Search for meaning of life fosters study of the brain

National Science Week: meet neuroscientist Dr Asheeta Prasad, whose career has been shaped by childhood questions.

National Science Week: meet neuroscientist Dr Asheeta Prasad, whose career has been shaped by childhood questions.

A typical childhood day in Fiji for Asheeta Prasad involved the beach, swimming, and picking guavas and star apples.

“Life was relaxing,” she says. “Conversations about science were not common.

“Instead, I remember being captivated by stories about myths and legends.”

But Dr Prasad also dreamed of being an astronaut.

“I remember looking up at the sky, wondering ‘how did that get there’,” she says.

“It was Diwali, the Festival of Lights, and there were lots of fireworks on, but the stars seemed more beautiful than the fireworks.”

In Fiji with her brothers Roneel (L) and Maveen (R). Photo: supplied.

The neuroscientist attended an all-girls Methodist school, moved to New Zealand when she was 10.

It was when she read an “interesting” newspaper article about Richard Faull, opens in a new window, a well known scientist who was collecting post-mortem brain tissue for a human brain bank that the seeds for her science career were sown.

“As a teenager, you try to make sense of life,” she says.

"What are we and why are we here - those were some of the underlying questions that always bothered me."

Her rationale was that if she could understand how organs functioned and their purpose, she might get close to answering how she could contribute towards something meaningful in the world.

"I always wanted to try to make an impact on people's lives," she says.

Dr Prasad enrolled in a Bachelor of Biomedical Science at Auckland University and transferred a year later to the University of Western Sydney.

Throughout her degree, she financially supported herself as a waitress, food delivery driver and a department store sales assistant.

She also worked in a research assistant role at the Kolling Institute at the Royal North Shore Hospital.

Asheeta Prasad spent a lot of time at the beach near Lautoka, Fiji as a child. Photo: Shutterstock.

“I wasn’t that interested in further education at that stage, I wanted to earn,” she says.

“It’s something I often hear from my honours students.”

After graduating, Dr Prasad returned to New Zealand to support her mother who had a health condition.

She worked at the New Zealand Blood Services, a diagnostic lab where she was involved in matching immune compatibility between organ donors and recipients. But within a year, she aspired for a career change.

“I had about $30,000 that I had saved and I had a choice: I could have invested it in an apartment, or in my future,” Dr Prasad says.

She followed her fascination with “DNA and genomics and how that is the blueprint of life” by beginning a Master of Molecular Biology at the University of Queensland.

“I spent my life savings so that I didn’t have to work and could focus on my studies,” she says.

“Academically, I did well and even got a Dean’s recommendation for my grades. For the first time I thought ‘I may be smart’.”

During her master’s research component, she had the opportunity to study at the Queensland Brain Institute, where she looked at how two different parts of the brain connect.

“In my bachelor degree, I thought I’d end up being a sales person or a science communicator, as I saw myself as more of a ‘people’ person…but once I saw that (wiring of the brain), that was it for me,” she says.

“I knew that I wanted to work with the brain, that master organ that controls everything we do, and neuroconnectivity was a key part of how the brain functions.

“I just thought ‘there is so much out there in the world I need to understand’ but it all comes down to people.

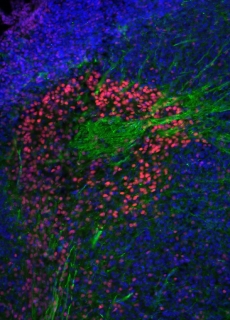

Dr Prasad discussed how scientific artwork could be derived from microscopic images of the human brain at the VIVID Festival in 2017. This one was the cover of Journal of Neuroscience. Image: Supplied.

“What makes us what we do, how we behave, why are we behaving so differently, why do some diseases and disorders affect some people and not others.”

After completing another research internship in India and inspired by the international student community she met in Brisbane, she looked for a suitable PhD program overseas.

“That’s the good thing about science, it is a universal language, you can study it anywhere,” she says.

