Fossils discovered by UNSW scientists in 3.48 billion year old hot spring deposits in the Pilbara region of Western Australia have pushed back by 580 million years the earliest known existence of microbial life on land.

Previously, the world’s oldest evidence for microbial life on land came from 2.7- 2.9 billion-year-old deposits in South Africa containing organic matter-rich ancient soils.

“Our exciting findings don't just extend back the record of life living in hot springs by 3 billion years, they indicate that life was inhabiting the land much earlier than previously thought, by up to about 580 million years,” says study first author, UNSW PhD candidate, Tara Djokic.

UNSW PhD student Tara Djokic in the Dresser Formation in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia. Photo: Dale Anderson

“This may have implications for an origin of life in freshwater hot springs on land, rather than the more widely discussed idea that life developed in the ocean and adapted to land later.”

Scientists are considering two hypotheses regarding the origin of life. Either that it began in deep sea hydrothermal vents, or alternatively that it began on land in a version of Charles Darwin's "warm little pond”.

“The discovery of potential biological signatures in these ancient hot springs in Western Australia provides a geological perspective that may lend weight to a land-based origin of life,” says Ms Djokic.

“Our research also has major implications for the search for life on Mars, because the red planet has ancient hot spring deposits of a similar age to the Dresser Formation in the Pilbara.

“Of the top three potential landing sites for the Mars 2020 rover, Columbia Hills is indicated as a hot spring environment. If life can be preserved in hot springs so far back in Earth’s history, then there is a good chance it could be preserved in Martian hot springs too.”

The study, by Ms Djokic and Professors Martin Van Kranendonk, Malcolm Walter and Colin Ward of UNSW Sydney, and Professor Kathleen Campbell of the University of Auckland, is published in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers studied exceptionally well-preserved deposits which are approximately 3.5 billion years old in the ancient Dresser Formation in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia.

L-R: Tara Djokic and Professor Martin Van Kranendonk in the Pilbara in Western Australia. Photo:Kathy Campbell

They interpreted the deposits were formed on land, not in the ocean, by identifying the presence of geyserite – a mineral deposit formed from near boiling-temperature, silica-rich, fluids that is only found in a terrestrial hot spring environment. Previously, the oldest known geyserite had been identified from rocks about 400 million years old.

Ridges in the ancient Dresser Formation in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia that preserve ancient stromatolites and hot spring deposits. Picture: Kathleen Campbell

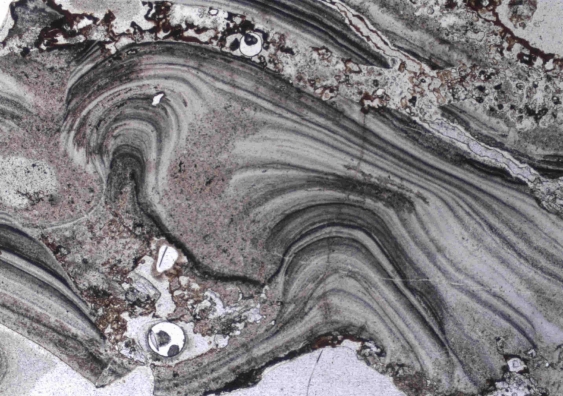

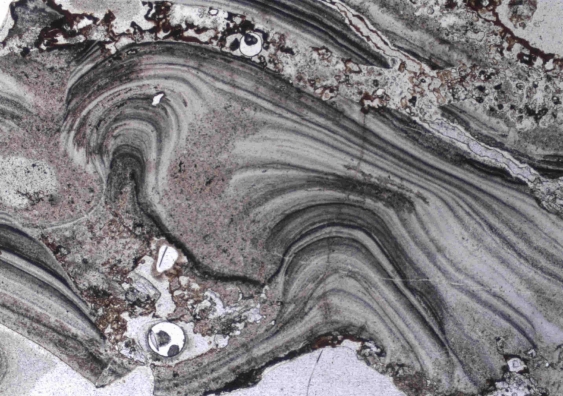

Within the Pilbara hot-spring deposits, the researchers also discovered stromatolites – layered rock structures created by communities of ancient microbes. And there were other signs of early life in the deposits as well, including fossilised micro-stromatolites, microbial palisade texture and well preserved bubbles that are inferred to have been trapped in a sticky substance (microbial) to preserve the bubble shape.

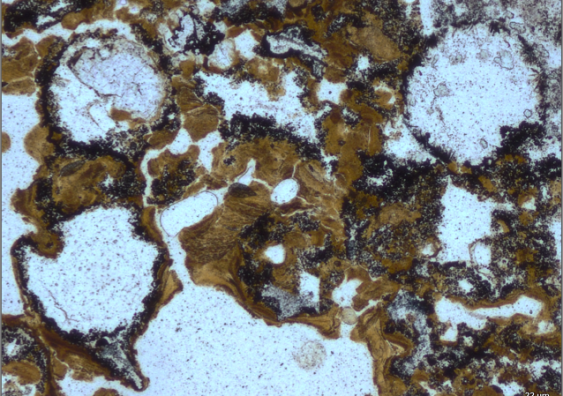

A microscopic image of geyserite textures from the ancient Dresser Formation in the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia. This shows that surface hot spring deposits once existed there 3.48 billion years ago. Photo: UNSW

“This shows a diverse variety of life existed in fresh water, on land, very early in Earth’s history,” says Professor Van Kranendonk, Director of the Australian Centre for Astrobiology and head of the UNSW school of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“The Pilbara deposits are the same age as much of the crust of Mars, which makes hot spring deposits on the red planet an exciting target for our quest to find fossilised life there.”

Watch a BBC TV interview with Professor Van Kranendonk in the Pilbara here.

A modern day geyser erupting at Geysir Hot Springs in Iceland. Photo: Tara Djokic

In September 2016, Professor Kranendonk was part of an international team that found what is possibly the oldest evidence of life on Earth – 3.7 billion-year-old fossil stromatolites in Greenland deposits that were laid down in a shallow sea. He has also given geological advice to NASA on where to land the rover on the 2020 Mars Exploration Mission.

“The Pilbara provides us with a rich record of early life on Earth and is a key region for developing exploration strategies for Mars to try and answer one of the greatest enigmas in science and philosophy – did life arise more than once in the universe?” says Professor Walter, founding director of the Australian Centre for Astrobiology.

“That’s why we are working to gain World Heritage listing for its main fossil sites.”

Professor Walter, AM, will give a lecture on the search for life on Earth and Mars at UNSW, on Wednesday 17 May at 6 pm in the Scientia Building. Registration is essential.

Professor Martin Van Kranendonk and Tara Djokic at Lake Rotokawa in New Zealand studying modern hot springs. Photo: Kathleen Campbell