For nearly two years, Western Australia Premier Mark McGowan has sealed his state off from the rest of the world to pursue a hugely popular zero-COVID strategy.

Now the state is inching closer to reopening its borders to the world in early February, when 90% of the adult population is hopefully double-vaccinated.

The pandemic has tested the strength of the federation in many ways, but no state or territory has sealed itself off from the rest of the country as WA has.

McGowan’s strong stance on borders has reminded many of the long streak of separateness that has defined WA throughout history and placed it at odds with its eastern neighbours.

The distance from its sister states (and, before federation, sister colonies) helped make WA a late and somewhat reluctant member of the Commonwealth of Australia. This feeling of separateness remains today, although formal secession, once a dream of WA residents, is still a fantasy.

Four secessionist delegates holding the proposed flag for Western Australia in 1934. State Library of WA

Reluctance, then acceptance, of federation

By the 1890s, the campaign to unite the Australian colonies was gaining momentum. A depression in the eastern colonies bolstered the argument that all Australians would benefit from a common market.

Western Australians were far from convinced. The discovery of gold had led to a rapid growth of WA’s population and wealth. Western Australians worried their prosperity would be undermined by greater competition with the eastern states.

WA did not hold a referendum on federation in 1898 and 1899 when the other colonies did. But public sentiment soon shifted. The Gold Rush had sparked an influx of colonists from eastern Australia to the goldfields around Kalgoorlie, and pressure from these “tothersiders” saw the WA parliament reluctantly agree to a referendum.

More than half of the “yes” vote in the 1900 referendum came from easterners working in the goldfields.

Immediate attempts to break away

It took only five years, however, for the WA legislative assembly to tire of federation. In 1906, it passed a resolution in favour of WA’s withdrawal from the Commonwealth that did not lead anywhere.

The real impetus for an actual secession movement came during the Great Depression. Western Australians became increasingly resentful of protectionist tariffs imposed by the Commonwealth government on foreign imports. This protectionism seemed to benefit manufacturers in New South Wales and Victoria at the expense of primary producers like them.

In 1930, a Dominion League took wing in WA. The league was a pressure group whose aim was to make their state autonomous from Canberra. WA would instead be a “dominion” of the British Empire in the same way Australia and Canada were.

The Dominion League persuaded the Nationalist government led by James Mitchell to submit a referendum for secession to WA voters.

A meeting of the Dominion League for the secession movement, 1934. State Library of WA

The referendum took place on April 8 1933, at the same time as a state election. By a majority of two to one, Western Australians voted in favour of secession.

Voters also elected a Labor state government, and the premier, Philip Collier, was confronted by popular sentiment that was overwhelmingly in favour of separation from Canberra. He could not stop a loyal WA delegation petitioning the British parliament for secession in 1935.

The route the secessionist delegation favoured was an imperial act of parliament. This would amend the Australian Constitution, which had been enshrined in an act of the UK parliament.

The British parliament, however, rejected the state’s petition. It maintained that its own 1931 Statute of Westminster had given Australia dominion autonomy. So the only way WA could achieve independence would be with Canberra’s consent.

The Dominion League was bitterly disappointed, and got a modicum of revenge in 1937 by voting out the most prominent local advocate of federation, Senator George Pearce.

In the longer term, the federal parliament helped turn around the mood for separation in WA. It did this, in part, by promoting financial aid to WA and other smaller states through the Commonwealth Grants Commission.

