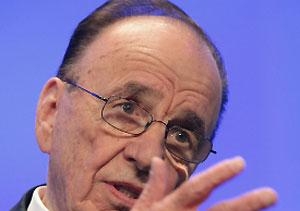

Gina Rinehart and Rupert Murdoch: a study of power in the media

The prospect of having all significant Australian newspapers controlled by just two individuals suggests a bleak outlook for the coverage of political debate, argues David McKnight.

The prospect of having all significant Australian newspapers controlled by just two individuals suggests a bleak outlook for the coverage of political debate, argues David McKnight.

OPINION: Australia’s wealthiest person, Gina Rinehart has bought shares in Fairfax Media. Should we be worried if she buys a controlling interest in the company that publishes the Age, Sydney Morning Herald and the Australian Financial Review?

I think we should.

It would mean that all the significant newspapers in Australia would be controlled by two very wealthy individuals, Rupert Murdoch and Gina Rinehart. In both cases, they bring with them an overarching political ideology which will inevitably affect their newspapers and through them, influence their readers.

This influence is not some comic book affair of the owner nightly dictating individual headlines and particular articles. Rather, owners choose editors and they in turn shape the coverage day in and day out.

In my recent book, Rupert Murdoch: an investigation of political power, I examine Murdoch’s relationship with his editors. I quote former Murdoch editor Eric Beecher who described Murdoch’s method as “by phone and by clone”.

Former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil described unpredictable and sudden phone calls from Murdoch, often punctuated by long silences. Neil also made the common sense point that Murdoch “picks as his editors people like me who are generally on the same wavelength as him: we started from a set of common assumptions about politics and society, even if we did not see eye to eye on every issue and have very different styles.”

David Yelland, an editor of the Sun, said Murdoch editors ultimately end up agreeing with everything he says. “But you don’t admit it to yourself that you’re being influenced. Most Murdoch editors wake up in the morning, switch on the radio, hear that something has happened … and think, ‘What would Rupert think about this?’”

One former News Corporation executive, Bruce Dover, described his editors’ behavior as a sort of “anticipatory compliance”. Another argued Murdoch is “less hands-on than people assume … It’s not done in a direct way where he issues instructions. [Rather,] it’s a bunch of people running around trying to please him.”

A similar kind of relationship between Gina Rinehart and her editors would almost certainly develop if she bought a controlling interest and was able to choose board members and senior management. The values and culture of the newsroom would evolve in response to this, with “difficult” journalists departing and the remaining ones understanding the limits of dissent and exercising self-censorship.

Murdoch and Rinehart are also similar in that their interest in the news media cannot be reduced to dollars and cents. Both see them as vehicles for exertion influence on public opinion. Rinehart’s investment in Fairfax cannot be explained in terms of seeking a dividend or profit. She has explained her interest in the news media because of “its importance to the nation’s future”.

On Murdoch’s part there have been multiple instances of him keeping unprofitable newspapers alive, largely for reason of influence. This is so in the case of the Australian, the Times and the New York Post.

Murdoch and Rinehart are both conservatives but of a quite different type. Murdoch’s was an early supporter of “small government”, low tax, deregulation and privatisation. After his Wall Street Journal purchase, his company ran a worldwide advertising campaign with the triumphant slogan, “Free markets, free people, free thinking”. Murdoch is a fervent supporter of US hegemony, symbolised by his global campaign in favour of Bush’s invasion of Iraq.

Rinehart is an Australian nationalist and follows a narrower self interest, including passionate opposition to new taxes for the mining industry. She supports “Special Economic Zones” in Australia’s north where temporary labour can be imported and mining companies can get tax breaks. One of her supporters in this quest is John McRoberts who was once also an adviser to Pauline Hanson. Murdoch’s papers campaigned against Hanson and her ideas.

But Murdoch and Rinehart are closer on the issue of climate scepticism. In 2011 her company Hancock Prospecting sponsored the Lang Hancock lecture at Notre Dame University in Western Australia which was delivered by the roving climate sceptic, Lord Christopher Monckton. In the case of Murdoch, he has now reverted to climate scepticism after momentarily issuing warnings about its “clear catastrophic threats”.

The agreement of both Murdoch and Rinehart on climate issues suggests a bleak outlook for the coverage and debate on climate in Australia’s two major newspaper networks.

Some see hope because, they say, newspapers are “legacy media”. But I think they are wrong. Newspapers still generate most original news. Most “online news” is produced either by newspapers or public broadcasters.

Newspapers employ the most journalists and enable specialist coverage of politics, health education and other areas. In particular, for historical reasons political coverage is central to newspapers in a way it isn’t for television, which produces entertainment not editorials. Most important of all, many academic research studies have shown newspapers are a decisive agenda-setter for radio and TV.

So both Gina Rinehart and Rupert Murdoch are right. They understand the nature of political power and the significance of newspapers. And we may be the worse off for it.

Associate Professor David McKnight is based in the Journalism and Media Research Centre.

This article was first published in The Conversation.