Architecture can help solve poverty, inequality, segregation

2017-07-27T16:03:00+10:00

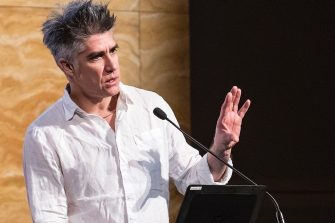

Pritzker Prize winning architect Alejandro Aravena says architecture students should be encouraged to apply their training to the challenges facing society.

Pritzker Prize winning architect Alejandro Aravena says architecture students should be encouraged to apply their training to the challenges facing society.

Speaking at a press conference on the 47th floor of Australian architect Harry Seidler’s iconic Australia Square Building ahead of his C+A Talk at UNSW Built Environment, the 2016 recipient of the architecture profession's highest honour discussed the role architects can play in solving global challenges.

“The problems in the world are poverty, inequality, segregation,” he said. “Architects have the skills to deal with these issues if they listen to all the forces at play.”

The 48-year-old Chilean architect is best known for his work with "do tank" Elemental, an architecture group that aims to alleviate poverty and eliminate slums using a participatory approach that engages local communities in the early stages of the design process.

As executive director of Elemental, Aravena first attracted international attention in 2004 for the Quinta Monroy development in Iquique, Chile. The scheme was designed to create low-cost housing by building the frame and the essential rooms for each house, leaving the remainder for residents to complete themselves over time.

Architecture is about finding imaginative, creative solutions to improving people’s quality of life.

The group also played a focal role in the rebuilding of Constitución, one of the towns that was almost destroyed by the 2010 Chilean earthquake and subsequent tsunami.

Aravena described the complexities of working in complex, political environments and how he re-educates himself every time he works on a new project.

“I still appreciate, value and use the training I was given, but what I don’t see in architecture education now is how to apply that training to the challenges of society.”

By challenges, Aravena is referring to the pressing need for social housing globally, with three billion people now living in cities and a third of them living below the poverty line.

“Architects need to understand people and places and be able to read between the lines,” he said. “Communication is only 90 percent verbal – we need to be face to face to fully communicate. We have access to sophisticated technology but it’s completely mismatched to the primitive emotions humans have been dealing with for millennia; fear, desire, love and envy.”

This philosophy informed the theme of the Venice Architecture Biennale which Aravena curated last year. Called Reporting From the Front, the exhibition aimed to address global issues including crime, sanitation, housing shortage, traffic, waste, migration and pollution.

Aravena said architecture’s potential to alleviate some of the world’s problems comes from a balance between practicality and intelligence.

“Architecture is about finding imaginative, creative solutions to improving people’s quality of life. Our job is to gather knowledge from an often friction-filled set of constraints and restrictions and extract lessons from that.”

Aravena is often described as a ‘humanitarian’ or ‘activist’ architect but he says all forms of architecture have a beneficial role to play.

Gesturing out across the Sydney skyline he said there is no difference between designing a high rise or social housing, in terms of their contribution to the public good.

“If a glass tower is designed in an intelligent and sustainable way that saves resources you can address huge problems for society – just as many as dealing with a poor community that doesn’t have shelter over their head. It’s not about being more, or less, humanitarian. The built environment is a complex challenge and we can address that challenge on many different levels.”

Aravena closed the press conference by stating that rather than architecture being presented as a profession, it should be seen as a set of tools to understand society.

“You may end up designing buildings with your training, or you may use your degree as a way to understand reality, and given the global challenges we are dealing with, that is also desirable.”

UNSW Built Environment Dean Professor Helen Lochhead said the Social Agency stream in the Architecture program recognises the imperative for UNSW graduates to use their skills to address the broader urban challenges of our cities.

“This is where there is the greatest need and greatest potential to have a significant impact on people’s lives globally.

“Projects such as Aravena's low income housing model have achieved a real step change in social housing by not only providing basic shelter but giving people capacity to improve their homes, while enhancing their equity and potential to move up and out of the poverty cycle," Lochhead said.

UNSW Professor of Practice Glenn Murcutt is also a Pritzker Prize winner. In 2002 Murcutt became the first, and only, Australian to be awarded the Pritzker, widely regarded as the Nobel Prize of architecture. In 2010 he joined other high-profile international architects as a Pritzker Prize jury member and was appointed chairman of the jury last year.

UNSW Built Environment is a partner of the C+A Talks series which operates in conjunction with the iconic C+A magazine by bringing architects of distinction to Australia as CCAA guests to address Australian audiences.

Media enquiries

Fran Strachan

Communications Manager Low Carbon Living CRC

Tel: +61 2 9385 5402

Email: fran.strachan@unsw.edu.au