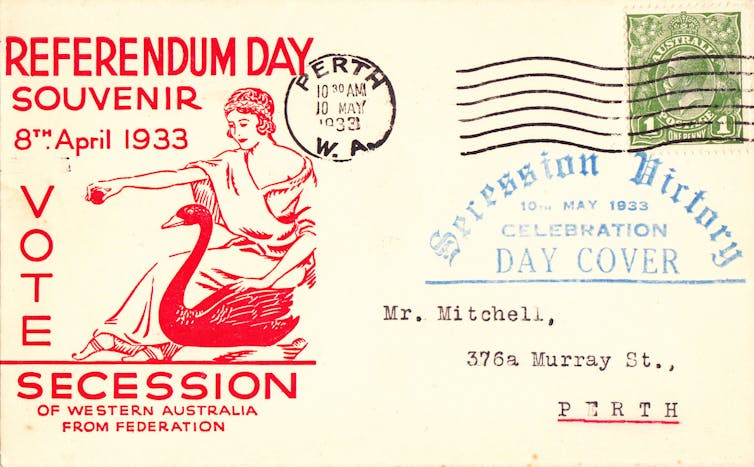

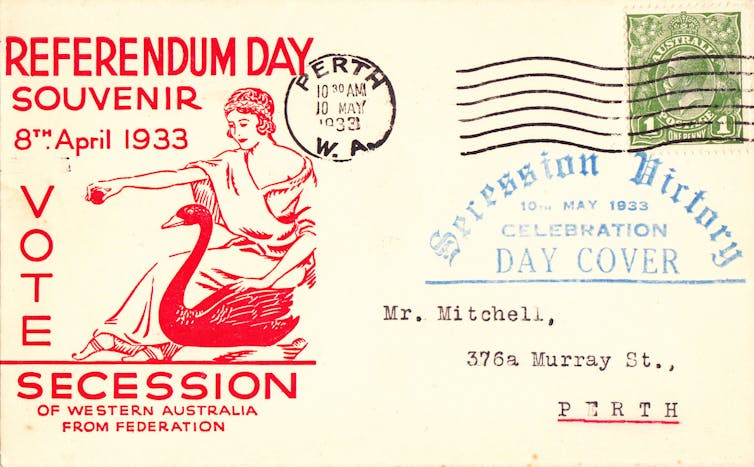

A souvenir envelope marking the celebration of the secession referendum in 1933. Wikimedia Commons

WA battles with Canberra over resources

From the 1930s onward, WA often clashed with Canberra and the eastern states.

One fight was over a 1938 decision of the Lyons government to stop the Japanese-led development of iron ore deposits at Yampi Sound, off Australia’s northwest. To do so, the Lyons government completely prohibited the sale of any Australian iron ore to foreign countries.

Throughout the 1950s, WA governments campaigned to modify the federal iron ore embargo. Finally, in 1959, the WA government led by Premier David Brand and Charles Court, the minister for industrial development, took unilateral action. It decided to advertise a public tender for the development of deposits at Mount Goldsworthy, a mining area that used Port Hedland as its outlet.

This started a chain of events that eventually persuaded the Menzies government to relax the embargo in 1960. The end of the embargo allowed the development of what would become Australia’s greatest export industry.

Then, in the 1960s and ‘70s, Canberra’s stipulation of minimum prices for WA mineral exports enraged the state government.

Court, WA premier from 1974-82, also campaigned against the Whitlam government’s plan to bypass WA by developing the oil and gas resources of the North West Shelf through a sovereign oil company.

In this context, a “Westralian” secession movement was revived with the financial backing of mining magnate Lang Hancock. It harked back to the rhetoric of the secessionist movement of the 1930s, but failed to translate an anti-Canberra sentiment into a concrete outcome like the 1933 secession plebiscite.

Echoes of the past

As recently as 2017, a group of WA Liberals revived a proposal to make the state an independent nation.

Since then, WA and the Commonwealth have frequently been at loggerheads, most recently over Clive Palmer’s challenge to WA’s closed borders during COVID (which the Morrison government backed for months until realising McGowan’s stance had overwhelming public support).

Today, distance and hard borders are being hailed as potential saviours of the west from the pandemic and the interminable lockdowns in the eastern states. After closing itself off for nearly two years, WA seems finally ready to reopen, although those long-harbored secessionist dreams will likely never die.

David Lee, Associate Professor of History, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.