Vital Signs: Unemployment steady but needs to lower to lift wages

A tighter labour market than in the past is now needed to drive real wages growth.

A tighter labour market than in the past is now needed to drive real wages growth.

Thursday brought news that Australia’s official unemployment rate in January remained at a historically low 4.2 per cent In parliament, Prime Minister Scott Morrision boasted of the nation being on track to achieve a rate “with a 3 in front of it” this year.

It’s entirely possible the unemployment rate will drop further. The Reserve Bank of Australia’s central forecast is 3.75 per cent by the end of 2022. Some economists have suggested it could be driven down below 3 per cent.

With economic management is a key issue at any election, it is clear the state of the labour market will be a big part of the Coalitions re-election narrative.

But the story on wages is not impressive.

Real wages (that is, wages adjusted for inflation) have not grown strongly in recent years. From 2013 to 2018 they grew at 0.5 per cent, compared with 0.8 per cent from 2008 to 2012, and 1 per cent from 2001 to 2007.

Australia is not alone in this respect. Growth in real wages has been sluggish since 2013 in many advanced economies. For the average American worker they haven’t budged in 40 years.

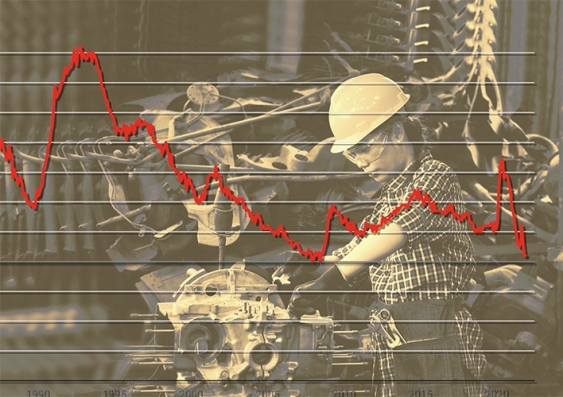

Annual growth in real wages

12-month growth in total hourly rates of pay excluding bonuses minus growth in consumer price index. ABS Wage Price Index, Consumer Price Index

There are many reasons for this. Labour-saving technologies are reducing demand for all sorts of human workers, from truck drivers and cashiers to junior lawyers and accountants. Globalisation and international trade have increased competition for less-skilled labour.

What economists call “skill-biased technical change” – new technologies requiring workers to have more skills – has increased wage inequality. The question is what to do about all of this.

The first-order policy response should be recognition that a tighter labour market than in the past is now needed to drive wages growth. That is, to get wages up we need to get unemployment down even further – and keep it there.

There is some resistance to this idea.

One argument is that Australia’s labour market isn’t all that competitive – that it’s full of all sorts of regulatory institutions such as the award system and enterprise bargaining that obscure or even break the relationship between unemployment and wages growth.

This has never been a persuasive argument. At most these institutions mean there will be lags in adjustment – with the Fair Work Commission reviewing awards once a year and enterprise agreements typically negotiated every three years.

Yet even these lags are less important than they used to be, now the percentage of private-sector workers covered by enterprise agreements is just 10.9 per cent compared with nearly a quarter in 2010.

The reality is that the majority of Australian workers have their pay determined by market forces, mediated by individual agreements. Supply and demand in the labour market is the key determinant of wage outcomes.

Understanding this helps frame what governments can and can’t do about wages.

They certainly can enact policies that drive unemployment down and hence wages up. On this count the Morrison government gets high marks and deserves due credit.

Read more: Vital Signs: wages growth desultory, unemployment stunning

They can also help provide workers with better skills, which lead to higher wages. One of the central lessons from economics is that people basically get paid for their skills.

Australia’s major political parties could do a much better job of formulating a comprehensive education and training policy.

Apprenticeship schemes are tinkering.

On the Labor side, announcing a few new apprenticeships is fine but really just tinkering. On the Liberal side, whining about postmodernism isn’t going to provide students with more human capital.

Governments could also encourage schemes to give workers a stake in the profits of the enterprises they work for – through employee share ownership or worker ownership schemes. Rosalind Dixon and I have proposed a “shadow equity” scheme as one way to implement this.

What governments can’t do is turn back the tide of globalisation and pretend automation won’t continue to replace or reduce demand for human labour.

It is futile, for example, to seek to resurrect Australia’s car manufacturing industry. Sure, let’s talk about developing new manufacturing industries, such as in battery technology, but a 1970s-style industry policy won’t bring back the jobs.

To get wages growth moving again we need lower unemployment, and to ensure it stays low. That won’t happen effectively by just mandating higher wages. It will happen by ensuring workers have the skills the market values, and by keeping macroeconomic policy settings tuned for low unemployment.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.