UNSW Canberra researchers are drawing inspiration from nature to create the next generation of drones that could be used in fields as diverse as precision agriculture, search and rescue, and wildlife monitoring.

In an Australian Research Council-funded project, the research team – comprising Professor Matt Garratt and Dr Sridhar Ravi from UNSW Canberra and Professor Mandyam Srinivasan from the University of Queensland – is taking the vision-based flight-control strategies used by insects and applying them to miniature robotics systems. This will allow them to navigate autonomously in complex environments.

It follows a recent UNSW Canberra-led study that demonstrated how insects, such as bees, identify obstacles in their path and deftly avoid collisions.

Despite their tiny size, insects possess a remarkable ability to quickly assess their environment and dodge potential obstacles. Robotics expert Professor Matt Garratt explained that these are valuable characteristics for small robots.

“Insects appear to use simple lightweight methods to carry out obstacle avoidance whilst flying through narrow gaps and cluttered regions,” Professor Garratt said.

“We judge this because their brains are very small and they do not have stereo vision like larger animals such as humans.

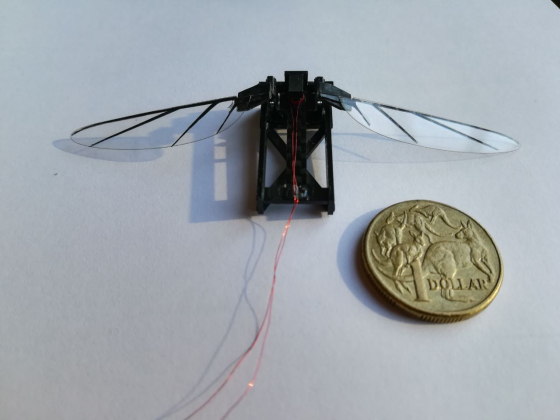

“We think these lightweight methods can run on small processors and tiny cameras placed on small robots like micro-air-vehicles to provide an autonomous navigation capability.”

Professor Garratt said small robots have several advantages. In addition to being able to pass through small spaces, their size makes them safer to operate as the impact of collision is significantly reduced.

They also use fewer materials and are more affordable to produce.

“We have confidence that the insect-inspired concepts will work because insects are so successful at autonomous flight themselves and clearly are not reliant on man-made infrastructure such as GPS,” Professor Garratt said.

He said many of the theories relate to optic flow or image motion and how the insects use that to judge obstacles.

“The basic idea is that something close by will move faster in the insect’s field-of-view than something further away,” he said.

“Once we have a hypothesis of how the insect is doing it, we can then go out and test that on a robot by programming in an equation that captures the hypothesis, or using something like a neural network, which has first been trained to do the task in a simulation.”

The aim is to produce robots that can safely navigate through tight spaces by themselves using only visual sensing and without additional infrastructure such as GPS.

“Conventional approaches use sensors like laser-rangefinders and radar, which can be heavy, expensive and sometimes dangerous because they emit radiation,” Professor Garratt said.

The practical applications are vast and varied. Small robots capable of navigating cluttered spaces could be applied to precision agriculture, search and rescue, package delivery, security patrol, environmental and wildlife monitoring, and film making.

As a multidisciplinary study, the project not only aims to contribute to robotics, but also provide insights into biological sciences – specifically animal behaviour.

“The project will seek to shed light on the salient sensory cues that underpin the behaviour and decision-making framework of animals when moving within the complex world,” Dr Ravi said.

Professor Srinivasan said the findings would be valuable to a range of fields.

“This funding from the ARC brings together a multidisciplinary team, comprising engineers and biologists, to create a synergy that will not only advance our understanding of animal vision and navigation, but also pave the way for the design of biologically inspired flying machines,” he said.