It's time to rethink Australia's fire management strategies

In this era of mega-fires, diverse strategies are urgently needed so we can safely live with fire.

In this era of mega-fires, diverse strategies are urgently needed so we can safely live with fire.

The current wet conditions delivered by La Niña, opens in a new window may have caused widespread flooding, but they’ve also provided a reprieve from the threat of bushfires in southeastern Australia. This is an ideal time to consider how we prepare for the next bushfire season.

Dry conditions will eventually return, as will fire. So, two years on from the catastrophic Black Summer fires, is Australia better equipped for a future of extreme fire seasons?

In our recent synthesis, opens in a new window on the Black Summer fires, we argue climate change is exceeding the capacity of our ecological and social systems to adapt. The paper is based on a series of reports, opens in a new window we, and other experts from the NSW Bushfire Risk Management Research Hub, were commissioned to produce for the NSW government’s bushfire inquiry.

Fire management in Australia has reached a crossroads, and “business as usual” won’t cut it. In this era of mega-fires, diverse strategies are urgently needed so we can safely live with fire.

In the age of mega fires, new strategies are needed. Photo: David Mariuz.

Various government inquiries following the Black Summer fires of 2019-20 produced wide-ranging recommendations for how to prepare and respond to bushfires. Similar inquiries have been held since 1939 after previous bushfires.

Typically, these inquiries, opens in a new window led to major changes to policy and funding. But almost universally, this was followed by a gradual complacency and failure to put policies into practice.

If any fire season can provide the catalyst for sustained changes to fire management, it is Black Summer. So, what have we learnt from that disaster and are we now better prepared?

To answer the first question, we turn to our analyses, opens in a new window for the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, opens in a new window.

Following the Black Summer fires, debate emerged about whether hazard reduction burning by fire authorities ahead of the fire season had been sufficient, or whether excessive “fuel loads” – such as dead leaves, bark and shrubs – had been allowed to accumulate.

We found no evidence the fires were driven by above-average fuel loads stemming from a lack of planned burning. In fact, hazard reduction burns conducted in the years leading up to the Black Summer fires effectively reduced the probability of high severity fire, and reduced the number of houses destroyed by fire.

Prescribed burning reduced the numbers of homes affected by fire. Photo: James Gourley/AAP.

Instead, we found the fires were primarily driven by record-breaking fuel dryness and extreme weather conditions. These conditions were due to natural climate variability, but made worse by climate change, opens in a new window. Most fires were sparked by lightning, and very few were thought to be the result of arson.

These extreme weather conditions meant the effectiveness of prescribed burns was reduced – particularly when an area had not burned for more than five years.

All this means that hazard reduction burning in NSW is generally effective, however in the face of worsening climate change new policy responses are needed.

As the Black Summer fires raged, loss of life and property most commonly occurred in regional areas while metropolitan areas were heavily affected by smoke. Smoke exposure from the disaster led to an estimated 429 deaths, opens in a new window.

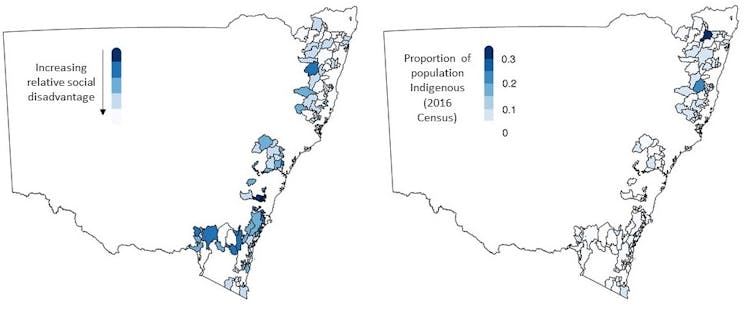

Socially disadvantaged and Indigenous populations were disproportionately affected by the fires, including by loss of income, homes and infrastructure, as well as emotional trauma, opens in a new window. Our analyses, opens in a new window found 38% of fire-affected areas were among the most disadvantaged, while just 10% were among the least disadvantaged.

We also found some areas with relatively large Indigenous populations, opens in a new window were fire-affected. For example, four fire-affected areas had Indigenous populations greater than 20% including the Grafton, Eurobodalla Hinterland, Armidale and Kempsey regions.

Demographic characteristics of fire-affected communities in NSW. Image: https://doi.org/10.3390/fire4040097

The Black Summer fires burnt an unprecedentedly large area, opens in a new window – half of all wet sclerophyll forests and over a third of rainforest vegetation types in NSW, opens in a new window.

Importantly, for 257 plant species, opens in a new window, the historical intervals between fires across their range were likely too short to allow effective regeneration. Similarly, many vegetation communities were left vulnerable to too-frequent fire, which may result in biodiversity decline, particularly as the climate changes.

Not all plant species can regenerate after too-frequent fire. Photo: Darren England/AAP.

So following Black Summer, how do we ensure Australia is better equipped for a future of extreme fire seasons?

As a first step, we must act on both the knowledge gained from government inquiries into the disaster, and the recommendations handed down. Importantly, long-term funding commitments are required to support bushfire management, research and innovation.

Governments have already increased investment in fire-suppression resources such as water-bombing aircraft, opens in a new window. There’s also been increased investment in fire management such as improving fire trails, opens in a new window and employing additional hazard reduction crews, as well as new allocations, opens in a new window for research funding.

But alongside this, we also need investment in community-led solutions and involvement in bushfire planning and operations. This includes strong engagement between fire authorities and residents in developing strategies for hazard reduction burning, and providing greater support for people to manage fuels on private land. Support should also be available to people who decide to relocate away from high bushfire risk areas.

The Black Summer fires led to significant interest in a revival of Indigenous cultural burning, opens in a new window – a practice that brings multiple benefits to people and environment. However, non-Indigenous land managers should not treat cultural burning as simply another hazard reduction technique, but part of a broader practice of Aboriginal-led cultural land management.

Indigenous burning is part of a broader practice of Aboriginal-led land management. Photo: Josh Whittaker.

This requires structural and procedural changes in non-Indigenous land management, as well as secure, adequate and ongoing funding opportunities. Greater engagement and partnership with Aboriginal communities at all levels of fire and land management is also needed.

Under climate change, living with fire will require a multitude of new solutions and approaches. If we want to be prepared for the next major fire season, we must keep planning and investing in fire management and research – even during wet years such as this one.

Ross Bradstock, Owen Price, David Bowman, Vanessa Cavanagh, David Keith, Matthias Boer, Hamish Clarke, Trent Penman, Josh Whittaker and many others contributed to the research upon which this article is based.

Rachael Helene Nolan, opens in a new window, Senior research fellow, Western Sydney University, opens in a new window; Grant Williamson, opens in a new window, Research Fellow in Environmental Science, University of Tasmania, opens in a new window; Katharine Haynes, opens in a new window, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, University of Wollongong, opens in a new window, and Mark Ooi, opens in a new window, Senior Research Fellow, UNSW, opens in a new window

This article is republished from The Conversation, opens in a new window under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, opens in a new window.