Bank bashing is a popular past-time. But is it justified?

The big banks in Australia are making record profits. Why? And where is that money going?

The big banks in Australia are making record profits. Why? And where is that money going?

With the recent close of reporting season for Australia’s listed companies, it was a bumper profit season for companies in many sectors, from energy and insurance, to banking and finance.

Australia’s big four banks, for example, reported a record full-year profit of nearly $32.5 billion between them (up 12.4 per cent compared to the previous financial year). The Commonwealth Bank posted the largest profit ($10.2 billion) followed by NAB ($7.7 billion), ANZ ($7.4 billion) and Westpac ($7.195 billion).

While the banks appear to be making fiscal hay while the interest rate sun shines, many mortgage holders are feeling the pinch of these increased interest rates. Recent Roy Morgan research, opens in a new window found that more than 1.5 million mortgage holders were at risk of mortgage stress in the three months to October 2023. This represents a significant increase with more than 700,000 more households at risk of mortgage stress after a year of interest rate increases. The RBA has revealed, opens in a new window that one in 50 mortgage holders could face severe financial stress.

Interest rate rises have a knock-on effect in the rental property market as well, with mortgage holders on investment properties passing on increases in bank repayments to renters. This is operationalised by how rates impact construction and supply. When property becomes more costly to build, less is built. And so, rents increase.

Rents across Australia have risen at the fastest rate in at least 15 years and more than 40 per cent of Australian house and unit markets have recorded double-digit rent increases, according to research from Corelogic, opens in a new window. However, a large portion of this does reflect a normalisation from the pandemic-era fall in rents in capital cities, and rent increases are dwarfed by increases in the costs of financing and owning property.

However, while interest rate rises represent glum news for mortgage holders, there are two sides to every coin when it comes to bank profits, according to Mark Humphery-Jenner, opens in a new window, Associate Professor in the School of Banking and Finance at UNSW Business School.

The banks’ surging profits are largely due to an increase in their profit margin on loans, which is called their “net interest margin”, said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner. This is the difference between the interest rate that banks pay for money (such as deposit rates) and what they receive when they lend the money (home mortgage rates).

This ‘net interest margin’ has dramatically widened for some sources of funds – such as deposits, said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner. For example, Westpac’s net interest margin rose 2 basis points (i.e., 0.02 percentage points) to 1.95 per cent. “While two basis points might not sound like much, when the bank handles billions of dollars it is significant,” he said.

More broadly, a key driver of net interest margins was the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) tightening of monetary policy – which increased these margins by an average of 9 basis points over the last financial year for the major banks. In combination with an increase in interest-earning assets of 7.3 per cent compared to the previous financial year, net interest income increased by 13.8 per cent to $74.9 billion for the big four banks.

Thus far, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, the RBA interest rate hikes have had a potentially positive impact on banks. “However, this could change,” he said. “The positive impact comes from the increase in what banks can charge for money. That is, banks are notorious for ‘passing on’ the RBA’s rate hike to their borrowers but not to their depositors.”

Some things partly mitigate this. For example, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, some people do put money into term deposit accounts. Others have noticed the low interest rates and shifted to ‘money market funds’ or have simply bought government treasuries (i.e., loaned money to the government rather than loaning it to the bank). “However, many Australians simply leave their money in a day-to-day account, which attracts low interest,” he observed.