While working at the Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, she enrolled in a PhD on neuroconnectivity at the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Her PhD looked at a molecular level at why the neurons of the chemical dopamine grow in complex networks throughout the brain, and why it forms complex connectivity.

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter for motivation, cognition and movement.

It is also an important neurotransmitter for motivator behaviour, not only for learning but also for maladaptive behaviour that can lead to drug addiction, as well as an important chemical for cognitive behaviour.

After the PhD, Dr Prasad married, had a child and after four years in The Netherlands, moved her family back to Sydney, where she joined UNSW’s School of Psychology to continue her love affair with research and to study the functions of dopamine in disease.

“All the behaviour that we do is learnt behaviour,” she says.

“For example with alcohol addiction, we don’t just get addicted, we learn about the association of alcohol, and its effect on our behaviour is formed in the memory and you keep on doing it.

“You can also learn not to drink.”

The research team (pictured) in Asheeta Prasad's lab are advancing knowledge of underlying dopamine disorders, specifically drug addiction and Parkinson’s disease. Photo: Supplied.

While Dr Prasad was working on why people relapse, she discovered a brain region called the subthalamic nucleus, opens in a new window which is importantly linked to motivator behaviours, but also movement disorders such as Parkinson’s Disease.

“I discovered something new, and I went with it,” she says.

Parkinson’s NSW funded her first research project looking into potential treatments for the disease.

She also received an Australian Research Council grant to research the neuro mechanisms of drug addiction.

The Asheeta Prasad Lab, opens in a new window is looking at three main areas: dopamine and its involvement in motivator behaviours, cognition and movement and how these behaviours become disrupted.

“Parkinson’s disease is marked by a loss of dopamine, so how does that happen, and how can we fix that?” she says.

“Dopamine is also important in motivator behaviour, but how does that become maladapted so that we get addicted behaviours?

“It’s also important for learning and memory, so how can it help people with dementia?”

Dr Prasad says before researchers can offer treatments, they need to understand “how things go wrong”.

“One of the reasons we don’t have therapies for drug addiction and Parkinson’s is because these disorders are not really understood,” she says.

“I do think I am making an impact at a more basic science level, by advancing knowledge of how the brain works.”

Dr Prasad skydiving near Wollongong. Photo: Supplied.

She says there aren’t many women of colour who are in universities in biomedical spaces.

“There aren’t very many…but I didn’t have any conception about what a scientist did, throughout my career, so I didn’t have any misconceptions about scientists, I just kept following the discoveries,” she says.

But there’s a misconception that her role is just lab work.

“My role involves doing experiments, writing grants, managing people and budgets, media engagement, communication, writing publications…scientists do a lot of different roles which include some aspects of accountancy and human resources.

“These are skills that we pick up along the way.”

In 2019, Dr Prasad visited her former primary school in Fiji to promote science. Photo: Supplied.

Outside of the lab, Dr Prasad enjoys boxing for fitness.

“It’s been a very helpful sport for me because it shows me about technique and science comes into it too,” she says.

“You don’t have to be a professor to make impactful contributions in science, it’s all about innovative thinking.

“You don’t have to throw a lot of punches to win, you just need impactful punches.

“Technique, strategy and innovation are key.”

Dr Prasad with her children Jiya (L) and Desmond. Photo: Supplied.

She enjoys thrill seeking sports such as sky diving, and spending time with her children.

Dr Prasad doesn’t think her career has been a textbook science story, “but it’s paid off and it’s a long-term investment”.

She says she never imagined she would be a research leader on brain and behaviour at a prestigious university.

“I could have married at 25, had an apartment, or continued to work at a diagnostic lab or as a research assistant,” she says.

“All of those were my alternatives. It’s been a progressive dream in the making.

“There were clear, decisive moments where rationale and the safe lane were set aside for adventure and excitement.”

She recommends that students “invest in yourself”.

“Your education is something no one can take from you.”