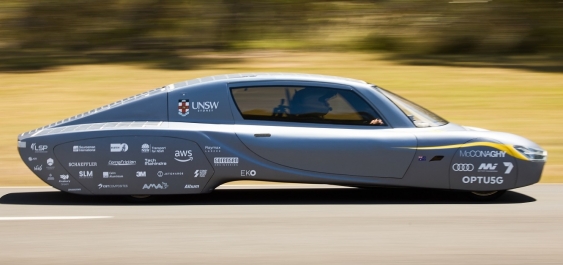

Record-breaking UNSW Sunswift 7 reaches for the stars in Bridgestone World Solar Challenge

UNSW student team will push more technological boundaries during epic 3600km race across Australia, but unfortunately it may be a last hurrah in the prestigious event.