Women, underemployment and gender inequality in the labour force

Latest underemployment and labour force figures underscore gender inequalities and suggest disadvantages are passing to future generations.

Latest underemployment and labour force figures underscore gender inequalities and suggest disadvantages are passing to future generations.

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), opens in a new window labour force figures, opens in a new window show underemployment has increased from 8.3 per cent in July to 9.3 per cent in August (and 16.6 per cent for 15-24-year-olds). While unemployment has fallen again, to 4.5 per cent in August compared to 4.6 per cent in July. For comparison, a year ago, the August unemployment rate was 6.8 per cent.

The number of hours being worked has decreased by 3.7 per cent (in seasonally adjusted terms) between July and August 2021. This follows falls of 1.8 per cent in June and 0.2 per cent in July – reflecting the increase in lockdowns and other restrictions during this period. So although unemployment has improved, hours worked has declined significantly, likely due to increased restrictions and lockdowns across several states.

But as well as reflecting the impacts of lockdowns, the ABS labour statistics highlight another pressing issue – the gender inequalities faced by women in the workforce.

The ABS defines an unemployed person as someone who, during a specified reference period, is not employed for one hour or more, is actively seeking work and is currently available for work. So if the unemployment rate declines, this means the number of unemployed people has reduced. This is what the most recent numbers showed, there are far fewer unemployed people than this time last year.

The ABS also measures underemployment, opens in a new window, which counts the number of people who are employed but not working full-time hours. Underutilisation figures capture both unemployment and underemployment. This means it measures the full extent to which available labour force resources are not being used in the economy.

When looking at the youth unemployment rate, which has risen from 10.2 per cent in July to 10.7 per cent over August, it’s clear the gap between youth unemployment, opens in a new window and the population's unemployment rate is still big.

However, this is relatively typical during an economic recovery, as youth unemployment is generally slower to recover, explains Professor Kristy Muir, CEO of the Centre for Social Impact (CSI) and a Professor of Social Policy in the Business School at UNSW Sydney. Younger people generally show higher levels of unemployment, also says Dr Evgenia Dechter, a Senior Lecturer at UNSW Business School.

She explains: “This is due to relatively low experience, skills, and, respectively, higher types of jobs. The younger groups are also more constrained in terms of hours (due to education activities), limiting the pool of jobs they can accept. This is not only Australian experience, but it is observed in many other economies worldwide.”

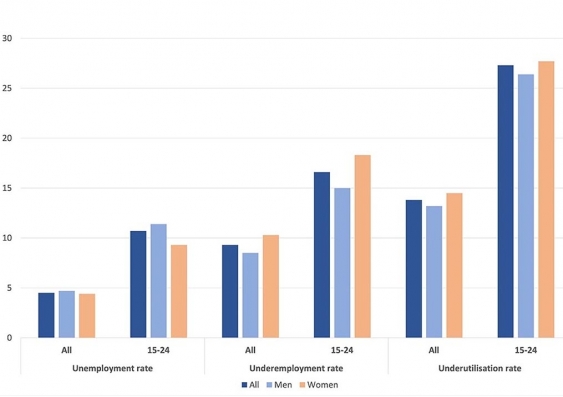

Labour Force Status Aug 2021 by age and gender (% seasonally adjusted)

The latest ABS labour force statistics offer a snapshot of gender and age inequity in Australia's workforce. Image: Supplied

Meanwhile, Australia’s underemployment figure has increased, this means that people who want to work more hours and can work more hours, aren’t getting them from their employers.

But what's really concerning is the persistent gender gap. Although underemployment has gone up for everybody, women are more likely to be underemployed (10.3 per cent) than men (8.5 per cent), explains Prof. Muir.

Underemployment is also higher for younger people than compared to the rest of the population, and looking at the numbers by gender, again it’s young women who are much more likely to be underemployed (18.3 per cent) than men (15.0 per cent), reiterates Prof. Muir.

“So, on the surface, unemployment looks like it’s getting better, and it is, in terms of the overall population statistics,” she says.

What's really concerning is the persistent gender gap. Although underemployment has gone up for everybody, women are more likely to be underemployed.

“But underemployment is worse, and women continue to fare worse than men. And then we also have the issue where you’ve got a much higher unemployment and underemployment rates for young people between 15 to 24-year-olds. Of concern is that over 1 in 4 (27.3 per cent) young people 15-24-years in the labour force are seeking some or more work, compared to more than 1 in 7 (13.8 per cent) across all ages.”

