Adelaide, is an aerospace engineer who served as a NASA astronaut on shuttle missions from 1996 to 2005.

An Australian space agency would allow Australians to train and fly as astronauts but, more importantly, it would also coordinate national efforts and act as the central contact point for nation-to-nation requests for collaboration in space missions and projects. When such requests come now, they are often passed on to Geoscience Australia, the CSIRO or the Bureau of Meteorology, which are world-class users of space facilities but largely unqualified in building, launching and operating in space.

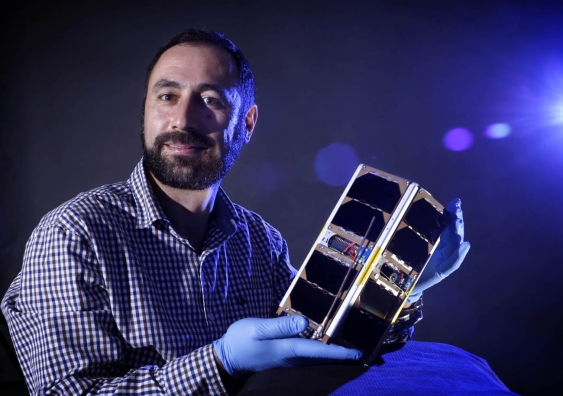

Dr Elias Aboutanios, Deputy Director of ACSER, holding the UNSW-EC0 cubesat before its launch. Photo: Grant Turner/UNSW

“We’re responsible for one-eighth of the world’s surface in meteorology and air traffic control, and we’ve got the second-lowest population density in the world, so space is probably more important for Australia than virtually any other country,” said Dempster. “In the civilian sphere, Australia should be number one in space, but we’re just nowhere near that.

“The good news is that the nature of the space industry is changing. We’re moving into an era where access to space is cheaper and easier than ever before. We don’t need big, clunky space agencies and giant satellites – we can skip all that and move straight to this more dynamic, disruptive environment. And we're already doing that.”

In April, three Australian satellites – the first in 15 years – blasted off from Cape Canaveral and were deployed in May from the International Space Station. Two were built at ACSER: UNSW-EC0 and INSPIRE-2 (the latter a joint project with the University of Sydney and the Australian National University). The third, SuSAT, was built by the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia.

Each of the "cubesats" is the size of a loaf of bread and weighs less than 2 kg, and will carry out the most extensive measurements ever undertaken of the thermosphere. This region, between 200 and 380 km above Earth, is a poorly studied zone that is vital for communications and weather formation.

ACSER also built space GPS hardware and software for Project Biarri, a cubesat mission by Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Group that is part of the Five Eyes defence agreement with Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. The satellite was also launched this year.

“We’ve got more hardware in space today than Australia’s had in its history,” added Dempster, who is also a member of the advisory council of the Space Industry Association of Australia. “This shows what we can do in Australia in the new world of ‘Space 2.0’, where the big, expensive agency-driven satellites are being replaced by disruptive low-cost access to space.

"Having a space agency isn’t about spending loads of money on giant satellites. We can build constellations of small satellites for probably less than it costs to build one big satellite. So it's a completely different business environment and there is a lot of investment in the area. The cubesat side of the business is growing at 20% a year,” he added.

Australia’s space industry is estimated to be worth $US3-4 billion and employs about 11,500 people. “But we need a space agency to grow this,” said Dempster. “We’ve got only 2% of the global space market, but we should have 4% based on Australia’s proportion of global GDP. So there’s a real opportunity there, because we have the skills and there are Australian companies operating in this area, but no national coordination.”