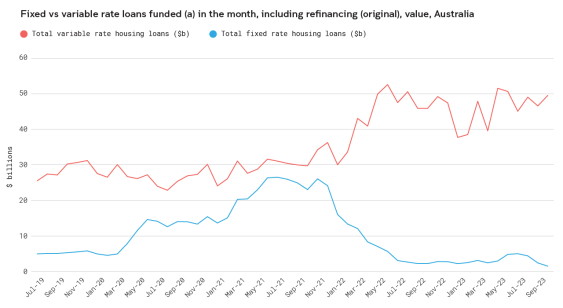

So far, customers have reportedly tolerated the mortgage rate increase (see below graphs), and A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner noted the mortgage cliff has not resulted in defaults – yet. “However, there will reach a point where customers with negative cash flow can no longer service a mortgage,” he said.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

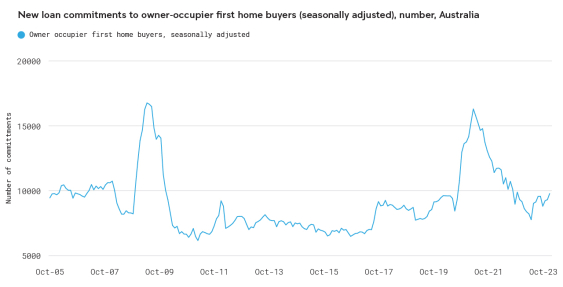

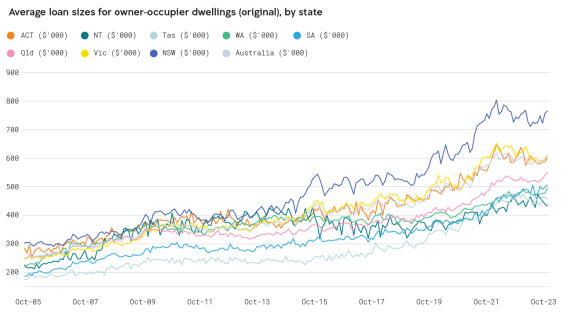

“If this only impacts a small number of customers, it is unlikely to harm the bank significantly. The bank can work with the customer to do an orderly sale of the property. Given current house prices (see below graph), the owner probably will earn a profit on the sale and the bank will be repaid. However, if many borrowers struggle, then banks could face increased delinquencies and recovery issues.”

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

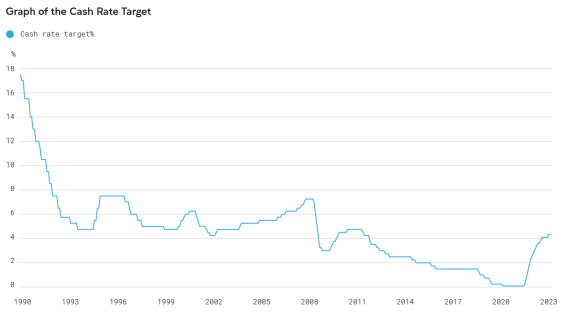

There has been much focus on interest rate rises from the RBA, which recently raised interest rates for the 13th time in 18 months, taking the cash rate to a 12-year high of 4.35 per cent. Banks have followed suit, with variable mortgage rates surging by 69 per cent since May 2022, when the cash rate was still at a record low of 0.1 per cent.

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

While rising interest rates often help bank profits, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said there are caveats, and the relationship is not straightforward. “When a bank lends money, it must obtain money from somewhere. Thus, the question is (a) how much can a bank charge when it lends, and (b) how much does the money cost the bank?” he asked.

When the RBA cash rate increases, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, banks typically ‘pass this on’ to customers, based on the argument that when the cash rate increases, so does the banks’ access to capital. “This is not always precisely true. But, it is well observed that if the RBA hikes by 25 basis points, then mortgage rates increase 25 basis points. In recent years, there has been mild disruption to this through competition. And this reflects the fact that when the RBA hikes by 25 basis points, bank funding costs do not increase by 25 basis points,” he said.

While the cost to banks of obtaining funds does increase when the RBA hikes rates, this is typically by less than the hike. In a purely efficient market, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, it should increase with the RBA hike. “In a perfect market, customers could simply take their money from a bank account, lend to the government risk-free at the cash rate, and earn more money,” said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner.

“But, this is typically an opaque process and can involve signing up to fund managers who earn large fees and can undermine the whole point of the process. People typically cannot simply log into their online trading platform and buy a government bond. Therefore, banks are slow to pass on RBA rate hikes to their depositors.”

