'It's time to walk together towards a referendum': Indigenous Law Centre

The Uluru Dialogue group based at UNSW Indigenous Law Centre says constitutional recognition cannot be dislocated from the idea of a Voice to Parliament.

The Uluru Dialogue group based at UNSW Indigenous Law Centre says constitutional recognition cannot be dislocated from the idea of a Voice to Parliament.

Almost four years after the issuing of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, key community leaders and legal scholars say there can be no more delay in moving towards a referendum.

“It’s time to take a Voice to Parliament to the Australian people, to start the work to hold a referendum,” Professor Megan Davis, UNSW Professor of Law and Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law, says.

“Now is the time to walk together and address the unfinished business of this nation.”

The poetic words of the Uluru Statement, which represent a “strategic roadmap to peace”, has spread across the country, Prof Davis says.

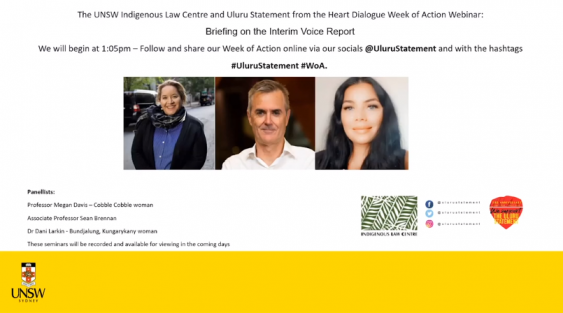

Professor Megan Davis at the Uluru Constitutional Convention in 2017. Photo: UNSW Indigenous Law Centre

Australians of all walks of life have “heard and accepted the Uluru Statement’s invitation, with support of a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament growing every day”.

Prof Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman and co-chair of the Uluru Dialogue – a group of First Nations and non-Indigenous community leaders, law scholars and advocates – based at the UNSW Indigenous Law Centre, says the government should recognise this growing grassroots support.

In 2020, the Australian Reconciliation Barometer found that 95% of the general community agreed it is important that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a say in matters that affect them.

The Barometer further detailed how “86% of the general community think it is important to establish a representative Indigenous body” and “81% of the general community think it is important to protect that body within the constitution”.

“The public wants to move towards a better Australia,” Prof Davis says.

“A place where the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are heard and are central to Australian life. Australians want a First Nations Voice to Parliament, protected by the constitution.

"It’s time for the government to commit to a referendum.”

Watch: UNSW Indigenous Law Centre briefing on the Interim Voice report. This first briefing examines the design options.

The recent Interim Report on the design of a Voice does not “foreclose or prevent holding a referendum” to enshrine a First Nations Voice to Parliament in the constitution.

The time is “now for Australians to show the government that they support a constitutionally protected Voice”, Prof Davis says.

This is despite the question of constitutional recognition explicitly made “out-of-scope” during the co-design Voice process lead by Professor Marcia Langton and Professor Tom Calma.

The Interim report avoids making a direct connection between the report and the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

“But that is where this process has come from,” Prof Davis says. “You cannot separate the idea of a Voice to Parliament and constitutional recognition.”

What has occurred since the Uluru Statement from the Heart?

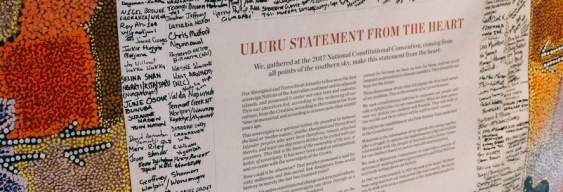

Photo: Indigenous Law Centre, Jimmy Widders Hunt.

As the wind swept around the base of Uluru, the Uluru Statement from the Heart was read for the first time. Its historic calls for Voice, Treaty and Truth, endorsed by 250 First Nations delegates – an unprecedented consensus and the result of over 13 regional dialogues that consulted 1200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – set out a “new path to a better future”.

In response to the Uluru Statement, a Joint Select Committee concluded there was only one option for constitutional recognition that was viable: a First Nations Voice to Parliament. It recommended that a co-design process be set-up to develop more detail for the design of a Voice.

After the work of this Joint Select Committee, the government decided it wanted more detail of what a Voice body would look like. It wanted more “meat on the bones for the idea of a Voice before it finalised a referendum question”.

The Liberal government also took a commitment to pursue constitutional recognition to the 2019 federal election. This included $7.3 million to develop a proposal to take to a referendum, and a budget allocation of $160 million to hold a referendum, held ‘once a model has been settled’.

In January 2021, the co-design group released an Interim Report for public consultation on the design options for the Voice. It is open for everyone to have their say. Submissions are open until 31 March 2021.

