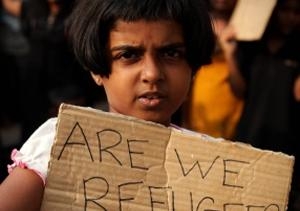

One step forward, two steps back for asylum seeker mental health

Current immigration policies regarding asylum seekers promote uncertainty, fear and disempowerment, which contribute to mental illness, argues Belinda Liddell.

Current immigration policies regarding asylum seekers promote uncertainty, fear and disempowerment, which contribute to mental illness, argues Belinda Liddell.

OPINION: The recent overhaul of Australia’s immigration policies aims to protect the lives of asylum seekers by removing any advantage of arriving by boat. Whether this goal will be achieved remains unclear. But while we wait for an answer, we need to consider the toll of Australia’s immigration policies on the mental health of asylum seekers.

In Nauru, where more than 380 asylum seekers are currently being detained, there have been reports of hunger strikes, self-harm, aggression and suicide attempts.

Unfortunately this isn’t new – these signs of psychological distress have been repeatedly witnessed in Australia’s immigration detention centres since the early 1990s.

For several decades now, mental health professionals have documented the psychological health of asylum seekers within mandatory detention facilities. Findings from multiple studies provide clear evidence of deteriorating mental health as a result of indefinite detention, with profound long-term consequences even after community resettlement.

Current immigration policies continue to promote uncertainty, fear and disempowerment among asylum seekers, which are known to contribute to poor mental health. There are also concerns that allowing asylum seekers to live in the community on bridging visas without the right to work could further exacerbate these feelings of helplessness.

Compounding trauma

Asylum seekers are already vulnerable to mental distress before arriving in Australia. Significant exposure to potentially traumatic incidents, including gross human rights violations, persecution, conflict, forced displacement and family separation, are common.

Being detained as part of the process of seeking asylum can actively compound existing mental suffering. Rates of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide and self-harm are much higher among detained asylum seekers compared with compatriots in community settings.

One primary stressor that systematically undermines the mental health of asylum seekers is the pervading sense of uncertainty within mandatory detention. Visa processing times are often unknown, as are visa status outcomes. There is ambiguity about the duration of detention and barriers to family reunification. Asylum seekers also worry about the safety of family members and have doubts about whether they’ll be able to assimilate into the Australian community.

Other stressors that continue to undermine asylum seeker mental health within detention include reduced self-determination and autonomy, and physical and cultural isolation from family, friends and community. These factors, among others, can combine to fuel a pervasive helplessness that is commonly reported by detained asylum seekers.

Ongoing situational stress, such as being in an unfamiliar, poorly resourced environment, as well as living among other distressed individuals, does little to provide the safe and secure environment necessary to support recovery from traumatic stress.

Bridging visas

Bridging visas may be a welcome avenue for some asylum seekers to reside within the Australian community while their refugee applications are processed.

Asylum seekers living in the community commonly present to health services with mental health problems, but research has shown symptoms to be less severe compared with detained asylum seekers.

But critically, some of the key stressors fuelling mental distress in detention will not be addressed by bridging visas. These include uncertainty about the projected five-year waiting period to determine visa status, and powerlessness associated with restricted work and financial support entitlements.

Insights can be drawn from research into the mental health impacts of other restrictive visa policies such as the temporary protection visa (TPVs) program. Research shows TPV holders faced much greater challenges settling into the community than refugees on permanent visas. They were also more worried about their uncertain residency status and reported greater living difficulties.

Over a two-year period, TPV holders demonstrated less English proficiency and were unmotivated to socially engage within their new community, thereby exacerbating isolation. This mix of factors can effectively dampen any hope for convalescence from mental health problems, even while residing in the community.

The concern is that bridging visas could impact on the mental health of asylum seekers in a similar way to TPVs. Additional research is needed to understand the effects of bridging visas on mental health.

Next steps

What can be done to reduce the impact of immigration policies on the mental health of asylum seekers?

The most straight-forward approach is to avoid policies that already have an evidence base of harm, including indefinite mandatory detention and restrictive visas such as TPVs.

New policies need to support asylum seekers to rebuild their psychological health. Within the current policy framework, strategies could be implemented to mitigate the impact of known detrimental factors. Asylum seekers on bridging visas, for example, could be permitted to work. And within detention facilities, asylum seekers could have greater access to legal resources to actively participate in their visa application process.

Ultimately, we need to adopt policies that harmonise immigration and national security priorities with strategies to protect the health and well-being of asylum seekers. This could prevent further damage, facilitate recovery from trauma, and pave the way for the positive integration of refugees into Australian culture and society.

Dr Belinda Liddell is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of Psychology at UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.