Why is this important?

“The figures reinforce inequality trends we saw before and during COVID-19. Economic uncertainty, opens in a new window has always affected young people more than the rest of the population and recovery usually has had a long tail. For women, gender inequity is not going away.

"We’ve witnessed women take up a higher proportion of caring and unpaid work, women losing jobs and hours because they are more likely to work in industries, opens in a new window affected by lockdowns and economic instability, and a widening of the gender pay gap, opens in a new window... these latest ABS labour statistics reinforce persistent and entrenched inequalities,” explains Prof. Muir.

Given businesses often reduce the hours of their workers as an early response to a labour market shock, it is not surprising the number of monthly hours worked in all jobs declined significantly. There have certainly been significant fluctuations over the past year. A sharp increase started in April 2020, followed by a sharp decline. By December 2021, the underemployment rate was back to pre-pandemic levels, explains Dr Dechter.

“The underemployment rate continued to decline until May-June 2021 and reached levels below the average of the last ten years,” says Dr Dechter.

However, she also says June-July underemployment figures were below their pre-pandemic levels and below average in the past five years (not including 2020 and 2021). In August we see the increasing effects of lockdowns and higher rates of underemployment, especially for men.

But does this mean the recent development in underemployment is a sign of crisis for working women?

See also: How COVID-19 has impacted working women

To better understand underemployment, it is essential to look back at historical data. “First, there is a slow increase in underemployment for men and women starting from the early 1990s. For example, for employed persons between 15-64 years old, the underemployment rate was 6.9 per cent in 1992 and 8.4 per cent in 2019. Underemployment is a persistent feature of the Australian labour market,” explains Dr Dechter.

“Second, the gender gap in underemployment is also persistent and remarkably constant, around 4 per cent in the early 1990s and about 2019. There is a decline in the underemployment gender gap in 2020-2021. Looking more closely at different age groups reveals the gender gap in underemployment varies with age. It is lowest for the 55-64 years old group and highest for the 35-44 years old.”

So regardless of COVID-19, the historical data suggests women have always been more likely to work part-time. While this is also the case for the younger group of 15-24 years olds, the gender gap in part-time employment increases with age.

In addition, with the increase in childcare demands, many women simply have no choice but to leave the labour force altogether.

The lack of affordable childcare in Australia is discouraging more women from staying in the workforce. Photo: Shutterstock

Working part-time at younger ages affects human capital accumulation and employment opportunities later in life, and the part-time work gender gap only increases with age.

“Part-time jobs are concentrated in low paid and less skilled occupations with little learning, low wage growth and low promotion opportunities. This is even more important when workplace dynamics change fast, and school acquired education becomes obsolete sooner,” explains Dr Dechter.

While the ABS labour figures show some improvements in female labour force participation, there is still a substantial gender gap in the participation rate and employment to population ratio.

“This is not uniform across age groups. If we look at the younger group, 15-24 years old, in the last 5-10 years, these rates are very similar and even higher for young women than for young men in recent years. This is not the case for the older age groups (the average gender gap in labour force participation is around 10 per cent in the five years before the pandemic), which suggests there are impediments for women to stay in the labour force,” says Dr Dechter.

Dr Dechter says that if women choose part-time employment because of constraints such as childcare costs, low wages, and no opportunities, this is incredibly concerning.

“A constrained choice to accept a part-time job affects not only the immediate quality of life but also prevents individuals from accumulating work experience, acquiring skills and being competitive in the labour market in later years,” she says.

“Moreover, part-time jobs are more likely to be casual jobs with limited access to benefits that a full-time job provides. As a result, we have relatively fewer women in high paying jobs, imposing further imbalances and unfavourable gender dynamics in the labour market.”

What can businesses and governments do to improve economic outcomes for women of all ages? Policies structured to improve labour market performance by providing equal access to quality education would be a step forward to achieving better outcomes.

“Gender wage gap implies that it is cheaper for women than for men to reduce working hours to care for children. Further reforms in the child-care system to provide affordable services to employed individuals are needed to break this cycle. Not only childcare for children under school age but also aftercare services for school-aged children. When the school day is 9am to 3pm, lack of after school care services basically imply no options for full-time employment for both parents,” explains Dr Dechter.

“More generally, as the number of women in high-ranked and visible roles is increasing, the more inspired will be younger generations to achieve labour market success. Therefore, businesses and organisations that take their role in shaping the society seriously should consider implementing policies that promote work-life balance."