The Uluru Statement was explicit in its call for a First Nations Voice to Parliament to be “enshrined in the constitution”.

After years of pursuing symbolic recognition, a notion rejected by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates at Uluru and the preceding dialogues, a Voice to Parliament represents substantive constitutional recognition.

But what does constitutional enshrinement mean? And why is it so important?

Professor Gabrielle Appleby, a public law scholar based at UNSW Law, says constitutional enshrinement does not mean including all the details of Voice to Parliament in the Australian Constitution.

The constitutional entrenchment of a Voice to Parliament simply means the “constitutional protection of the existence and primary function of the Voice, not the detail”, she says.

Watch: UNSW Indigenous Law Centre briefing on the Interim Voice report. This second briefing examines the role of constitutional protection of a Voice to Parliament.

Instead, the detail – such as the number of members and how representatives are elected or chosen – “will be determined by legislation and can be changed and adapted to future circumstances”.

Critically, Prof Appleby says, an enshrined Voice to Parliament “is not a new constitutional ‘right’ that increases the power of judges, or a ‘third chamber’ of Parliament”.

Former High Court Justice Murray Gleeson has also supported the constitutional protection of a Voice to Parliament, saying that “[it] is consistent with the nature of the Constitution and the values that underpin it”.

If the government pursued a legislated Voice, that would also ignore a decade long process and the wishes of First Nations people, says Dr Dani Larkin.

Dr Larkin, a Bundjalung/Kungarykany woman and Deputy Director of the ILC, says a Voice to Parliament and constitutional recognition cannot be “framed as different ideas”.

“Constitutional enshrinement of a First Nations Voice is the only form of recognition that garnered the collective endorsement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

“Symbolic recognition has been rejected. The Uluru Statement makes that clear. Constitutional enshrinement is also the only means to protect a Voice from any future threat of abolition from successive governments,” Dr Larkin says.

Constitutional protection instead gives “the Voice stability, to have our voices heard and acted on while having the flexibility to adapt the design over time”.

Alongside this protection and stability, Prof Appleby says, a referendum on the question of Voice to Parliament will also impact the primacy of the First Nations Voice in its dealings with parliament and government.

The Uluru Statement was the culmination of 13 Regional Dialogues with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across Australia. Photo: Indigenous Law Centre

"A successful referendum will give the Voice public legitimacy and authority it needs to make sure the government and Parliament will take its advice seriously."

“By a popular vote at a referendum, the Australian people will give the Voice a legitimacy and primacy that cannot be achieved through legislation.”

It is concerning too, Professor Davis says, that the co-design committee members seem to be conflating the institutions of government and parliament.

“This is reflected in the report,” she says. “There have also been public comments that describe the difference between government and parliament as flimsy.

“That is a fundamental misunderstanding of the functions of each institution in terms of its representation and accountability.

“The First Nations at Uluru clearly understood the distinction. It’s important.”

The Interim report, developed by the co-design group picked by the government, contains the details of what the Voice would look like.

The report canvases two mechanisms: A Voice to Government and a Voice to Parliament.

Whilst it is important, Dr Larkin says, that specific feedback on design features is included in public submissions – including in how members are elected, and the interplay between regional and national Voices – submissions should highlight constitutional entrenchment of a Voice to Parliament and emphasise the support for holding a referendum on the issue.

In the National Indigenous Times, Dr Larkin writes: “They [the Interim report authors] have opened the door to submission on a constitutionally enshrined Voice.

"They have invited comparison because it is necessary to contemplate the effectiveness of their Voice proposal.”

***

After decades of work, advocacy, and community engagement, “Australians now have the opportunity to take the next steps towards a new relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”, says Prof Davis.

As the co-design process continues to establish the final model of a Voice, the public can “make a difference and make it now”.

“It is only the Australian people that have the power to unlock the Australian Constitution,” Prof Davis says.

“It’s also the public, the people, everyday Australians, that can lead governments to take the necessary steps to enact lasting change.”

Making submissions that include the support of constitutionally enshrined Voice, Prof Davis says, shows the Government that this is what the broader public want and support.

“We have had a decade long process, which eventually led to a moment where the Government asked First Nations people: 'What would constitutional recognition look like for you?'

“Through 13 Regional Dialogues that culminated at the Uluru Convention in 2017, a moment that produced the Uluru Statement from the Heart, we got that answer. We got a consensus.”

It's time, Prof Davis says, for the question to be put to the Australian people.

“It's beyond time.”

Read more information on the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

You can make submissions to the Interim Report here.

Watch the three briefings of the Interim Report by the Indigenous Law Centre.