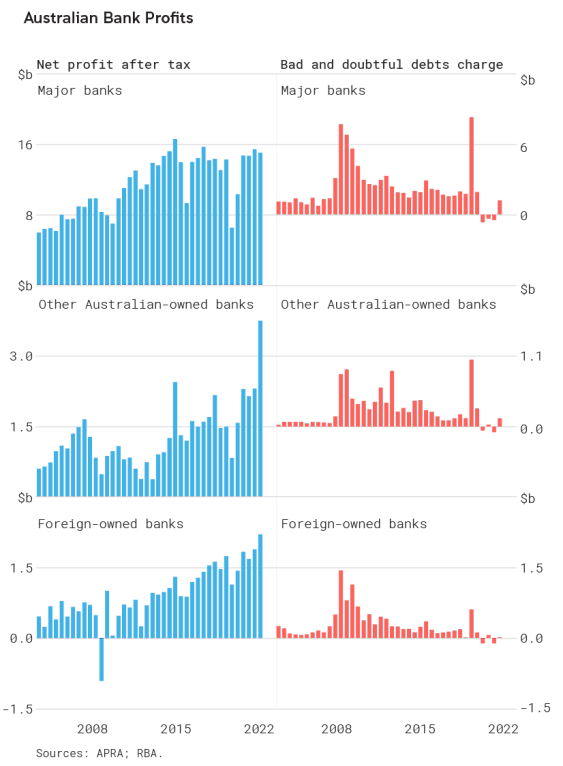

However, there is often some pass-through to term deposits. The net result is that the banks’ profit margins often increase when the RBA hikes rates – at least unless and until they face delinquencies and bad debts and/or a recession commences, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner noted.

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

As publicly listed corporations with shareholders, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, bank profits should belong to shareholders. However, as companies amass more cash holdings or large free cash flows, he noted there was a greater risk that managers spend the money on self-indulgent activities that neither benefit shareholders nor benefit customers. This can include pursuing causes or engaging in activism that does not align with their shareholders’ goals or their legal demands, which A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said was profit maximisation per the Corporations Act.

Major shareholders vary across the big four banks. Institutions own around 23 per cent of the shares of ANZ and Westpac, 18 per cent of CBA, and 27.7 per cent of NAB and 27.5 per cent of Macquarie. The largest institutional shareholder across the big four banks is The Vanguard Group – both directly and in addition to funds it controls, as well as through holdings in other fund managers (such as BlackRock and State Street, which also hold significant numbers of shares in Australia’s major banks).

A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner notes that many of these institutions hold on behalf of ‘everyday Australians’. “Thus, behind the institutional ownership is not a nameless faceless corporation, it is often ‘mum and dad’ investors,” said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner, who also observed many retail investors own shares in the big banks due to the role of compulsory superannuation.

By contrast, in the US, institutions such as Vanguard Group own 72.4 per cent of global financial giant J.P. Morgan. This reflects a variety of factors, including the greater prevalence of custodial brokers in the US. But, nevertheless, A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner said, this suggests that retail investors are more involved with Australian banks than they are with US banks.

A side note is that Australian banks are in a unique position, in that they are largely protected from significant competition,said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner. “In the US there are thousands of banks. In Australia, there are a handful. Thus, banks must avoid abusing their clear market power,” he asserted.

The net result is that Australians both gain and lose from big bank profits, according to A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner. “They gain through their superannuation and their stock holdings. After all, the big four banks will form a core part of any Australian superannuation fund,” he said.

However, Australians “do lose” if they have a mortgage (or are looking to get one). “Big bank profits deliver winners and losers. Many of the winners are everyday Australians. When people criticise bank profits but also want their superannuation to grow, they should consider whether they are implicitly criticising themselves: you can’t have it both ways,” said A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner.